The Night Sky March 2009

Compiled by Ian Morison

This page, updated monthly, will let you know some of the things that you can look out for in the night sky. It lists the phases of the Moon, where you will see the naked-eye planets and describes some of the prominent constellations in the night sky during the month.

Image of the Month

The Carina Nebula

Image: European Southern Observatory

In the band of the milky way not far from the Southern Cross lies the constellation of Carina. Within it lies a jewel of the southern sky - the Carina nebula. This is a giant star formation region like the Orion Nebula but lies 5 times further away at a distance of 7500 light years. Like Orion, it is visible to the naked eye and spectacular in a small telescope. This spectactular image was taken by a 2.2m telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile and reveals the details of the glowing filaments of interstellar gas mingled with dar dust clouds. Like Orion it is a stellar nursary and home to some extremely massive stars including the star Eta Carine which is over 100 times the mass of out Sun.

Highlights of the Month

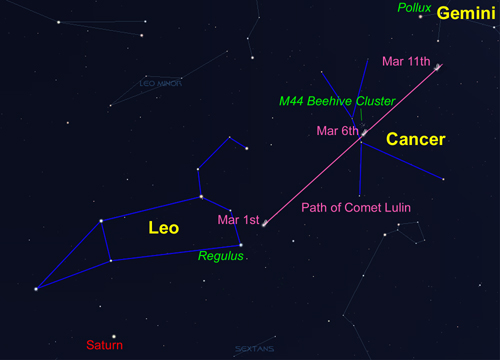

March 1st to 11th: Observe Comet Lulin passing from Leo into Cancer.

Comet Lulin is now moving away from the Earth and thus decoming less bright but may still be just visible to the unaided eye. On the first of March it lies to the upper right of the star Regulus in Leo and as the days progress moves up to the right into Cancer where is passes just below the Beehive Cluster, M44, on the 6th March. Sadly, a gibbous Moon will make it harder to spot and binoculars will almost certainly be necessary. At its closest approach to Earth on the 23rd February it was expected to have reached magnitude 5 but will now be falling in brightness. Due to the direction form which we onserve it, the dust tail appears to point towards the Sun - a so called antitail - with the fainter ion or gas tail pointing ( as always) away form the Sun. Colour photographs show that the coma has a distinct greenish colour caused by the flourescence of CN and C2 molecules.

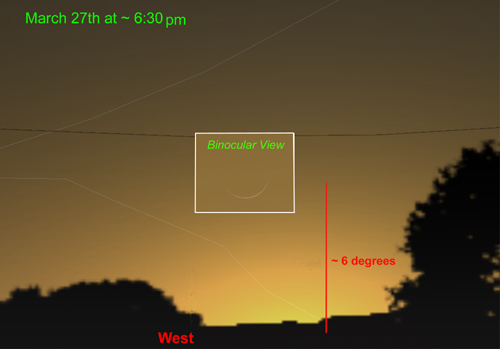

March 27th: Use Binoculars to spot a very thin crescent Moon

At this time of the year the ecliptic - where one will find the planets - rises steeply above the western horizon in the evening. This is why Venus has appeared so high in the sky. This also gives us a chance to spot a very thin crescent Moon - just 27 hours after new-moon - low in the western sky about 40 minutes after sunset. You will almost certainly need a pair of binoculars and so do not look until after the Sun has set for fear of damaging your eyes. Only 1.6% of the Moon's face will be illuminated. It should hang in the sky at an azimuth of 284 degrees - just north of west. The image below was taken of the old moon (and hence imaged at dawn) just 36 hours before new moon, so somewhat fuller that it will appear on the 27th March.

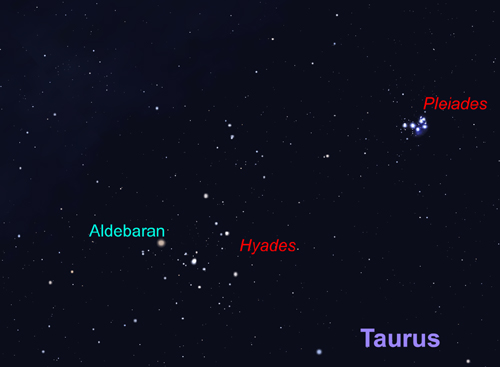

March: Have a good look at the Hyades and Pleiades Clusters.

The two nearest open clusters to us - the Hyades and Pleiades Clusters are high in the sky after sunset so march is still a good month to observe them. The Pleiades Cluster is one of the youngest open clusters and is dominated by blue stars that have been formed within the last 100 million years. None have yet evolved into red giant stars - so helping to define its age. It appears to be passing through a cloud of dust which is scattering the blue light form the stars forming so called "reflection nebulae" around the brighter stars of the cluster. The Pleiades are a lovely sight in high power binoculars or a short focal length telescope. The closer Hyades Cluster is older and does contain some evolved stars. The stars Aldebaran, the eye of the Bull, lies about halfway between the Hyades Cluster and the Earth so is not part of it.

Observe the International Space Station

The International Space Station and Jules Verne passing behind the Lovell Telescope on April 1st 2008.

Image by Andrew Greenwood

Use the link below to find when the space station will be visible in the next few days. In general, the space station can be seen either in the hour or so before dawn or the hour or so after sunset - this is because it is dark and yet the Sun is not too far below the horizon so that it can light up the space station. As the orbit only just gets up the the latitude of the UK it will usually be seen to the south, and is only visible for a minute or so at each sighting. Note that as it is in low-earth orbit the sighting details vary quite considerably across the UK. The NASA website linked to below gives details for several cities in the UK. (Across the world too for foreign visitors to this web page.)

Note: I observed the ISS three times in the last week or so of July and was amazed as to how bright it has become.

Find details of sighting possibilities from your location from: Location Index

See where the space station is now: Current Position

The Moon

The Moon at 3rd Quarter. Image, by Ian Morison, taken with a 150mm Maksutov-Newtonian and Canon G7.

Just below the crator Plato seen near the top of the image is the mountain "Mons Piton". It casts a long shadow across the maria from which one can calculate its height - about 6800ft or 2250m.

| new | first quarter | full moon | last quarter |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 26th | March 4th | March 11th | March 18th |

Some Lunar Images by Ian Morison, Jodrell Bank Observatory: Lunar Images

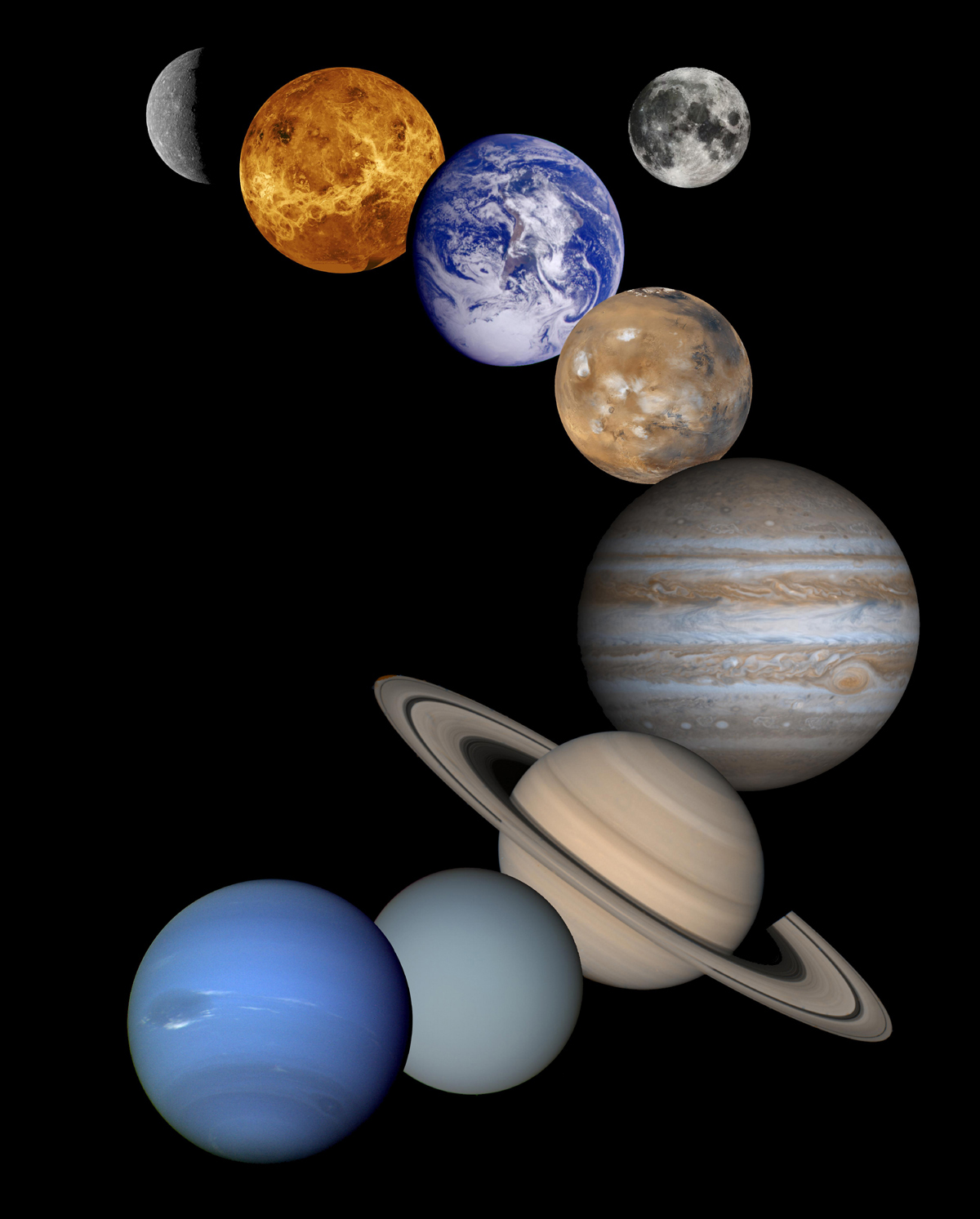

The Planets

Jupiter

Jupiter is not easily visible this month as, though its seperation from the Sun is increasing in the pre-dawn sky, its elevation is still very low as the ecliptic is at a shallow angle to the horizon in springtime. By the very end of March it will be 45 degrees from the Sun and, at magnitude -2.1, might just be glimpsed very low in the south-east just before dawn. It will only be ~7 degrees above the horizon so binoculars may well be needed. It will lie close the the waning thin crescent Moon on the 22nd (to the left of the Moon) and 23rd (to its right). Better wait a month or so!Saturn

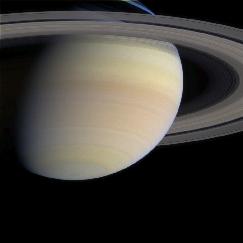

Saturn is now the best placed planet in the sky - and you no longer need to wait up too late at night to observe it! It rises in the east at around 7:30pm at the beginning of the month and atsun-set by month's end. Lying below the outline of Leo, it has a magnitude of ~0.5 throughout the month. This is significantly less than it often appears as the rings are now, with a tilt of about 2.8 degrees, almost edge on! In September this year they will become edge on to us and become invisible!

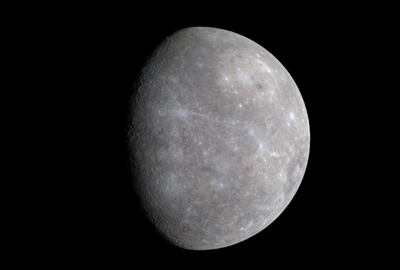

Mercury

Mercury: is moving away from us this month and will be on the far side of the Sun (superior conjunction) on the 31st March. There is just a chance to spot it at the very beginning of the month before dawn. It will be very low (~2 degrees) above the horizon and seen down to the lower left of Jupiter but, to be honest, its probably not worth it.

Mars

Mars is still close in angle to the Sun (just 21 degrees as March begins) so will be very hard to spot in the pre-dawn sky having a magnitude of 1.2. By the end of the month the angular seperation has increased to 28 degrees which helps, but as the ecliptic makes such a small angle to the horizon that Mars will be just 4 degrees above the horizon as the Sun rises. We will have to wait a month or so until it will be seen easily in the pre-dawn sky.

Venus

Venus has been dominating the western sky after sunset for the last few weeks and can still, as March begins, be seen high in the west after sunset shining at magnitude -4.5 so can hardly be missed! During the month, Venus gradually gets closer in angle to the Sun. As the month progresses its brightness drops slightly. As the month progresses and Venus comes between us and the Sun, the angular size increases, but the percentage that is illuminated will drop. These two effects tend to cancel out in the way they affect its apparent brightness which is why the brightness remains almost constant for several months. Venus will be seen lower in the sky week by week and by the 20th will start to become hard to spot in the glare of the Sun. It will lie between us and the Sun (called inferior conjunction) on March 27th so will be invisible for some time before reappearing in the pre-dawn sky around the 5th of April.

Find more planetary images and details about the Solar System: The Solar System

The Stars

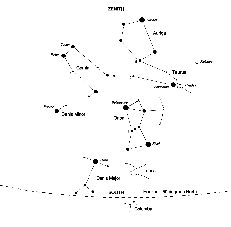

The Early Evening March Sky

This map shows the constellations seen in the south during the early evening. The brilliant constellation of Orion is seen in the south. Moving up and to the right - following the line of the three stars of Orion's belt - brings one to Taurus; the head of the bull being outlined by the V-shaped cluster called the Hyades with its eye delineated by the orange red star Aldebaran. Further up to the right lies the Pleaides Cluster. Towards the zenith from Taurus lies the constellation Auriga, whose brightest star Capella will be nearly overhead. To the upper left of Orion lie the heavenly twins, or Gemini, their heads indicated by the two bright stars Castor and Pollux. Down to the lower left of Orion lies the brightest star in the northern sky, Sirius, in the consteallation Canis Major. Up and to the left of Sirius is Procyon in Canis Minor. Rising in the East is the constellation of Leo, the Lion, with the planet Saturn up and to the right of Regulus its brightest star. Continuing in this direction towards Gemini is the faint constellation of Cancer with its open cluster Praesepe (also called the Beehive Cluster),the 44th object in Messier's catalogue. On a dark night it is a nice object to observe with binoculars. There is also information about the constellation Ursa Major,seen in the north, in the constellation details below.

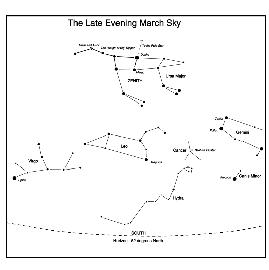

The Late Evening March Sky

This map shows the constellations seen in the south around midnight.

The constellation Gemini is now setting towards the south-west and Leo holds pride (sic) of place in the south with its bright star Regulus. Between Gemini and Leo lies Cancer. It is well worth observing with binoculars to see the Beehive Cluster at its heart. Below Gemini is the tiny constellation Canis Minor whose only bright star is Procyon. Rising in the south-east is the constellation Virgo whose brightest star is Spica. Though Virgo has few bright stars it is in the direction of of a great cluster of galaxies - the Virgo Cluster - which lies at the centre of the supercluster of which our local group of galaxies is an outlying member.

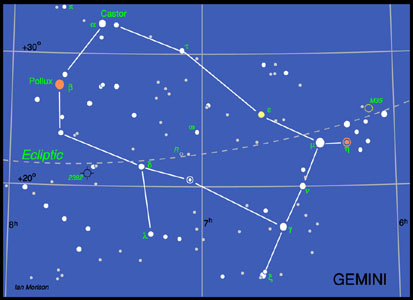

The constellation Gemini

Gemini - The Twins - lies up and to the left of Orion and is in the south-west during early evenings this month. It contains two bright stars Castor and Pollux of 1.9 and 1.1 magnitudes respectivly. Castor is a close double having a separation of ~ 3.6 arc seconds making it a fine test of the quality of a small telescope - providing the atmospheric seeing is good! In fact the Castor system has 6 stars - each of the two seen in the telescope is a double star, and there is a third, 9th magnitude, companion star 73 arcseconds away which is alos a double star! Pollux is a red giant star of spectral class K0. The planet Pluto was discovered close to delta Geminorum by Clyde Tombaugh in 1930. The variable star shown to the lower right of delta Geminorum is a Cepheid variable, changing its brightness from 3.6 to 4.2 magnitudes with a period of 10.15 days

M35 and NGC 2158

This wonderful image was taken by Fritz Benedict and David Chappell using a 30" telescope at McDonal Observatory. Randy Whited combined the three colour CCD images to make the picture

M35 is an open star cluster comprising several hundred stars around a hundred of which are brighter than magnitude 13 and so will be seen under dark skies with a relativly small telescope. It is easily spotted with binoculars close to the "foot" of the upper right twin. A small telescope at low power using a wide field eyepiece will show it at its best. Those using larger telescopes - say 8 to 10 inches - will spot a smaller compact cluster NGC 2158 close by. NGC 2158 is four times more distant that M35 and ten times older, so the hotter blue stars will have reached the end of their lives leaving only the longer-lived yellow stars like our Sun to dominate its light.

To the lower right of the constellation lies the Planetary Nebula NGC2392. As the Hubble Space Telescope image shows, it resembles a head surrounded by the fur collar of a parka hood - hence its other name The Eskimo Nebula. The white dwarf remnant is seen at the centre of the "head". The Nebula was discovered by William Herschel in 1787. It lies about 5000 light years away from us.

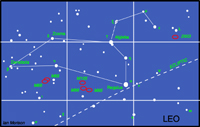

The constellation Leo

The constellation Leo is now in the south-eastern sky in the evening. One of the few constellations that genuinely resembles its name, it looks likes one of the Lions in Trafalger Square, with its main and head forming an arc (called the Sickle) to the upper right, with Regulus in the position of its right knee. Regulus is a blue-white star, five times bigger than the sun at a distance of 90 light years. It shines at magnitude 1.4. Algieba, which forms the base of the neck, is the second brightest star in Leo at magnitude 1.9. With a telescope it resolves into one of the most magnificent double stars in the sky - a pair of golden yellow stars! They orbit their common centre of gravity every 600 years. This lovely pair of orange giants are 170 light years away.

Leo also hosts two pairs of Messier galaxies which lie beneath its belly. The first pair lie about 9 degrees to the west of Regulus and comprise M95 (to the east) and M96. They are almost exactly at the same declination as Regulus so, using an equatorial mount, centre on Regulus, lock the declination axis and sweep towards the west 9 degrees. They are both close to 9th magnitude and may bee seen together with a telescope at low power or individually at higher powers. M65 is a type Sa spiral lying at a distance of 35 millin klight years and M66, considerably bigger than M65, is of type Sb. Type Sa spirals have large nuclei and very tightly wound spiral arms whilst as one moves through type Sb to Sc, the nucleus becomes smaller and the arms more open.

The second pair of galaxies, M95 and M96, lie a further 7 degrees to the west between the stars Upsilon and Iota Leonis. M95 is a barred spiral of type SBb. It lies at a distance of 38 million light years and is magnitude 9.7. M96, a type Sa galaxy, is slightly further away at 41 million light years, but a little brighter with a magnitude of 9.2. Both are members of the Leo I group of galaxies and are visible together with a telescope at low power.

There is a further ~9th magnitude galaxy in Leo which, surprisingly, is in neither the Messier or Caldwell catalogues. It lies a little below lambda Leonis and was discovered by William Herschel. No 2903 in the New General Catalogue, it is a beautiful type Sb galaxy which is seen at somewhat of an oblique angle. It lies at a distance of 20.5 million light years.

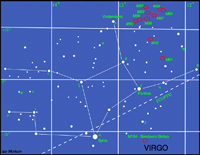

The constellation Virgo

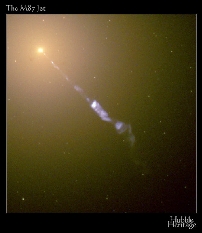

Virgo, rising in the east in late evening this month, is not one of the most prominent constellations, containing only one bright star, Spica, but is one of the largest and is very rewarding for those with "rich field" telescopes capable of seeing the many galaxies that lie within its boundaries. Spica is, in fact, an exceedingly close double star with the two B type stars orbiting each other every 4 days. Their total luminosity is 2000 times that of our Sun. In the upper right hand quadrant of Virgo lies the centre of the Virgo Cluster of galaxies. There are 13 galaxies in the Messier catalogue in this region, all of which can be seen with a small telescope. The brightest is the giant elliptical galaxy, M87, with a jet extending from its centre where there is almost certainly a massive black hole into which dust and gas are falling. This releases great amounts of energy which powers particles to reach speeds close to the speed of light forming the jet we see. M87 is also called VIRGO A as it is a very strong radio source.

Below Porrima and to the right of Spica lies M104, an 8th magnitude spiral galaxy about 30 million light years away from us. Its spiral arms are edge on to us so in a small telescope it appears as an elliptical galaxy. It is also known as the Sombrero Galaxy as it looks like a wide brimmed hat in long exposure photographs.

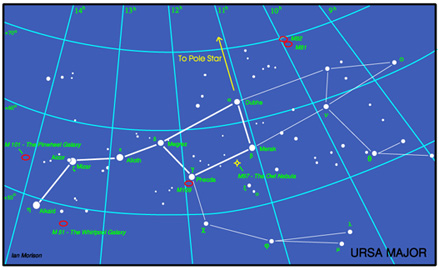

The constellation Ursa Major

The stars of the Plough, shown linked by the thicker lines in the chart above, form one of the most recognised star patterns in the sky. Also called the Big Dipper, after the soup ladles used by farmer's wives in America to serve soup to the farm workers at lunchtime, it forms part of the Great Bear constellation - not quite so easy to make out! The stars Merak and Dubhe form the pointers which will lead you to the Pole Star, and hence find North. The stars Alcor and Mizar form a naked eye double which repays observation in a small telescope as Mizar is then shown to be an easily resolved double star. A fainter reddish star forms a triangle with Alcor and Mizar.

Ursa Major contains many interesting "deep sky" objects. The brightest, listed in Messier's Catalogue, are shown on the chart, but there are many fainter galaxies in the region too. In the upper right of the constellation are a pair of interacting galaxies M81 and M82 shown in the image below. M82 is undergoing a major burst of star formation and hence called a "starburst galaxy". They can be seen together using a low power eyepiece on a small telescope.

Another, and very beautiful, galaxy is M101 which looks rather like a pinwheel firework, hence its other name the Pinwheel Galaxy. It was discovered in1781 and was a late entry to Messier's calalogue of nebulous objects. It is a type Sc spiral galaxy seen face on which is at a distance of about 24 million light years. Type Sc galaxies have a relativly small nucleus and open spiral arms. With an overall diameter of 170,000 light it is one of the largest spirals known (the Milky Way has a diameter of ~ 130,000 light years).

Though just outside the constellation boundary, M51 lies close to Alkaid, the leftmost star of the Plough. Also called the Whirlpool Galaxy it is being deformed by the passage of the smaller galaxy on the left. This is now gravitationally captured by M51 and the two will eventually merge. M51 lies at a distance of about 37 million light years and was the first galaxy in which spiral arms were seen. It was discovered by Charles Messier in 1773 and the spiral structure was observed by Lord Rosse in 1845 using the 72" reflector at Birr Castle in Ireland - for many years the largest telescope in the world.

Lying close to Merak is the planetary nebula M97 which is usually called the Owl Nebula due to its resemblance to an owl's face with two large eyes. It was first called this by Lord Rosse who drew it in 1848 - as shown in the image below right. Planetary nebulae ar the remnants of stars similar in size to our Sun. When all possible nuclear fusion processes are complete, the central core collpses down into a "white dwarf" star and the the outer parts of the star are blown off to form the surrounding nebula.