The Night Sky November 2019

Compiled by Ian Morison

A Transit of Mercury on the afternoon of the 11th November.

The Leonid Meteor Shower on the morning of the 17th/18th November

This page, updated monthly, will let you know some of the things that you can look out for in the night sky. It lists the phases of the Moon, where you will see the naked-eye planets and describes some of the prominent constellations in the night sky during the month.

New(ish)

The author's: Astronomy Digest

which, over time, will provide useful and, I hope, interesting articles for all amateur astronomers. A further aim is to update and add new material to link with the books recently published by Cambridge University Press and which are described on the home page of the digest. It now includes nearly 70 illustrated articles.Image of the Month

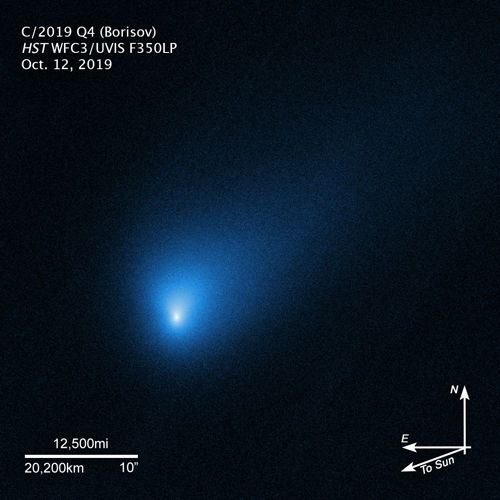

Comet Borizov

Comet 2I/Borisov has become the second recognised interstellar interloper. Like 'Oumuamua', Borisov's orbit and speed as it falls towards the Sun confirms that its origin is beyond our Solar System. At the time this Hubble image was taken, it lay about 418 million kilometres away and will make its closest approach to the Sun on December 7th at a distance of about 300 million kilometres or 2 Astronomical Units.

Highlights of the Month

November early mornings: November Meteors.

In the hours before dawn, November gives us a chance to observe meteors from two showers. The first that it is thought might produce some bright events is the Northern Taurids shower which has a broad peak of around 10 days but normally gives relatively few meteors per hour. The peak is around the 10th of November when the Moon is coming up to Full so its light may intrude. The meteors arise from comet 2P/Encke. Its tail is especially rich in large particles and, this year, we may pass through a relatively rich band so it is possible that a number of fireballs might be observed!

The better known November shower is the Leonids which peak on the night of the 17th/18th of the month. The Moon is coming up to Third Quarter so its light may again hinder our view - but the Leonids do contain some larger particles so some brighter meteors may well be seen. As one might expect, the shower's radiant lies within the sickle of Leo and meteors could be spotted from the 15th to the 20th of the month. The Leonids enter the atmosphere at ~71 km/sec and this makes them somewhat challenging to photograph but its worth trying as one might just capture a bright fireball. Up to 15 meteors an hour could be observed if near the zenith. The Leonids are famous becaus every 33 years a meteor storm might be observed when the parent comet, 55P/Temple-Tuttle passes close to the Sun. In 1999, 3,000 meteors were observed per hour but we are now halfway between these impressive events hence with a far lower expected rate.November - still a chance to observe Saturn.

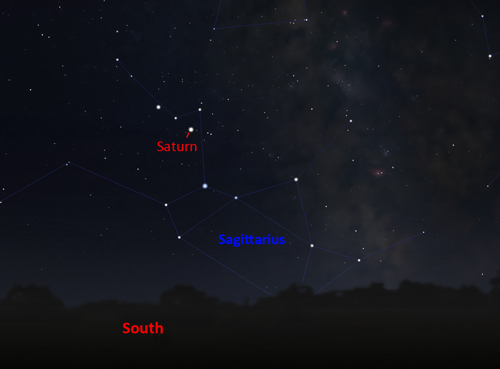

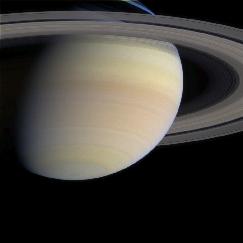

Saturn is now low (at an elevation of ~13 degrees) just west of south as darkness falls lying above the 'teapot' of Sagittarius. Held steady, binoculars should enable you to see Saturn's brightest moon, Titan, at magnitude 8.2. A small telescope will show the rings with magnifications of x25 or more and one of 6-8 inches aperture with a magnification of ~x200 coupled with a night of good "seeing" (when the atmosphere is calm) will show Saturn and its beautiful ring system in its full glory.

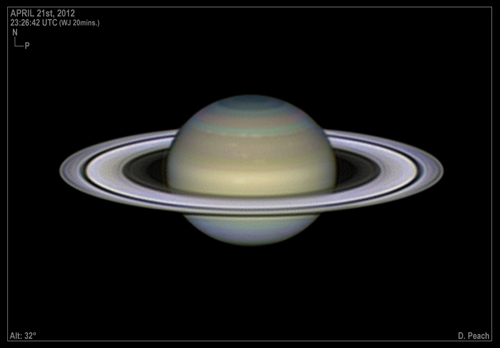

As Saturn rotates quickly with a day of just 10 and a half hours, its equator bulges slightly and so it appears a little "squashed". Like Jupiter, it does show belts but their colours are muted in comparison.

The thing that makes Saturn stand out is, of course, its ring system. The two outermost rings, A and B, are separated by a gap called Cassini's Division which should be visible in a telescope of 4 or more inches aperture if seeing conditions are good. Lying within the B ring, but far less bright and difficult to spot, is the C or Crepe Ring.

Due to the orientation of Saturn's rotation axis of 27 degrees with respect to the plane of the solar system, the orientation of the rings as seen by us changes as it orbits the Sun and twice each orbit they lie edge on to us and so can hardly be seen. This last happened in 2009 and they are currently at an angle of 25 degrees to the line of sight. The rings will continue to narrow until March 2025 when they will appear edge-on again.

See more of Damian Peach's images: Damian Peaches Website"

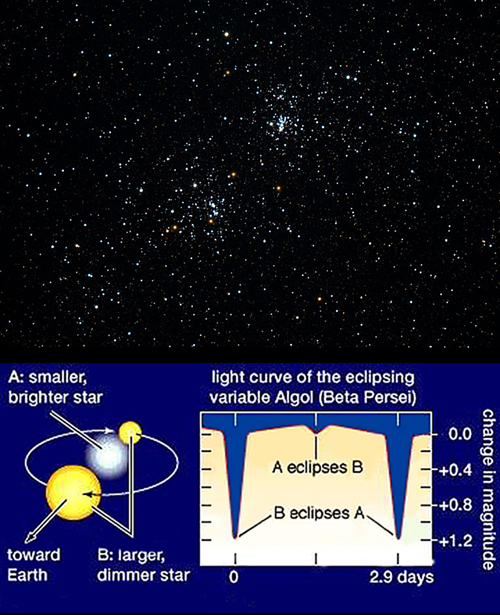

November, late evening: the Double Cluster and the 'Demon Star', Algol.

November is a good time to look high in the Southeast towards the constellations of Cassiopea and Perseus. Perseus contains two interesting objects; the Double Cluster between the two constellations and Algol the 'Demon Star'. Algol in an eclipsing binary system as seen in the diagram below. Normally the pair has a steady magnitude of 2.2 but every 2.86 days this briefly drops to magnitude 3.4.

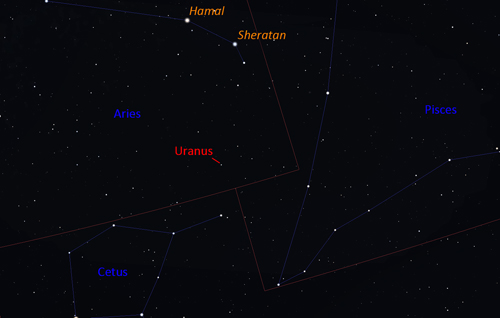

November: find Uranus.

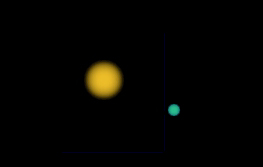

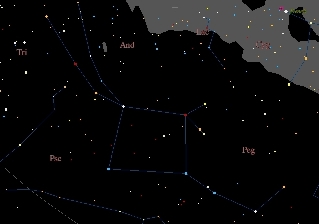

This month is a good time to find the planet Uranus in the late evening as it reached opposition on October 28th. With a magnitude of 5.7, binoculars will easily spot it and, from a really dark site, it might even be visible to the unaided eye. A medium aperture telescope will reveal Uranus's 3.7 arc second wide disk showing its turquoise colour. It lies in Aries, close to the boarders of Pisces and Cetus as shown on the chart.

November 1st - after sunset: A crescent Moon between Saturn and Jupiter

After sunset, low in the south-west, Jupiter will be seen down to the lower right of a waxing crescent Moon whilst, up and to its left, will be seen Saturn.

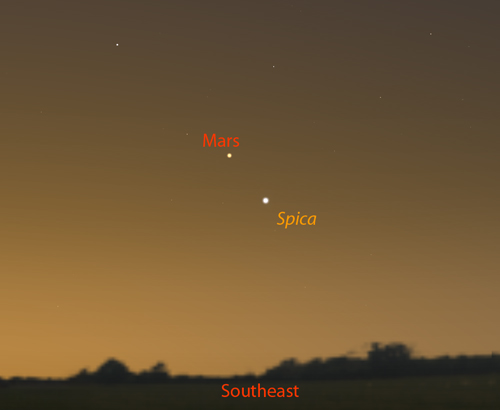

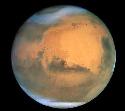

November 9th - before dawn: Mars lies above Spica.

Before dawn, low in the southeast, Mars (at magnitide 1.76) will be seen just above Spica (at magnitude 0.95) in Virgo.

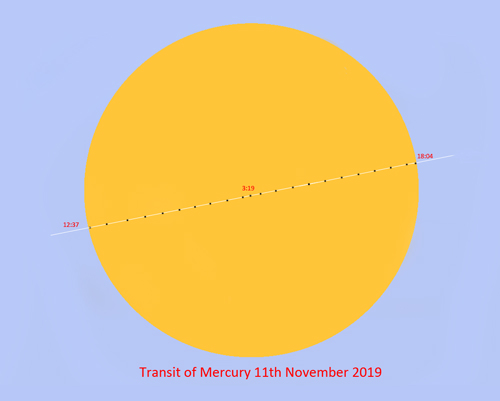

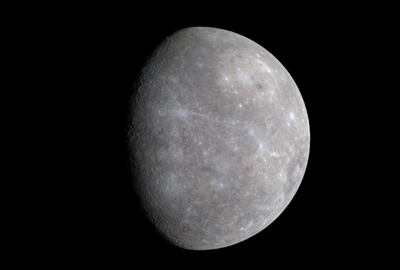

November 11th: A Transit of Mercury.

Whereas in 2016 the whole of the transit was visible, this year the Sun will have set (~4:16 pm) well before its end. First contact is at 12:35 when its disk will just impinge onto the Sun's surface with second contact at 12:37. Then, the Sun will have an elevation of ~20 degrees over the south-southwestern horizon. Mercury reaches the midway point of its transit at 3:19 - with the Sun at an elevation of just 7 degrees - but will be lost from view long before fourth contact as it leaves the Sun' surface at 6:04.

Mercury's disk is just 10 arc seconds across as compared to the Sun's 1938 arc seconds, so a small telescope would be needed to observe the transit should, hopefully, it be clear.

Any observation of the Sun can be dangerous unless proper precautions are taken and under no circumstances should one look directly at the Sun. One method is to project an image of the Sun's disk onto a white card mounted behind the telescope which has a shield surround to block the direct sunlight falling onto the card. Ensure that no one could look up towards the telescope eyepiece! A second approach is to buy a solar filter that is placed over the objective and taped in place so that there is no chance of it falling off. Baader Solar film can be purchased for about £20 so that one could make one's own - but great care is needed!

As the Sun is at solar minimum, it is unlikely that any sunspots will be visible to be confused with Mercury but, if so, Mercury's disk will appear darker and will, of course, be moving across the Sun's surface.

November 16th - late evening: the Moon in Gemini.

In the late evening, looking southeast, the waning Moon before third quarter will be seen within the constellation Gemini.

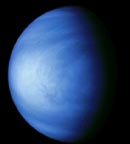

November 22nd - in twilight: Venus lies close to Jupiter.

After sunset, looking southwest, Venus will lie just two degrees below Jupiter - with Saturn high and away to the left.

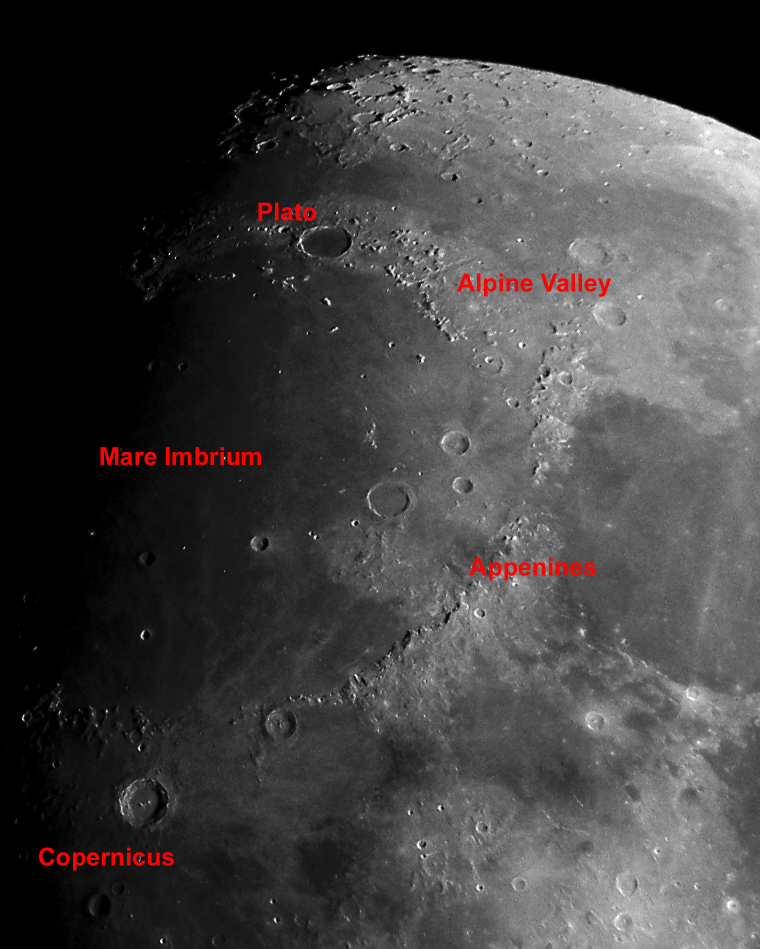

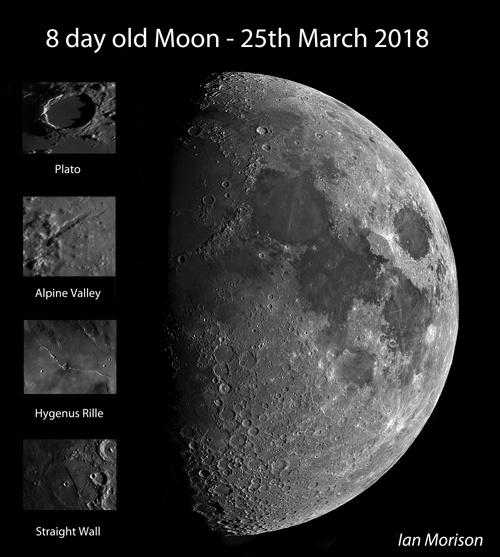

November 5th and 18th: The Alpine Valley

An interesting valley on the Moon: The Alpine Valley

These are two good nights to observe an interesting feature on the Moon if you have a small telescope. Close to the limb is the Appenine mountain chain that marks the edge of Mare Imbrium. Towards the upper end you should see the cleft across them called the Alpine valley. It is about 7 miles wide and 79 miles long. As shown in the image is a thin rill runs along its length which is quite a challenge to observe. The dark crater Plato will also be visible nearby. You may also see the shadow cast by the mountain Mons Piton lying not far away in Mare Imbrium. This is a very interesting region of the Moon!

M16, the Eagle nebula, imaged with the Faulkes Telescope

The Eagle Nebula, M16, imaged by Daniel Duggan.

This image was taken using the Faulkes Telescope North by Daniel Duggan - for some time a member of the Faulkes telescope team. It is a region of dust and gas where stars are now forming. The ultraviolet light from young blue stars is stripping the electrons from hydrogen atoms so this region contains ionized hydrogen and is called an HII region. As the electrons drop back down through the hydrogen energy levels as the atoms re-form, red light at the H alpha wavelength is emitted. This "true colour" image is composed of red, green and blue images along with a narrow band H alpha image. A Hubble image of the central region, called the "Pillars of Creation", has become quite famous but looks green/blue in colour. This is a false colour image where the H alpha image has been encoded as green!

Learn more about the Faulkes Telescopes and how schools can use them: Faulkes Telescope"

Observe the International Space Station

The International Space Station and Jules Verne passing behind the Lovell Telescope on April 1st 2008.

Image by Andrew Greenwood

Use the link below to find when the space station will be visible in the next few days. In general, the space station can be seen either in the hour or so before dawn or the hour or so after sunset - this is because it is dark and yet the Sun is not too far below the horizon so that it can light up the space station. As the orbit only just gets up the the latitude of the UK it will usually be seen to the south, and is only visible for a minute or so at each sighting. Note that as it is in low-earth orbit the sighting details vary quite considerably across the UK. The NASA website linked to below gives details for several cities in the UK. (Across the world too for foreign visitors to this web page.)

Note: I observed the ISS three times recently and was amazed as to how bright it has become.

Find details of sighting possibilities from your location from: Location Index

See where the space station is now: Current Position

The Moon

The Moon at 3rd Quarter. Image, by Ian Morison, taken with a 150mm Maksutov-Newtonian and Canon G7.

Just below the crator Plato seen near the top of the image is the mountain "Mons Piton". It casts a long shadow across the maria from which one can calculate its height - about 6800ft or 2250m.

| new moon | first quarter | full moon | third quarter |

|---|---|---|---|

| November 28th | November 5th | November 12th | November 20th |

Some Lunar Images by Ian Morison, Jodrell Bank Observatory: Lunar Images

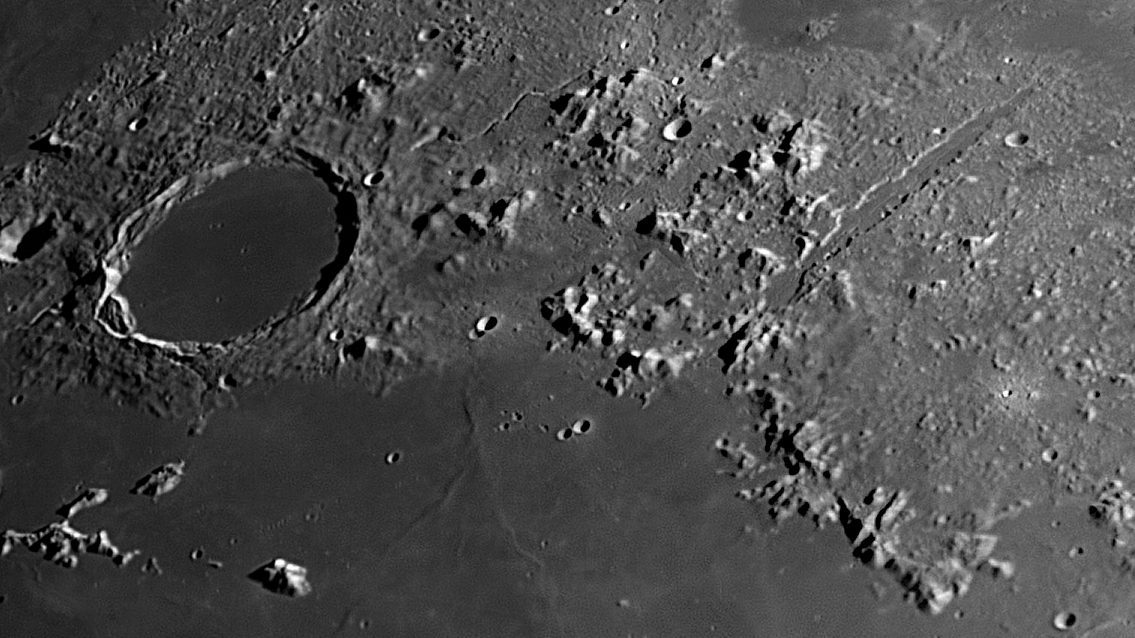

A World Record Lunar Image

To mark International Year of Astronomy, a team of British astronomers have made the largest lunar image in history and gained a place in the Guinness Book of Records! The whole image comprises 87.4 megapixels with a Moon diameter of 9,550 pixels. The resolution of ~0.4 arc seconds allows details as small as 1km across to be discerned! The superb quality of the image is shown by the detail below of Plato and the Alpine Valley. Craterlets are seen on the floor of Plato and the rille along the centre of the Alpine valley is clearly visible. The image quality is staggering! The team of Damian Peach, Pete lawrence, Dave Tyler, Bruce Kingsley, Nick Smith, Nick Howes, Trevor Little, David Mason, Mark and Lee Irvine with technical support from Ninian Boyle captured the video sequences from which 288 individual mozaic panes were produced. These were then stitched together to form the lunar image.

Please follow the link to the Lunar World Record website and it would be really great if you could donate to Sir Patrick Moore's chosen charity to either download a full resolution image or purchase a print.

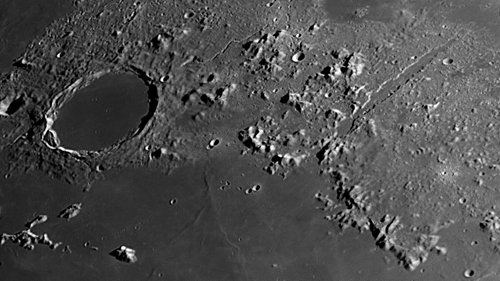

The 8 day old Moon

This image was taken by the author on a night in March 2018 when the Moon was at an elevation of ~52 degrees and the seeing was excellent. This enabled the resolution of the image to be largely determined by the resolution of the 200 mm aperture telescope and the 3.75 micron pixel size of the Point Grey Chameleon 1.3 megapixel video camera. The use of a near infrared filter allowed imaging to take place before it was dark and also reduced the effects of atmospheric turbulence. The 'Drizzle' technique developed by the Hubble Space Telescope Institute (HSTI) was used to reduce the effective size of the camera's pixels to allow the image to be well sampled. Around 100 gigabytes of data, acquired over a 2 hour period, was processed to produce images of 54 overlapping areas of the Moon which were then combined to give the full lunar disk in the free 'stitching' program Microsoft ICE. A further HSTI development called 'deconvolution sharpening' was then applied to the image. The Moon's disk is ~6,900 pixels in height and has a resolution of 0.6 to 0.7 arc seconds. Interestingly, as seen in the inset image, the rille lying along the centre of the Alpine Valley is just discernable and this is only ~0.5 km wide! [Due to size limitations the large image is 2/3 full size.]

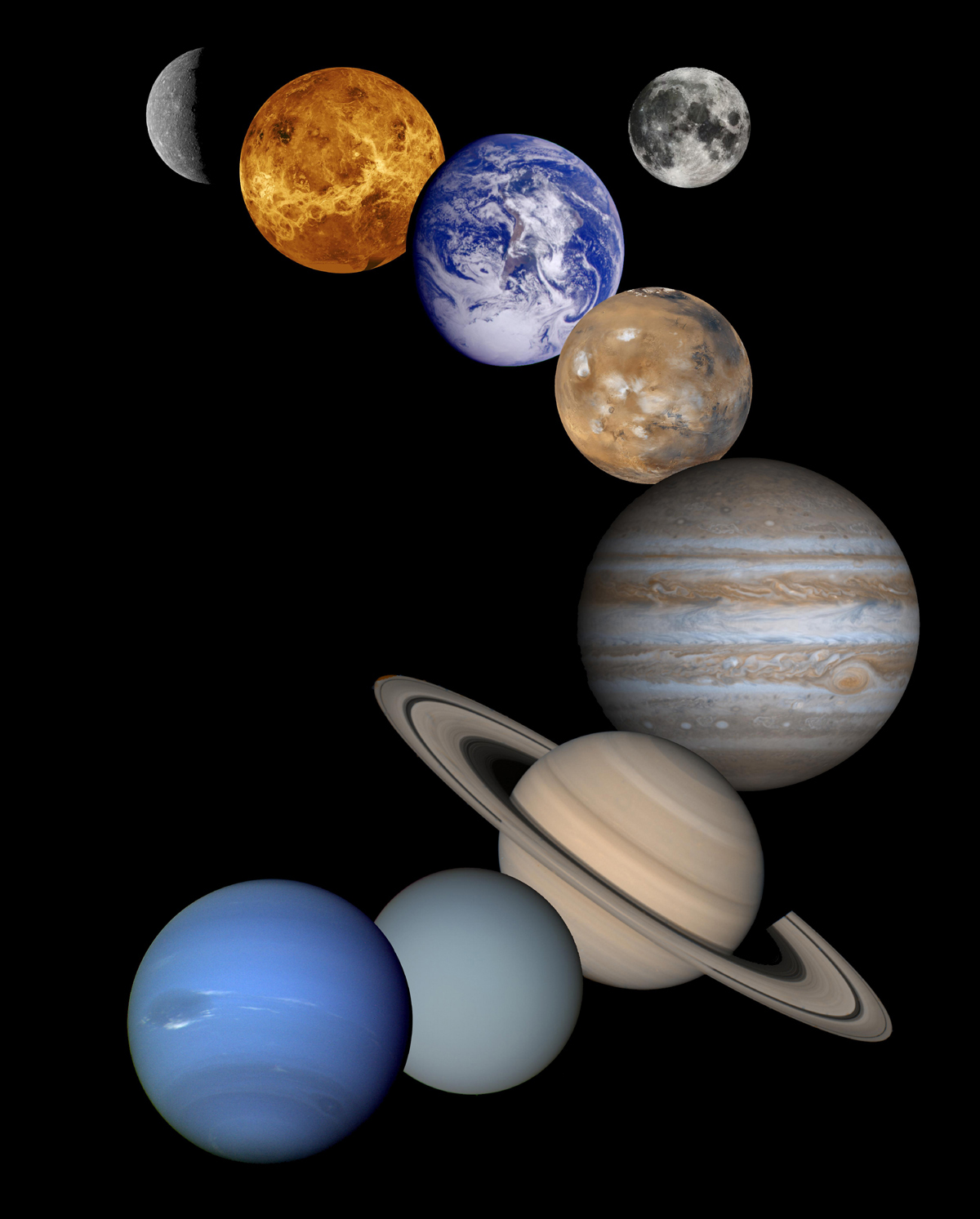

The Planets

Jupiter

Jupiter, shining on the 1st at magnitude -1.9 and falling to -1.8 during the month, can be seen very low in the southwest as darkness falls. As the month progresses, its angular size drops from 33.4 to 32.1 arc seconds but, by the end of the month, will be lost in the Sun's glare. Jupiter lies in the southeastern part of Ophiuchus and is heading towards the southernmost part of the ecliptic so, as it appears in the twilight, will only have an elevation of ~8 degrees. With its low elevation, atmospheric dispersion will take its toll and an atmospheric dispersion corrector would greatly help to improve our views of the giant planet and it four Gallilean moons.

Saturn

Saturn, will be seen just west of south as darkness falls at the start of the month. Then, its disk is ~16 arc seconds across and its rings - which are still, at 25.2 degrees, nicely tilted from the line of sight - spanning some 39 arc seconds across. During the month its brightness remains +0.6 whilst its angular size falls to 15.4 arc seconds. Sadly, now in Sagittarius and lying on the south-eastern side of the milky way, it is at the lowest point of the ecliptic and will only reach an elevation of ~13 degrees. As with Jupiter, an atmospheric dispersion corrector will help improve our view.

Mercury

Mercury. Following its transit of the Sun on the 11th - see Highlight above - Mercury rises rapidly into the pre-dawn sky, increasing in brightness by half a magnitude each day and rising about 7 minutes earlier as the days progress. The rates slow until Mercury reaches greatest western elongation some 20 degrees in angle from the Sun on the 28th. By then, it will have brightened to magnitude -0.5 and will rise one and a quarter hours before the Sun. It will then have an elevation of some 11 degrees before being lost in the Sun's glare.

Mars

Mars which passed behind the Sun (superior conjunction) on September 2nd, can be seen in the pre-dawn sky at the start of its new apparition. It might just be glimpsed just south of east at the start of the month but will then only have an elevation of ~11 degrees at sunrise. Then, binoculars could well be needed to spot its +1.8th magnitude, 3.7 arc second disk - but please do not use them after the Sun has risen. However, by the end of the month, Mars rises some two and a half hours before the Sun remaining at magnitude -2.8 with disk still less than 4 arc seconds across. It will have risen to ~12 degrees elevation before being lost in the Sun's glare.

Venus

Venus may just be glimpsed in the west south-west setting an hour after the Sun at the start of the month, but will be difficult to see due to the fact that the ecliptic is at a shallow angle to the horizon and so Venus will have a very low elevation. By month's end, the Sun sets just before 4 pm and Venus an hour and a quarter later but it will still be hard to spot with an elevation of just 6 degrees as darknes falls. Its magnitude remains at about -3.8 and its, almost fully illuminated disk, is ~11 arc seconds across. Binoculars and a very low horizon will be needed to spot Venus, but please do not use them until after the Sun has set.

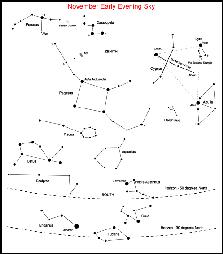

The Evening November Sky

This map shows the constellations seen towards the south in early evening. To the south in early evening moving over to the west as the night progresses is the beautiful region of the Milky Way containing both Cygnus and Lyra. Below is Aquilla. The three bright stars Deneb (in Cygnus), Vega (in Lyra) and Altair (in Aquila) make up the "Summer Triangle". East of Cygnus is the great square of Pegasus - adjacent to Andromeda in which lies M31, the Andromeda Nebula. To the north lies "w" shaped Cassiopeia and Perseus. The constellation Taurus, with its two lovely clusters, the Hyades and Pleiades is rising in the east during the late evening.

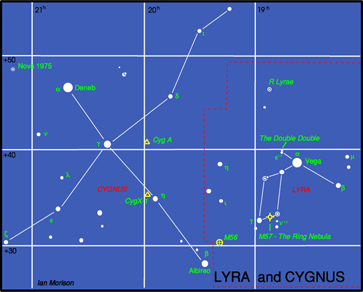

The constellations Lyra and Cygnus

This month the constellations Lyra and Cygnus are seen almost overhead as darkness falls with their bright stars Vega, in Lyra, and Deneb, in Cygnus, making up the "summer triangle" of bright stars with Altair in the constellation Aquila below. (see sky chart above)

Lyra

Lyra is dominated by its brightest star Vega, the fifth brightest star in the sky. It is a blue-white star having a magnitude of 0.03, and lies 26 light years away. It weighs three times more than the Sun and is about 50 times brighter. It is thus burning up its nuclear fuel at a greater rate than the Sun and so will shine for a correspondingly shorter time. Vega is much younger than the Sun, perhaps only a few hundred million years old, and is surrounded by a cold,dark disc of dust in which an embryonic solar system is being formed!

There is a lovely double star called Epsilon Lyrae up and to the left of Vega. A pair of binoculars will show them up easily - you might even see them both with your unaided eye. In fact a telescope, provided the atmosphere is calm, shows that each of the two stars that you can see is a double star as well so it is called the double double!

Between Beta and Gamma Lyra lies a beautiful object called the Ring Nebula. It is the 57th object in the Messier Catalogue and so is also called M57. Such objects are called planetary nebulae as in a telescope they show a disc, rather like a planet. But in fact they are the remnants of stars, similar to our Sun, that have come to the end of their life and have blown off a shell of dust and gas around them. The Ring Nebula looks like a greenish smoke ring in a small telescope, but is not as impressive as it is shown in photographs in which you can also see the faint central "white dwarf" star which is the core of the original star which has collapsed down to about the size of the Earth. Still very hot this shines with a blue-white colour, but is cooling down and will eventually become dark and invisible - a "black dwarf"! Do click on the image below to see the large version - its wonderful!

M56 is an 8th magnitude Globular Cluster visible in binoculars roughly half way between Albireo (the head of the Swan) and Gamma Lyrae. It is 33,000 light years away and has a diameter of about 60 light years. It was first seen by Charles Messier in 1779 and became the 56th entry into his catalogue.

Cygnus

Cygnus, the Swan, is sometimes called the "Northern Cross" as it has a distinctive cross shape, but we normally think of it as a flying Swan. Deneb,the arabic word for "tail", is a 1.3 magnitude star which marks the tail of the swan. It is nearly 2000 light years away and appears so bright only because it gives out around 80,000 times as much light as our Sun. In fact if Deneb where as close as the brightest star in the northern sky, Sirius, it would appear as brilliant as the half moon and the sky would never be really dark when it was above the horizon!

The star, Albireo, which marks the head of the Swan is much fainter, but a beautiful sight in a small telescope. This shows that Albireo is made of two stars, amber and blue-green, which provide a wonderful colour contrast. With magnitudes 3.1 and 5.1 they are regarded as the most beautiful double star that can be seen in the sky.

Cygnus lies along the line of the Milky Way, the disk of our own Galaxy, and provides a wealth of stars and clusters to observe. Just to the left of the line joining Deneb and Sadr, the star at the centre of the outstretched wings, you may, under very clear dark skys, see a region which is darker than the surroundings. This is called the Cygnus Rift and is caused by the obscuration of light from distant stars by a lane of dust in our local spiral arm. the dust comes from elements such as carbon which have been built up in stars and ejected into space in explosions that give rise to objects such as the planetary nebula M57 described above.

There is a beautiful region of nebulosity up and to the left of Deneb which is visible with binoculars in a very dark and clear sky. Photographs show an outline that looks like North America - hence its name the North America Nebula. Just to its right is a less bright region that looks like a Pelican, with a long beak and dark eye, so not surprisingly this is called the Pelican Nebula. The photograph below shows them well.

Brocchi's Cluster An easy object to spot with binoculars in Gygnus is "Brocchi's Cluster", often called "The Coathanger",although it appears upside down in the sky! Follow down the neck of the swan to the star Albireo, then sweep down and to its lower left. You should easily spot it against the dark dust lane behind.

The constellations Pegasus and Andromeda

Pegasus

The Square of Pegasus is in the south during the evening and forms the body of the winged horse. The square is marked by 4 stars of 2nd and 3rd magnitude, with the top left hand one actually forming part of the constellation Andromeda. The sides of the square are almost 15 degrees across, about the width of a clentched fist, but it contains few stars visibe to the naked eye. If you can see 5 then you know that the sky is both dark and transparent! Three stars drop down to the right of the bottom right hand corner of the square marked by Alpha Pegasi, Markab. A brighter star Epsilon Pegasi is then a little up to the right, at 2nd magnitude the brightest star in this part of the sky. A little further up and to the right is the Globular Cluster M15. It is just too faint to be seen with the naked eye, but binoculars show it clearly as a fuzzy patch of light just to the right of a 6th magnitude star.

Andromeda

The stars of Andromeda arc up and to the left of the top left star of the square, Sirra or Alpha Andromedae. The most dramatic object in this constellation is M31, the Andromeda Nebula. It is a great spiral galaxy, similar to, but somewhat larger than, our galaxy and lies about 2.5 million light years from us. It can be seen with the naked eye as a faint elliptical glow as long as the sky is reasonably clear and dark. Move up and to the left two stars from Sirra, these are Pi amd Mu Andromedae. Then move your view through a rightangle to the right of Mu by about one field of view of a pair of binoculars and you should be able to see it easily. M31 contains about twice as many stars as our own galaxy, the Milky Way, and together they are the two largest members of our own Local Group of about 3 dozen galaxies.

M33 in Triangulum

If, using something like 8 by 40 binoculars, you have seen M31 as described above, it might well be worth searching for M33 in Triangulum. Triangulum is

the small faint constellation just below Andromeda. Start on M31, drop down to Mu Andromedae and keep on going in the same direction by the same distance as you have moved from M31 to Mu Andromedae. Under excellent seeing conditions (ie., very dark and clear skies) you should be able to see what looks like a little piece of tissue paper stuck on the sky or a faint cloud. It appears to have uniform brightness and shows no structure. The shape is irregular in outline - by no means oval in shape and covers an area about twice the size of the Moon. It is said that it is just visible to the unaided eye, so it the most distant object in the Universe that the eye can see. The distance is now thought to be 3.0 Million light years - just greater than that of M31.

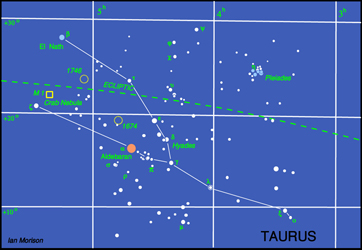

The constellation Taurus

Taurus is one of the most beautiful constellations and you can almost imagine the Bull charging down to the left towards Orion. His face is delineated by the "V" shaped cluster of stars called the Hyades, his eye is the red giant star Aldebaran and the tips of his horns are shown by the stars beta and zeta Tauri. Although alpha Tauri, Aldebaran, appears to lie amongst the stars of the Hyades cluster it is, in fact, less than half their distance lying 68 light years away from us. It is around 40 times the diameter of our Sun and 100 times as bright.

More beautiful images by Alson Wong : Astrophotography by Alson Wong

To the upper right of Taurus lies the open cluster, M45, the Pleiades. Often called the Seven Sisters, it is one of the brightest and closest open clusters. The Pleiades cluster lies at a distance of 400 light years and contains over 3000 stars. The cluster, which is about 13 light years across, is moving towards the star Betelgeuse in Orion. Surrounding the brightest stars are seen blue reflection nebulae caused by reflected light from many small carbon grains. These relfection nebulae look blue as the dust grains scatter blue light more efficiently than red. The grains form part of a molecular cloud through which the cluster is currently passing. (Or, to be more precise, did 400 years ago!)

Close to the tip of the left hand horn lies the Crab Nebula, also called M1 as it is the first entry of Charles Messier's catalogue of nebulous objects. Lying 6500 light years from the Sun, it is the remains of a giant star that was seen to explode as a supernova in the year 1056. It may just be glimpsed with binoculars on a very clear dark night and a telescope will show it as a misty blur of light.

Its name "The Crab Nebula" was given to it by the Third Earl of Rosse who observed it with the 72 inch reflector at Birr Castle in County Offaly in central Ireland. As shown in the drawing above, it appeared to him rather lile a spider crab. The 72 inch was the world's largest telelescope for many years. At the heart of the Crab Nebula is a neutron star, the result of the collapse of the original star's core. Although only around 20 km in diameter it weighs more than our Sun and is spinning 30 times a second. Its rotating magnetic field generate beams of light and radio waves which sweep across the sky. As a result, a radio telescope will pick up very regular pulses of radiation and the object is thus also known a Pulsar. Its pulses are monitored each day at Jodrell Bank with a 13m radio telescope.