An episode of beginnings! In the show this time, we talk to Emily Drabeck-Maunder about forming habitable planets, Mateusz Malenta rounds up the latest news, and we find out what we can see in the September night sky from Ian Morison and Gaby Perez.

The News

This month in the news: NASA goes all-American - again, the launch of the Parker solar probe, and getting in touch with Opportunity.

NASA is going back to all-American space with the August introduction of a new group of astronauts, who will be the first to fly from US soil, using US-built spacecraft since STS 135 in July 2011, which was the final flight of the Space Shuttle Atlantis and the final mission of the entire program. Since then, NASA had to rely on the help of its Russian counterpart, Roscosmos, to ferry its astronauts to the International Space Station and back onboard the Soyuz spacecraft. For many years, this has been seen as a less-than-ideal solution, with international and national pressures increasing even more in recent years to finally bring the capability to launch US astronauts from American soil. Initial plans involved launching an Orion spacecraft on top of the Ares I rocket, but they had to be revisited after the cancellation of the Constellation program in 2010. This meant that NASA was left with no replacement to the Space Shuttle, a situation it's been in for more than 7 years now.

Since then, more power and resources have been given to private contractors, small and big alike, with Boeing and SpaceX arguably the biggest winners to build and launch the first manned orbital spacecraft since the Space Shuttle, with their CST-100 Starliner and Crew Dragon 2 capsules respectively. Nine astronauts have been chosen to participate in 4 launches in total - 1 fight test and 1 mission flight for each of the capsules. These crews are made of both experienced astronauts and complete rookies.

The first Starliner mission will have a crew of three, including Eric Boe, who piloted Space Shuttles Endeavour and Discovery during the STS-126 and STS-133 missions respectively. He will be joined by another experienced pilot, Christopher Ferguson who flew and piloted a Space Shuttle on three separate occasions, during STS-115, STS-126, and STS-135. Ferguson officially left NASA in 2011 and joined Boeing, to become the first commercial astronaut. These two will be joined by Nicole Aunapu Mann, an Marine Corps test pilot, who is scheduled to go to space for the first time during that mission. Sunita Williams, a veteran NASA astronaut who was a commander of the ISS expedition 33 and is one of the most experienced spacewalkers from NASA, will fly onboard the Starliner during its second mission. She will share her duties with Josh Cassada on his first trip to space.

SpaceX's Crew Dragon 2 maiden crewed flight will have Robert Behnken and Douglas Hurley behind the wheel. Both are experienced NASA astronauts, with Behnken flying to space twice, during STS-123 and STS-130 and also performing multiple spacewalks. Hurley was a pilot during STS-127 and STS-135 missions. The second Dragon capsule launch will ferry Victor Glover, a Navy test pilot and astronaut rookie and Michael Hopkins, who spent 166 days in space during the Expedition 37/38 at the International Space Station.

The exact launch dates are still unknown, as both capsules are still under construction, with the first uncrewed flights expected at the end of this year or at the beginning of 2019, but some sources close to NASA say that these launches may slip as far back as late 2020. Additionally, NASA requires additional booster certification to prove they are safe for launching humans, which can move the ultimate launch of the first crewed mission an extra year or two into the future. This can be an extra challenge for SpaceX, with the company using a novel and slightly controversial 'load-and-go' method of fuelling their boosters minutes before the launch, meaning the crew would have to be already in the capsule, while the fuel tanks are being filled with a highly-explosive mixture. Due to the obvious safety concerns, NASA requires the company to successfully complete this procedure at least five times using the full uncrewed configuration before the first manned flight is allowed.

It's going to get warm for the Parker Solar Probe, launched aboard the Delta IV in the middle of the night on 12th August. If everything goes according to the plan, it will become the first spacecraft to fly through the solar corona, travelling at a distance as small as 6.2 million kilometres, less than a tenth of the largest distance between the Sun and Mercury, the planet closest to it in our Solar System. The close proximity to our star means that the spacecraft will have to withstand temperatures exceeding thousands of degrees Celsius and will be protected by more than 10 centimetres of shielding, made out of carbon composites.

Contrary to popular belief, sending payloads towards the Sun is more difficult than trying to get away, and this is reflected in the duration and complexity of the operations that will finally put the Probe on a stable orbit around the Sun. It will take around 7 years of Venus flybys, providing a necessary gravitational assist. During that time, the spacecraft will complete 24 orbits around the Sun, with speeds exceeding 700,000 kilometers per hour at its closest approach, which will make it the fastest spacecraft ever made. The instruments onboard the spacecraft cover a wide suite of measurements and will allow scientists to measure the strength and shape of the Sun's magnetic field, measure the velocity, density and temperature of electrons, protons and helium ions leaving the solar surface, and a camera to image ejecta originating at the Sun. The hope is that this mission will allow us to better understand the environment inside the Sun's atmosphere and explain why it is hundreds of times hotter that its surface. The examination of matter ejected from the Sun will help us to better understand the effect it has on space weather and the implications for the Earth's weather and climate patterns, as well as the effect the energetic solar particles have on the electronics in space as well as on the surface of our planet.

And finally an update on the status of the little rover that could, Opportunity, which has been silent since 10th June, when it went into hibernation mode due to a massive dust storm, a situation we have already talked about during our June Jodcast episode. At the end of July and beginning of August, the amount of dust in the Martian atmosphere decreased sufficiently for the JPL engineers to be hopeful that the rover would wake up and ping them. Unfortunately Opportunity has not phoned home yet.

This is not the first dust storm that the rover had to endure, but this is was one of the largest dust storms since it touched down on the surface of Mars more than 14 years ago, and it is not getting younger, with solar panels constantly covered by dust and deteriorating batteries. It is possible that this dust storm was one too many for Opportunity and it entered one of the fault modes with either the electric power system, internal clock or the communication systems giving up. The scientists are not losing hope just yet, as the rover is equipped with redundant systems which could help it to wake up and send signals back to Earth. Currently the efforts are concentrated on listening to the rover and all the signals coming from Mars across a large bandwidth. Engineers are also trying to talk to the rover multiple times per week in the hope of pinging it at a right time and starting the waking-up procedure. If all these efforts are in vain, NASA will continue to talk and listen to the rover on a regular basis for few months, until at least January 2019 when they will become more sporadic and eventually cease if Opportunity is considered to be in a permanent state of sleep.

Interview with Emily Drabeck-Maunder

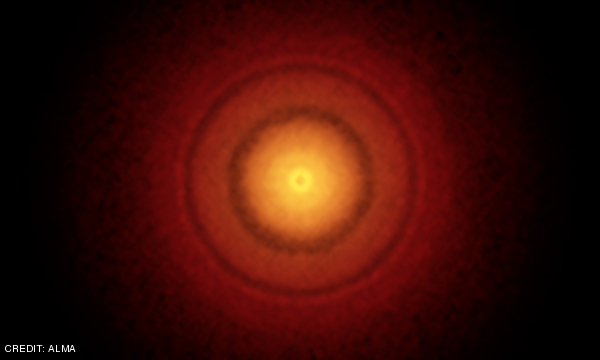

Emily Drabeck-Maunder from the University of Cardiff discusses how habitable planets might form within stellar disks, and how their signatures can be detected at radio wavelengths. In particular, the PEBBLES survey (of which Jodrell Bank is a part of) is looking to spot pebbles as they accrete into protoplanets, in order to gain insight into how our own Solar System might have come into being.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the Northern Hemisphere night sky during September 2018.

The Planets

- Jupiter - Jupiter can be seen in the west soon after sunset at the start of the month. It shines at magnitude -1.9 (falling to -1.8 during the month) and has a disk some 35 (falling to 33) arc seconds across. Jupiter's equatorial bands, sometimes the Great Red Spot and up to four of its Gallilean moons will be visible in a small telescope. Sadly, moving slowly eastwards in Libra during the month, Jupiter is heading towards the southern part of the ecliptic and will only have an elevation of ~10 degrees after sunset. Atmospheric dispersion will thus hinder our view and it might be worth considering purchasing the ZWO Atmospheric Dispersion Corrector to counteract its effects.

- Saturn - Saturn will be visible in the south at an elevation of ~14 degrees after sunset at the beginning of September. Its disk has an angular size of 17.5 arc seconds falling to 16.5 during the month. Its brightness reduces from +0.4 to +0.5 magnitudes as the month progresses. The rings were at their widest some months ago and are still, at 25 degrees to the line of sight, well open and spanning ~2.5 times the size of Saturn's globe. Saturn, lying in Sagittarius, halts its retrograde motion on the 6th within a few degrees of M8, the Lagoon Nebula, and M20, the Trifid Nebula. Sadly, atmospheric dispersion will greatly hinder our view and, as for Jupiter, it might be worth considering purchasing the ZWO Atmospheric Dispersion Corrector to counteract its effects.

- Mercury - Mercury can be seen low in the east-northeast some 30 to 45 minutes before sunrise during the first week of September. On the 5th and 6th, Mercury, shining at magnitude -1, is just over one degree from Regulus in Leo (at magnitude +1). Around the 11th of the month Mercury disappears into the Sun's glare as it moves towards superior conjunction (behind the Sun) on the 20th of the month.

- Mars - Mars, which ceased it retrograde motion westwards in Capricornus (and just moving into Sagittarius) at the beginning of the month made its closest approach to Earth since 2003 on the night of July 30th/31st. After sunset, Mars can be seen just east of south shining at a magnitude of -2.1 but this falls to -1.3 by month's end. Its angular size is 21 arc seconds at the start of the month falling to 16 arc seconds by the start of October. With a small telescope it should (but see below) be possible to spot details, such as Syrtis Major, on its salmon-pink surface. From the UK, it will only reach an elevation of ~14 degrees when due south and so, sadly, the atmosphere will hinder our view. Another reason for purchasing a ZWO Atmospheric Dispersion corrector? As I write this in August, the dust storm which has obscured much of the surface since the end of June appears to be subsiding so let's hope it clears during September.

- Venus - Venus, was at greatest elongation east on the 17th August but is now only seen low in the west southwest after sunset setting at about 80 (reducing to 45) minutes after the Sun. The planet brightens from -4.6 to a dazzling -4.8 magnitudes making it easier to spot in the Sun's glare. Binoculars might be needed to spot it but please do not use them until after the Sun has set. Its angular size increases from 29 to 46 arc seconds during the month as the percentage illuminated disk (its phase) narrows from 40% to just 17%.

- Early September - observe Mars. Mars came to its closest opposition to Earth since 2003 on the 27th July but, sadly two things have conspired to limit our views. From the UK its maximum elevation when on the meridian was only 12 degrees when observed from a latitude of +52 degrees. Thus the atmosphere has hindered our view and the use of an Atmospheric Dispersion Corrector may well help to alleviate its effects. The second problem was that, as sometimes happens, Mars has suffered a major dust storm which, at the end of July, was making it very difficult to observe any features on the surface. These can happen every six to eight years and can last for several months. A small scale dust storm began on May 30th and, by the 20th of June, had engulfed the whole planet. Happily, the dust storm has now subsided and so details on the surface such as Syrtis Major and the Hellas Basin will be visible in small telescopes.

- Early September - observe Saturn. Saturn which reached opposition on the 27th of June, is now low (at an elevation of ~14 degrees) in the south as darkness falls lying above the 'teapot' of Sagittarius. Held steady, binoculars should enable you to see Saturn's brightest moon, Titan, at magnitude 8.2. A small telescope will show the rings with magnifications of x25 or more and one of 6-8 inches aperture with a magnification of ~x200 coupled with a night of good "seeing" (when the atmosphere is calm) will show Saturn and its beautiful ring system in its full glory. As Saturn rotates quickly with a day of just 10 and a half hours, its equator bulges slightly and so it appears a little "squashed". Like Jupiter, it does show belts but their colours are muted in comparison. The thing that makes Saturn stand out is, of course, its ring system. The two outermost rings, A and B, are separated by a gap called Cassini's Division which should be visible in a telescope of 4 or more inches aperture if seeing conditions are good. Lying within the B ring, but far less bright and difficult to spot, is the C or Crepe Ring. Due to the orientation of Saturn's rotation axis of 27 degrees with respect to the plane of the solar system, the orientation of the rings as seen by us changes as it orbits the Sun and twice each orbit they lie edge on to us and so can hardly be seen. This last happened in 2009 and they are currently at an angle of 26 degrees to the line of sight. The rings will continue to narrow until March 2025 when they will appear edge-on again.

- September - evenings: - Find the globular cluster in Hercules and spot the "Double-double" in Lyra. Just to the left of the bright star Vega in Lyra is the multiple star system Epsilon Lyrae often called the double-double. With binoculars a binary star is seen but, when observed with a telescope, each of these two stars is revealed to be a double star - hence the name!

- September - evenings: - A good month to observe Neptune with a small telescope. Neptune comes into opposition - when it is nearest the Earth - on the 7th of September, so will be well placed both this month and next. Its magnitude is +7.9 so Neptune, with a disk just 3.7 arc seconds across, is easily spotted in binoculars lying in the constellation Aquarius over to the left of Lambda Aquarii as shown on the charts. It rises to an elevation of ~27 degrees when due south. Given a telescope of 8 inches or greater aperture and a dark transparent night it should even be possible to spot its moon Triton. (This is my objective around this month!)

- September - evening: find the 'Coathanger'. Looking upwards after dark you should spot the three stars making up the 'Summer Triangle'. The lowest is Altair in Aquilla, up to its right is Vega in Lyra and over to its left is Deneb in Cygnus. With binoculars sweep upwards about one third of the way from Altair towards Vega. You should spot a nice asterism, formally 'Brocchi's Cluster' but usually called the Coathanger. It is formed of a straight line of six stars below which is a 'hook' of four stars. A pretty object!

- September first week - after sunset: three planets towards the south and west. If clear after sunset one should be able to see Jupiter setting in the West, Saturn lying due South, and Mars in the South southeast.

- September 8th - before dawn: Mercury below a thin crescent Moon. If clear before dawn on the 8th, look for Mercury low in the east just below a thin crescent Moon. Binoculars might be needed but please do not use them after the Sun has risen.

- September 17th - early evening: Saturn below a first quarter Moon. This evening, if clear, Saturn will be seen just below a first quarter Moon - a nice photo opportunity!

- September 18th - evening: Mars to the lower left of a waxing gibbous Moon. This evening, if clear, Mars will be seen down to the left of a waxing gibbous Moon.

- September 29th - late evening : the Moon amongst the Hyades Cluster. As Taurus rises, one should be able to spot (if clear!) a waning gibbous Moon amongst the Hyades Cluster.

- September 18th: Mons Piton and Cassini. Best seen after First Quarter, Mons Piton is an isolated lunar mountain located in the eastern part of Mare Imbrium, south-east of the crater Plato and west of the crater Cassini. It has a diameter of 25 km and a height of 2.3 km. Its height was determined by the length of the shadow it casts. Cassini is a 57km crater that has been flooded with lava. The crater floor has then been impacted many times and holds within its borders two significant craters, Cassini A, the larger and Cassini B. North of Mons Piton can be seen a rift through the Alpine Mountains (Montes Alpes). Around 166 km long it has a thin rille along its center. I have never seen it, but have been able to image it as seen in the lunar section (The 8 day old Moon).

Highlights

Southern Hemisphere

In her final Night Sky segment, Gaby Perez from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the Southern Hemisphere night sky during September 2018.

- Introduction - Kia Ora everyone, Gabriela here from Wellington New Zealand looking up at our September Southern hemisphere night sky. We are finally seeing the end of the cold nights as we move into Spring. September is the time for Spring and we can see it in our gardens as well as our skies. Throughout the month you will notice that your days are slowly becoming longer and your nights will be getting shorter as the 22nd of September is the Spring Equinox, meaning that we will have nearly equal amounts of day and night and the days will continue to get longer as we move forward in time.

- The Planets - We will also notice some change in the elevation of the Sun as it has started appearing higher in our north sky and will continue to move higher throughout the month. In terms of the Moon, new moon will fall on the 9th so the beginning of the month will have the darkest skies which is perfect for viewing all the deep sky objects and the Moon will be full on the 25th of September. We still have quite a few planets in the sky found across the ecliptic. We have four naked-eye planets in our sky. The brightest of these will be Venus, our evening star. It will be on the western horizon shortly after sunset. Above Venus you will find Jupiter and up ahead, east of the zenith we have Mars. All three will be visible just after sunset as these planets appear very brightly in our sky. Mars has been especially bright this year, coming the closest it has to Earth in 15 years at the end of July and is still looking quite bright, about the same brightness as Jupiter but it is now moving away and will be appearing smaller in our skies. As the night gets darker we will see Saturn appearing in the North. The moon will be weaving its way through the planets throughout the month.

- Scorpius/Antares - Between Jupiter and Saturn you can find our 'winter' constellation Scorpius and its bright orange star, Antares (the rival of Mars). This giant red star marks the heart of the scorpion. But we don't have Scorpions in New Zealand so early Maori see it as a fish hook. And Antares is the bloody bait on the hook. Now Maori constellations, unlike European ones, change as the night changes or as the year does as they will appear at different angles and different locations. For example in the morning, Scorpius will appear on the horizon, hook side up. Then this shape becomes the Western 'Pou' or pillar holding up the sky. It is hooked over as it bears the heavy sky on it's back all alone in the west but in the east there are three 'pou'.

- Bootes /Argo Navis - We have another brilliant star in our sky. Arcturus, the brightest star in the constellation of Bootes, the fourth-brightest in the night sky, and will appear in our northwest sky with Canopus, the second brightest star on the south skyline. Both of these stars will appear to twinkle. Canopus can look a little like a traffic light as it flashes different colours and Arcturus will flash red and green. This happens when the stars are so close to the horizon and the light scatters and disperses as the light has to travel through a thicker atmosphere before it reaches our eyes. Canopus is in the constellation of Carina which is circumpolar to us here in New Zealand meaning we can see it at any time of the year and night. It was once a part of a bigger constellation, the Argo Navis. that has been split into the three. The giant boat, once the largest constellation, is now formed of Carina (the keel of the ship), Vela (the sails) and Puppis (the poop deck). Carina is found near the Southern Cross (Crux). Through a pair of binoculars you can spot Eta Carinae. A star which once shone brightly in our skies during an event known as 'an imposter supernova'. A supernova can happens at the end of star's life as it collapses in on itself in a massive explosion bursting out bits of gas and dust. Eta Carinae went through a similar event but has not come to the end of its life, it is still quite hardy. Now astronomers are keeping their eye on this star as it may go full supernova are maybe go through another similar event. It is now encased in a nebula and astronomers believe it to be a double star system.

- Southern Cross.The Southern Cross is easily spotted in the South using the pointer stars, Alpha and Beta Centauri point down to the Crux constellation. Also in the South we have a stunning new of our Milky Way galaxy, the bulge appearing between Scorpius and Sagittarius, marks the heart of our Milky Way.

- On moonless evenings in a dark sky the Zodiacal Light is visible in the west. It makes up faint light surrounding Venus and Jupiter. It is just sunlight reflecting off meteoric dust in the plane of the solar system. The dust may have come from a big comet, long ago. That will certainly be a sight to see!

- That's it from me here in Wellington, New Zealand. I wish you all clear skies and a fantastic Spring!

Odds and Ends

Currently, the Lovell telescope is down for an extended period of maintenance, returning to full operations later this year. In the meantime we've been timing a small subset of our usual hoard of pulsars using the smaller Mark II telescope. Mostly we time each pulsar about once per fortnight, but with Mark II we've been able to get observations much more frequently because we're timing fewer sources. As a consequence the pulsar group recently discovered two pulsar glitches had occured a mere two weeks apart in the pulsar PSR J0631+1036. Glitches are rare events in which a pulsar spontaneously increases its rotation rate. Their rarity makes them difficult to study and most pulsars that have glitched have been seen to do so only once. It's been some years since PSR J0631+1036 last glitched, so it's something of a surprise that 2 events occurred so close together in time. Had we been timing with our usual observing regime with Lovell, we would not have seen this as two small glitches but one larger glitch. This begs the question, how many other double glitches have we missed because of our observing limitations?!

We discuss the recent appearance of a hole in the International Space Station, which is currently (at time of recording) of unknown origin. The 2mm-diameter hole caused a small pressure fluctuation in the station on the evening of the 29th August, and was initially dealt with by an astronaut placing their thumb over the breach. The hole has now had a more permanent fix, but investigations are currently underway as to how it got there in the first place. One thing that has been ruled out is a meteorite or space junk impact, and it looks like the hole had been drilled... but by who?

What would happen if you fired Mars at the Earth-Moon system? Josh describes a new Martian ejection hypothesis, in which Mars and Venus formed at a similar distance from the Sun (allowing Mars to have an atmosphere and liquid water), but then has Mars expelled from its position via gravitational interaction to where it is now. Simulations put this possibility at around 10% - a low chance, but perhaps we're just living in the 10%?

Show Credits

| News: | Mateusz Malenta |

| Interview: | Emily Drabeck-Maunder and (the real) Josh Hayes |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and Gaby Perez |

| Presenters: | Emma Alexander, Josh Hayes and Benjamin Shaw |

| Editors: | Alex Clarke, Jake Staberg Morgan and Tom Scragg |

| Segment Voice: | Mike Peel |

| Website: | Jake Staberg Morgan and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Jake Staberg Morgan |

| Cover art: | An ALMA image of the young star TW Hydrae, with associated protoplanetary disk. CREDIT: ALMA |