General Relativity survives gruelling pulsar test - Einstein at least 99.95% right!

14th September 2006

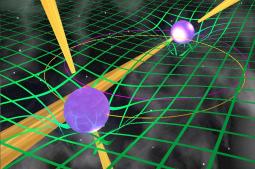

The image shows the two pulsars which orbit the common centre of mass in only 144 minutes. A number of relativistic effects are observed to high precision. These include the shrinkage of the orbits by 7mm/day due to the emission of gravitational waves and the "Shapiro delay" by which the pulse arrival times at the telescopes are delayed when the pulses travel through the curved space-time (indicated by the green grid) near the companion. Credit is Michael Kramer, Jodrell Bank Observatory. Click image for higher resolution image.

An international research team led by Prof. Michael Kramer of the University of Manchester's Jodrell Bank Observatory, UK, has used three years of observations of the "double pulsar", a unique pair of natural stellar clocks which they discovered in 2003, to prove that Einstein's theory of general relativity - the theory of gravity that displaced Newton's - is correct to within a staggering 0.05%. Their results are published on the 14th September in the journal Science and are based on measurements of an effect called the Shapiro Delay.

The double pulsar system, PSR J0737-3039A and B, is 2000 light-years away in the direction of the constellation Puppis. It consists of two massive, highly compact neutron stars, each weighing more than our own Sun but only about 20 km across, orbiting each other every 2.4 hours at speeds of a million kilometres per hour. Separated by a distance of just a million kilometres, both neutron stars emit lighthouse-like beams of radio waves that are seen as radio "pulses" every time the beams sweep past the Earth. It is the only known system of two detectable radio pulsars orbiting each other. Due to the large masses of the system, they provide an ideal opportunity to test aspects of General Relativity:

- Gravitational redshift: the time dilation causes the pulse rate from one pulsar to slow when near to the other, and vice versa.

- Shapiro delay: The pulses from one pulsar when passing close to the other are delayed by the curvature of space-time. Observations provide two tests of General Relativity using different parameters.

- Gravitational radiation and orbital decay: The two co-rotating neutron stars lose energy due to the radiation of gravitational waves. This results in a gradual spiralling in of the two stars towards each other until they will eventually coalesce into one body.

By precisely measuring the variations in pulse arrival times using three of the world's largest radio telescopes, the Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank, the Parkes radio-telescope in Australia, and the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, USA, the researchers found the movement of the stars to exactly follow Einstein's predictions. "This is the most stringent test ever made of General Relativity in the presence of very strong gravitational fields -- only black holes show stronger gravitational effects, but they are obviously much more difficult to observe", says Kramer.

Since both pulsars are visible as radio emitting clocks of exceptional accuracy, it is possible to measure their distances from their common centre of gravity. "As in a balanced see-saw, the heavier pulsar is closer to the centre of mass, or pivot point, than the lighter one and so allows us to calculate the ratio of the two masses", explains co-author Ingrid Stairs, an assistant professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. "What's important is that this mass ratio is independent of the theory of gravity, and so tightens the constraints on General Relativity and any alternative gravitational theories." adds Maura McLaughlin, an assistant professor at West Virginia University in Morgantown, WV, USA.

Though all the independent tests available in the double pulsar system agree with Einstein's theory, the one that gives the most precise result is the time delay, known as the Shapiro Delay, which the signals suffer as they pass through the curved space-time surrounding the two neutron stars. It is close to 90 millionths of a second and the ratio of the observed and predicted values is 1.0001 +/- 0.0005 - a precision of 0.05%.

A number of other relativistic effects predicted by Einstein can also be observed. "We see that, due to its mass, the fabric of space-time around a pulsar is curved. We also see that the pulsar clock runs slower when it is deeper in the gravitational field of its massive companion, an effect known as "time dilation".

A key result of the observations is that the pulsar's separation is seen to be shrinking by 7mm/day. Einstein's theory predicts that the double pulsar system should be emitting gravitational waves - ripples in space-time that spread out across the Universe at the speed of light. "These waves have yet to be directly detected ", points out team member Prof. Dick Manchester from the Australia Telescope National Facility, "but, as a result, the double pulsar system should lose energy causing the two neutron stars to spiral in towards each other by precisely the amount that we have observed - thus our observations give an indirect proof of the existence of gravitational waves."

Michael Kramer concludes; "The double pulsar is really quite an amazing system. It not only tells us a lot about general relativity, but it is a superb probe of the extreme physics of super-dense matter and strong magnetic fields but is also helping us to understand the complex mechanisms that generate the pulsar's radio beacons." He concludes; "We have only just begun to exploit its potential!"

Contacts:

Professor Michael Kramer

University of Manchester

+44 1477 571321

mkramer@jb.man.ac.uk

Professor Andrew Lyne

University of Manchester

+44 1477 571321

agl@jb.man.ac.uk

Julia Maddock

PPARC Press Office

Tel +44 1793 442094

Email: julia.maddock@pparc.ac.uk

International contacts:

Dr. Ingrid Stairs

University of British Columbia

Tel +1 604 822 6796

Email: stairs@astro.ubc.ca

The full team consists of:

Prof. Michael Kramer, and Prof. Andrew Lyne, JBO

Dr. Ingrid Stairs and Mr. Robert Ferdman, UBC

Drs. Richard Manchester, John Sarkissian, George Hobbs, and John

Reynolds, ATNF

Drs. Maura McLaughlin, and Duncan Lorimer, West Virginia University

Drs. Marta Burgay, Andrea Possenti and Nichi D'Amico, INAF-OAC

Dr. Paulo Freire, Arecibo Observatory

Dr. Fernando Camilo, Columbia University.

"Tests of general relativity from timing the double pulsar"

To be published in the journal Science, available from Sept. 14th on Science Express.

Click to download the abstract or full reprint of the paper

Background Information

A pulsar is a neutron star, which is the collapsed core of a massive star that has ended its life in a supernova explosion. Weighing more than our Sun, yet only 20 kilometres across, these incredibly dense objects produce a beam of radio waves which sweeps around the sky like a lighthouse, often hundreds of times a second. Radio telescopes receive a regular train of pulses as the beam repeatedly crosses the Earth so the object is observed as a pulsating radio signal. Further information on pulsars can be found on the Jodrell Bank Observatory Pulsar Group pages.

The Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council (PPARC) is the UK's strategic science investment agency. It funds research, education and public understanding in four areas of science - particle physics, astronomy, cosmology and space science.

PPARC is government funded and provides research grants and studentships to scientists in British universities, gives researchers access to world-class facilities and funds the UK membership of international bodies such as the European Laboratory for Particle Physics (CERN), and the European Space Agency. It also contributes money for the UK telescopes overseas on La Palma, Hawaii, Australia and in Chile, the UK Astronomy Technology Centre at the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh and the MERLIN/VLBI National Facility, which includes the Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank Observatory.

PPARC's Public Understanding of Science and Technology Awards Scheme funds both small local projects and national initiatives aimed at improving public understanding of its areas of science.