The Stars

The Mid to Late Evening January Sky

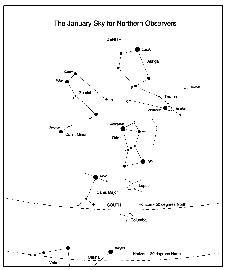

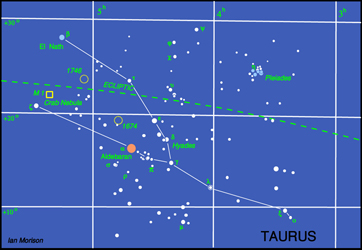

The January Sky in the south - mid to late evening.

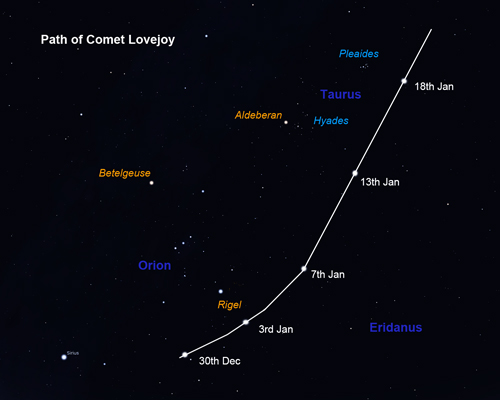

This map shows the constellations seen in the south around midnight. The brilliant constellation of Orion is seen in the south. Moving up and to the right - following the line of the three stars of Orion's belt - brings one to Taurus; the head of the bull being outlined by the V-shaped cluster called the Hyades with its eye delineated by the orange red star Aldebaran. Further up to the right lies the Pleaides Cluster. Towards the zenith from Taurus lies the constellation Auriga, whose brightest star Capella will be nearly overhead. To the upper left of Orion lie the heavenly twins, or Gemini , their heads indicated by the two bright stars Castor and Pollux. Down to the lower left of Orion lies the brightest star in the northern sky, Sirius, in the consteallation Canis Major. Finally, up and to the left of Sirius is Procyon in Canis Minor. There is also information about the constellation Ursa Major, seen in the north,in the constellation details below.

The constellation Taurus

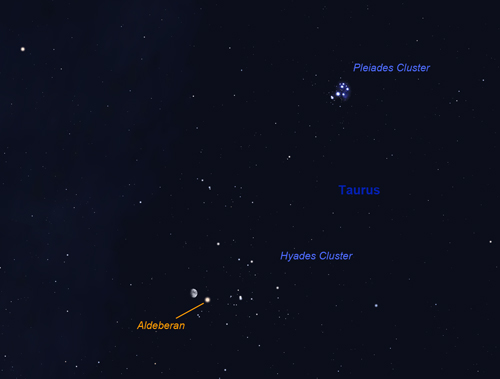

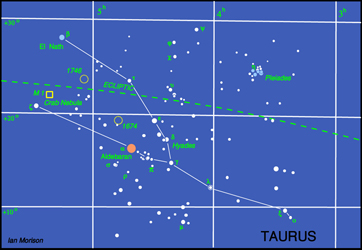

Taurus

Taurus is one of the most beautiful constellations and you can almost imagine the Bull charging down to the left towards Orion. His face is delineated by the "V" shaped cluster of stars called the Hyades, his eye is the red giant star Aldebaran and the tips of his horns are shown by the stars beta and zeta Tauri. Although alpha Tauri, Aldebaran, appears to lie amongst the stars of the Hyades cluster it is, in fact, less than half their distance lying 68 light years away from us. It is around 40 times the diameter of our Sun and 100 times as bright.

AAO Image of the Pleiades, M45, by David Malin

To the upper right of Taurus lies the open cluster, M45, the Pleiades. Often called the Seven Sisters, it is one of the brightest and closest open clusters. The Pleiades cluster lies at a distance of 400 light years and contains over 3000 stars. The cluster, which is about 13 light years across, is moving towards the star Betelgeuse in Orion. Surrounding the brightest stars are seen blue reflection nebulae caused by reflected light from many small carbon grains. These relfection nebulae look blue as the dust grains scatter blue light more efficiently than red. The grains form part of a molecular cloud through which the cluster is currently passing. (Or, to be more precise, did 400 years ago!)

VLT image of the Crab Nebula

Close to the tip of the left hand horn lies the Crab Nebula, also called M1 as it is the first entry of Charles Messier's catalogue of nebulous objects. Lying 6500 light years from the Sun, it is the remains of a giant star that was seen to explode as a supernova in the year 1056. It may just be glimpsed with binoculars on a very clear dark night and a telescope will show it as a misty blur of light.

Lord Rosse's drawing of M1

Its name "The Crab Nebula" was given to it by the Third Earl of Rosse who observed it with the 72 inch reflector at Birr Castle in County Offaly in central Ireland. As shown in the drawing above, it appeared to him rather lile a spider crab. The 72 inch was the world's largest telelescope for many years. At the heart of the Crab Nebula is a neutron star, the result of the collapse of the original star's core. Although only around 20 km in diameter it weighs more than our Sun and is spinning 30 times a second. Its rotating magnetic field generate beams of light and radio waves which sweep across the sky. As a result, a radio telescope will pick up very regular pulses of radiation and the object is thus also known a Pulsar. Its pulses are monitored each day at Jodrell Bank with a 13m radio telescope.

The constellation Orion

Orion

Orion, perhaps the most beautiful of constellations, will be seen in the south at around 11 - 12 pm during January. Orion is the hunter holding up a club and shield against the charge of Taurus, the Bull up and to his right. Alpha Orionis, or Betelgeuse, is a read supergiant star varying in size between three and four hundred times that of our Sun. The result is that its brightness varies somewhat. Beta Orionis, or Rigel, is a blue supergiant which, at around 1000 light years distance is about twice as far away as Betelgeuse. It has a 7th magnitude companion. The three stars of Orion's belt lie at a distance of around 1500 light years. Just below the lower left hand star lies a strip of nebulosity against which can be seen a pillar of dust in the shape of the chess-board knight. It is thus called the Horsehead Nebula. It shows up very well photographically but is exceedingly difficult to see visually - even with relativly large telescope.

The Horsehead Nebula: Anglo Australian Observatory

Beneath the central star of the belt lies Orion's sword containing one of the most beautiful sights in the heavens - The Orion Nebula. It is a region of star formation and the reddish colour seen in photographs comes from Hydrogen excited by ultraviolet emitted from the very hot young stars that make up the Trapesium which is at its heart. The nebula, cradling the trapesium stars, is a beautiful sight in binoculars or, better still, a telescope. To the eye it appears greenish, not red, as the eye is much more sensitive to the green light emitted by ionized oxygen than the reddish glow from the hydrogen atoms.

The Orion Nebula: David Malin

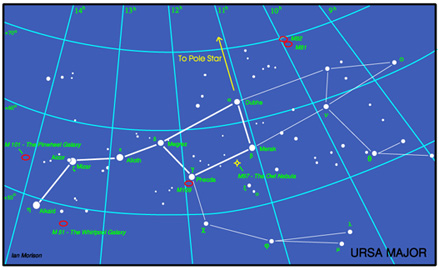

The constellation Ursa Major

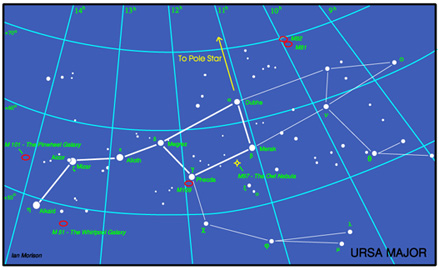

Ursa Major

The stars of the Plough, shown linked by the thicker lines in the chart above, form one of the most recognised star patterns in the sky. Also called the Big Dipper, after the soup ladles used by farmer's wives in America to serve soup to the farm workers at lunchtime, it forms part of the Great Bear constellation - not quite so easy to make out! The stars Merak and Dubhe form the pointers which will lead you to the Pole Star, and hence find North. The stars Alcor and Mizar form a naked eye double which repays observation in a small telescope as Mizar is then shown to be an easily resolved double star. A fainter reddish star forms a triangle with Alcor and Mizar.

Ursa Major contains many interesting "deep sky" objects. The brightest, listed in Messier's Catalogue, are shown on the chart, but there are many fainter galaxies in the region too. In the upper right of the constellation are a pair of interacting galaxies M81 and M82 shown in the image below. M82 is undergoing a major burst of star formation and hence called a "starburst galaxy". They can be seen together using a low power eyepiece on a small telescope.

M81 and M82

Another, and very beautiful, galaxy is M101 which looks rather like a pinwheel firework, hence its other name the Pinwheel Galaxy. It was discovered in1781 and was a late entry to Messier's calalogue of nebulous objects. It is a type Sc spiral galaxy seen face on which is at a distance of about 24 million light years. Type Sc galaxies have a relativly small nucleus and open spiral arms. With an overall diameter of 170,000 light it is one of the largest spirals known (the Milky Way has a diameter of ~ 130,000 light years).

M101 - The Ursa Major Pinwheel Galaxy

Though just outside the constellation boundary, M51 lies close to Alkaid, the leftmost star of the Plough. Also called the Whirlpool Galaxy it is being deformed by the passage of the smaller galaxy on the left. This is now gravitationally captured by M51 and the two will eventually merge. M51 lies at a distance of about 37 million light years and was the first galaxy in which spiral arms were seen. It was discovered by Charles Messier in 1773 and the spiral structure was observed by Lord Rosse in 1845 using the 72" reflector at Birr Castle in Ireland - for many years the largest telescope in the world.

M51 - The Whirlpool Galaxy

Lying close to Merak is the planetary nebula M97 which is usually called the Owl Nebula due to its resemblance to an owl's face with two large eyes. It was first called this by Lord Rosse who drew it in 1848 - as shown in the image below right. Planetary nebulae ar the remnants of stars similar in size to our Sun. When all possible nuclear fusion processes are complete, the central core collpses down into a "white dwarf" star and the the outer parts of the star are blown off to form the surrounding nebula.

M97 - The Owl Planetary Nebula Lord Rosse's 1848 drawing of the Owl Nebula