The Stars

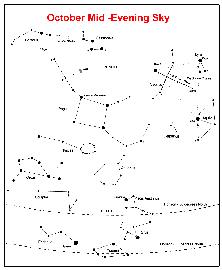

The Evening October Sky

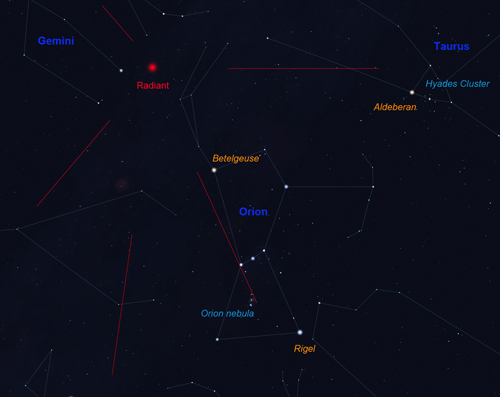

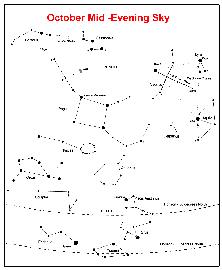

The October Sky in the south - mid evening

The October Sky in the south - mid evening

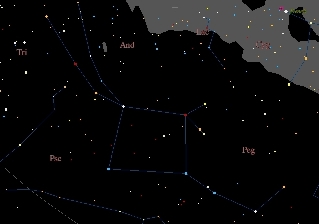

This map shows the constellations seen towards the south in mid evening. To the south in early evening - moving over to the west as the night progresses is the beautiful region of the Milky Way containing both Cygnus and Lyra. Below is Aquilla. The three bright stars Deneb (in Cygnus), Vega (in Lyra) and Altair (in Aquila) make up the "Summer Triangle". East of Cygnus is the great square of Pegasus - adjacent to Andromeda in which lies M31, the Andromeda Nebula. To the north lies "w" shaped Cassiopeia with Perseus below.

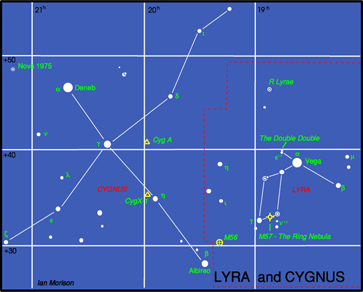

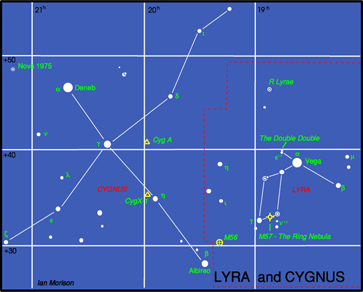

The constellations Lyra and Cygnus

Lyra and Cygnus

This month the constellations Lyra and Cygnus are seen almost overhead as darkness falls with their bright stars Vega, in Lyra, and Deneb, in Cygnus, making up the "summer triangle" of bright stars with Altair in the constellation Aquila below. (see sky chart above)

Lyra

Lyra is dominated by its brightest star Vega, the fifth brightest star in the sky. It is a blue-white star having a magnitude of 0.03, and lies 26 light years away. It weighs three times more than the Sun and is about 50 times brighter. It is thus burning up its nuclear fuel at a greater rate than the Sun and so will shine for a correspondingly shorter time. Vega is much younger than the Sun, perhaps only a few hundred million years old, and is surrounded by a cold,dark disc of dust in which an embryonic solar system is being formed!

There is a lovely double star called Epsilon Lyrae up and to the left of Vega. A pair of binoculars will show them up easily - you might even see them both with your unaided eye. In fact a telescope, provided the atmosphere is calm, shows that each of the two stars that you can see is a double star as well so it is called the double double!

Epsilon Lyra - The Double Double

Between Beta and Gamma Lyra lies a beautiful object called the Ring Nebula. It is the 57th object in the Messier Catalogue and so is also called M57. Such objects are called planetary nebulae as in a telescope they show a disc, rather like a planet. But in fact they are the remnants of stars, similar to our Sun, that have come to the end of their life and have blown off a shell of dust and gas around them. The Ring Nebula looks like a greenish smoke ring in a small telescope, but is not as impressive as it is shown in photographs in which you can also see the faint central "white dwarf" star which is the core of the original star which has collapsed down to about the size of the Earth. Still very hot this shines with a blue-white colour, but is cooling down and will eventually become dark and invisible - a "black dwarf"! Do click on the image below to see the large version - its wonderful!

M57 - the Ring Nebula

Image: Hubble Space telescope

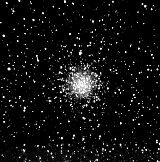

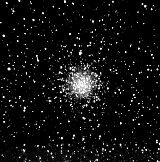

M56 is an 8th magnitude Globular Cluster visible in binoculars roughly half way between Alberio (the head of the Swan) and Gamma Lyrae. It is 33,000 light years away and has a diameter of about 60 light years. It was first seen by Charles Messier in 1779 and became the 56th entry into his catalogue.

M56 - Globular Cluster

Cygnus

Cygnus, the Swan, is sometimes called the "Northern Cross" as it has a distinctive cross shape, but we normally think of it as a flying Swan. Deneb,the arabic word for "tail", is a 1.3 magnitude star which marks the tail of the swan. It is nearly 2000 light years away and appears so bright only because it gives out around 80,000 times as much light as our Sun. In fact if Deneb where as close as the brightest star in the northern sky, Sirius, it would appear as brilliant as the half moon and the sky would never be really dark when it was above the horizon!

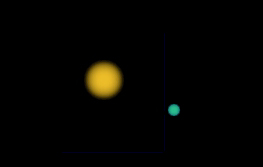

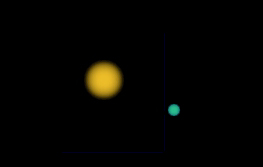

The star, Albireo, which marks the head of the Swan is much fainter, but a beautiful sight in a small telescope. This shows that Albireo is made of two stars, amber and blue-green, which provide a wonderful colour contrast. With magnitudes 3.1 and 5.1 they are regarded as the most beautiful double star that can be seen in the sky.

Alberio: Diagram showing the colours and relative brightnesses

Cygnus lies along the line of the Milky Way, the disk of our own Galaxy, and provides a wealth of stars and clusters to observe. Just to the left of the line joining Deneb and Sadr, the star at the centre of the outstretched wings, you may, under very clear dark skys, see a region which is darker than the surroundings. This is called the Cygnus Rift and is caused by the obscuration of light from distant stars by a lane of dust in our local spiral arm. the dust comes from elements such as carbon which have been built up in stars and ejected into space in explosions that give rise to objects such as the planetary nebula M57 described above.

There is a beautiful region of nebulosity up and to the left of Deneb which is visible with binoculars in a very dark and clear sky. Photographs show an outline that looks like North America - hence its name the North America Nebula. Just to its right is a less bright region that looks like a Pelican, with a long beak and dark eye, so not surprisingly this is called the Pelican Nebula. The photograph below shows them well.

The North American Nebula

Brocchi's Cluster An easy object to spot with binoculars in Gygnus is "Brocchi's Cluster", often called "The Coathanger",although it appears upside down in the sky! Follow down the neck of the swan to the star Alberio, then sweep down and to its lower left. You should easily spot it against the dark dust lane behind.

Brocchi's Cluster - The Coathanger

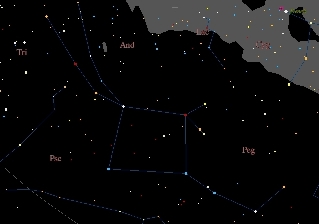

The constellations Pegasus and Andromeda

Pegasus and Andromeda

Pegasus and Andromeda

Pegasus

The Square of Pegasus is in the south during the evening and forms the body of the winged horse. The square is marked by 4 stars of 2nd and 3rd magnitude, with the top left hand one actually forming part of the constellation Andromeda. The sides of the square are almost 15 degrees across, about the width of a clentched fist, but it contains few stars visibe to the naked eye. If you can see 5 then you know that the sky is both dark and transparent! Three stars drop down to the right of the bottom right hand corner of the square marked by Alpha Pegasi, Markab. A brighter star Epsilon Pegasi is then a little up to the right, at 2nd magnitude the brightest star in this part of the sky. A little further up and to the right is the Globular Cluster M15. It is just too faint to be seen with the naked eye, but binoculars show it clearly as a fuzzy patch of light just to the right of a 6th magnitude star.

Andromeda

The stars of Andromeda arc up and to the left of the top left star of the square, Sirra or Alpha Andromedae. The most dramatic object in this constellation is M31, the Andromeda Nebula. It is a great spiral galaxy, similar to, but somewhat larger than, our galaxy and lies about 2.5 million light years from us. It can be seen with the naked eye as a faint elliptical glow as long as the sky is reasonably clear and dark. Move up and to the left two stars from Sirra, these are Pi amd Mu Andromedae. Then move your view through a rightangle to the right of Mu by about one field of view of a pair of binoculars and you should be able to see it easily. M31 contains about twice as many stars as our own galaxy, the Milky Way, and together they are the two largest members of our own Local Group of about 3 dozen galaxies.

M31 - The Andromeda Nebula

M31 - The Andromeda Nebula

M33 in Triangulum

If, using something like 8 by 40 binoculars, you have seen M31 as described above, it might well be worth searching for M33 in Triangulum. Triangulum is

the small faint constellation just below Andromeda. Start on M31, drop down to Mu Andromedae and keep on going in the same direction by the same distance as you have moved from M31 to Mu Andromedae. Under excellent seeing conditions (ie., very dark and clear skies) you should be able to see what looks like a little piece of tissue paper stuck on the sky or a faint cloud. It appears to have uniform brightness and shows no structure. The shape is irregular in outline - by no means oval in shape and covers an area about twice the size of the Moon. It is said that it is just visible to the unaided eye, so it the most distant object in the Universe that the eye can see. The distance is now thought to be 3.0 Million light years - just greater than that of M31.

M33 in triangulum - David Malin

M33 in triangulum - David Malin