In the show this time, we talk to Stewart Eyres about his study of a star that blew up a long time ago, Luke Hart rounds up the news that has happened in the near past, and we find out what we can see in the Month 4 night sky from Ian Morison, Haritina Mogosanu and Samuel Leske.

The News

This month in the news: shut-downs and space sightings.

First, some news about what has been happening at our space building. Since we started making this month’s show, the place of higher learning in Manchester decided to shut down all its buildings to help keep students and people who work there safe, so we can no longer get into our space building. Because of this, the Jodcast will sound a little different - because we can’t use the room where we make our voices into computer sounds - and might not have all the usual things we talk about in it. Even though we might not sound as good as usual, though, we’ll do our best to keep the show going out.

Our space building isn’t the only place that studies space that is no longer open. Among others, the Jodrell Bank Star-Watching-Place, ALMA, and the ESO have all either closed or working on shutting down, again so that the people who work there can stay safe. Now, people who study space are working from home when possible - like all of us here! This means that space news might not be quite as exciting as usual for the next few weeks or months, but don’t worry - we’ve still found some for you today!

While we here at the Jodcast usually use space machines to look out into space rather than back down at Earth, our space watching-machines are also very important to understand our own world. These space machines, which go around in circles a hundred times higher than Earth’s highest mountains, give us a special view of the Earth and are seeing interesting things since all the people are having to stay inside. Our space machines are seeing up to half less of some kinds of bad tiny matter in the air over large parts of the world. Images from near-Earth space machines also show much less travel and visitor interest at places where people board moving machines. Since these kinds of bad tiny air matter are mostly made by our moving machines and buildings where human goods are made, it is a sign that people’s doings are lowering across the world. It is interesting to know how much these changes can be seen from space, although the situation causing it is clearly very bad.

We hope all of you listening are taking care of yourself and each other. While many of us at the Jodcast can continue working from our homes, our thoughts are with everyone who is alone or in trouble at this time. Until next time!

---

First, some news about what's been happening at JBCA. Since we started making this month's show, the University of Manchester made the decision to shut down al of its buildings for the safety of students and staff, so we can no longer get access to JBCA. Because of this, the Jodcast will sound a little different for the foreseeable future - because we can't get into our studio - and might not have all the usual sections as a result. Even though we might not sound as good as normal, though, we'll make our best effort to keep the show going out as usual.

JBCA isn't the only scientific building that's shut because of recent events. Amongst others, the Jodrell Bank Observatory, ALMA, and the ESO have all either closed or are in the process of shutting down, again for the safety of their staff. Now, astronomers from these places are working from home when possible, like us at the Jodcast. This means that astronomy news might be quite quiet for the next few weeks or months, but don't worry - we've still found some for you today!

While we here at the Jodcast usually use our instruments to look out into space rather than back down at Earth, these instruments are also important for our understanding of our own world. Satellites give us a unique view of the Earth and are seeing some interesting consequences of people having to stay inside. Satellites have recently observed up to a fifty percent decline in air pollution over large parts of the world. Images from near-Earth satellites are also showing much less travel and visitor interest in mass transit, particularly airports. Since air pollution is largely caused by transport and factory emissions, it's a sign that these activities are reducing across the world. It's interesting that we can identify these changes from space, although the situation causing it to occur is clearly negative.

We hope all of our listeners are taking care of yourselves and each other. While many of us at the Jodcast can continue working from our homes, our thoughts are with everyone who is alone or struggling at this time. Until next time!

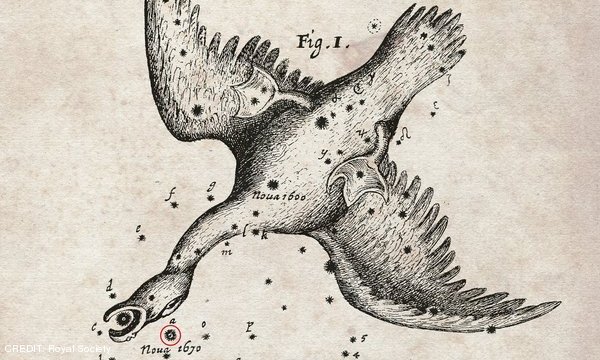

Asking Stewart Eyres Questions

Dr. Stewart Eyres talks about his work studying CK Vulpeculae, which was found in the 1980s to be a star that blew up a long time ago named Vul 1670, which was seen to become brighter in 1670 by star-studiers of the time. First studied in the ‘80s to find out whether normal-class and small-class stars-that-blew-up ever turn into one another, he talks about its history (part of which is the first piece of writing about it, in Latin, a picture from which is our cover image this month – see it for yourself here), why it’s now quite certain it’s a small-class star-that-blew-up, and his studies on what kinds of matter it was formed from. He also talks about how the time needed to be certain about a new sighting has changed over the years, and how searches have allowed stars-that-blew-up to be found earlier than ever before.

Note from the person who put the show up: Because of a problem with our sound-to-computer machines, the goodness of sound of this talk is not as good as we'd like. However, we thought it was too interesting a talk to not use it at all, and our people who make words sound good have done their best to make sure Dr. Eyres can be heard. We hope it's still good to listen to for you all.

---

Dr. Stewart Eyres talks about his work studying CK Vulpeculae, which was identified in the 1980s to be a historic nova named Vul 1670, which was observed to brighten to third magnitude in 1670 by astronomers of the time. Initially studied in the ‘80s to investigate whether transitions between classical and dwarf novae ever occur, he discusses its history (including the original Latin publication about its observation, a diagram from which is our cover image this month – see it for yourself here), why it’s now fairly certain it’s a dwarf nova, and his recent studies on what objects it was formed from. He also talks about how the time required to confirm a new sighting has changed over the years, and how modern surveys have allowed novae to be detected earlier than ever before.

Producer's note: Due to an error with our recording equipment, the quality of this interview is unfortunately not to as high a standard as we'd like. However, we thought it was too interesting a subject to not use it at all, and our editors have done their best to make sure Dr. Eyres is audible. We hope it's still enjoyable for our listeners.

The Night Sky

Above The World's Middle Line

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the night sky above the world's middle line during Month 4 2020.

The Planets

- As April begins, Jupiter rises some three and a half hours before the Sun shining at magnitude -2.1. It then follows Mars and precedes Saturn, just above Mars, into the pre-dawn sky. During the month it brightens to magnitude -2.3 whilst its angular size increases from 37.0 to 40.6 arc seconds. A low south-eastern horizon will be needed and our views of the giant planet and its Galilean moons will be somewhat hindered by the depth of atmosphere through which it will be observed.

- As April begins, Saturn rises at 05:33 UT, 20 minutes after Jupiter, and by its end at 02:50 UT whilst its magnitude increases slightly from +0.7 to +0.6 whilst its angular size increases from 16.1 to 16.9 arc seconds. Saturn reaches ‘quadrature', 90 degrees in angle from the Sun, on April 21st enhancing the three-dimensionality of its globe and rings. At 21 degrees, the rings are slightly less tilted to the line of sight than they have been for some time. Sadly, its low elevation before sunrise will somewhat limit our views of this most beautiful planet.

- Mercury is lost in the Sun's glare this month, so cannot be observed.

- Mars can be seen towards the southeast in the pre-dawn sky at the start of the month. It then rises at ~04:48am and will be best seen at around 6am having an elevation of ~8 degrees. It will then have a magnitude of +0.78 and a 6.4 arc second, salmon-pink, disk and lies just inside Capricornus. By month's end it will have moved over to the east of Capricornus and its magnitude will have increased to +0.43 and it angular size to 7.6 arc seconds. Having started the month just below Saturn, it rapidly leaves Saturn and Jupiter as it crosses Capricornus.

- Venus is still dominating the south-western twilight sky. It reached greatest elongation east from the Sun on the 24th March but is still near its highest possible altitude and April is still one of the very best months to observe it in its 8 year cycle of apparitions. As April begins, it will then have an elevation of ~39 degrees at sunset - about the highest elevation it can ever achieve! During the month its angular size increases from 25.5 to 38.2 arc seconds but, at the same time, it phase (the percentage of the disk illuminated) decreases from 47% to 26% and so the brightness only increases slightly from -4.5 to -4.7 magnitudes. This is about the brightest that Venus ever gets!

Highlights of the Month

- April 1st - before dawn: Jupiter, Saturn and Mars. Before dawn on the first of the month, Mars will be seen to lie just below Saturn with Jupiter over to their right.

- April 3rd - evening: Venus within the Pleiades Cluster. After sunset on the 3rd of April, if clear, Venus will be seen to lie just to the left of Merope within the Pleiades Cluster. A great photographic opportunity!

- April 15th - before dawn: the Moon joins three planets. Before dawn on the 15th of April, the Moon, just after third quarter, lies below a lineup of Mars, Saturn and Jupiter.

- April 25th - after sunset: A very thin crescent Moon lies between the Hyades and Pleiades Clusters. If clear after sunset on the 25th of the month, a very thin crescent moon will be seen to lie between the Hyades and Pleiades Clusters in Taurus. It may be possible to spot the 'Old Moon in the New Moon's arms' due to earthshine. Binoculars may well be needed, but please do not use them until after the Sun has set.

Below The World's Middle Line

Haritina Mogosanu and Samuel Leske from the Carter Science Centre in New Zealand speaks about the night sky below the world's middle line during Month 4 2020.

In these very strange times, as we find ourselves locked inside our homes, we might have some ideas as to what to do with the April night sky. Hopefully you’ll be able to actually get out of your house and take your telescope somewhere else to have a look at the night sky.April is a month of action in astronomy and stargazing! Global Astronomy Month (GAM) is organised each April by Astronomers Without Borders and the International Dark Sky Week is also in April, this year from Sunday, April 19 until Sunday, April 26!

Planets- Look for Venus in the evening sky, where it is shining very bright. You can try to see it during daytime if your eyesight is good and you know exactly where to look.

- Look for Jupiter after midnight at the beginning of the month, and after 10:30 PM towards the end of it - thanks to daylight saving as well as Earth’s revolution around the Sun that among other things makes stars rise 4 minutes earlier every day. Try to spot Saturn and Mars about half an hour after Jupiter.

- Morning Owls can still enjoy Mercury as well as a beautiful arch of planets stretching across the sky and are welcome to tell us if it is worth waking up that early to see them. Sadly Mercury will disappear in the twilight of the rising Sun at the end of the month.

Stars

- Try to see the brightest stars in the sky - now is the time (as it was last month but we can still enjoy these in April). They are Sirius, the dog star, Canopus the cat star and Alpha Centauri, our closest neighbour 41.3 trillion kilometres away (so in the safe zone). Although, technically Sirius and Alpha Centauri are double stars, so then are they the three brightest stars or the five brightest stars?

Galaxies

- Milky Way - the obvious choice is brightest towards Crux. The centre of the galaxy rises around 10PM. In it, Scorpius is now here called Manaia ki Te Rangi, the guardian of the sky, and if you're into jewelry, you’ll see that it looks like a manaia made of green stone - pounamu. It’s a beautiful name for Scorpius and is great that the asterism can look like so many things, including a scorpion - which here in New Zealand don’t exist.

- Other visible galaxies are the Magellanic Clouds. Look for these in the Southern part of the sky, obviously, the part that we call circumpolar from here as the stars there never set and never rise but move around the celestial south pole in circles. Usually any star above declination -60 classifies as circumpolar from here.

- There are a whole bunch of amazing galaxies around Leo at this time of year. For our northern hemisphere listeners, Leo in the southern hemisphere is upside down from what you’re used to. The most amazing of the group of galaxies is the Leo triplet, which is M66, M65 and NGC 3628, and it’s really amazing to see three of them in the eyepiece. If you’ve got a big enough telescope, you can always go a little better, up the sky to NGC 3593 and then a little bit further away to NGC 3596 which are two nice galaxies too. Also a little bit above Leo, there’s another bunch of galaxies, Messier objects M95, M96, and M105, and in fact round M105 there’s another couple of galaxies, NGC 3389 and NGC 3384 - they’re all quite easy to see. If you’ve got a big telescope, you can also have a look for four other galaxies that are closer to Leo than the three I just mentioned: NGC 3338, NGC 3367, NGC 3377 and NGC 3412. They are all pretty easy to find as well. NGC 3367, if you can catch that one, is a hundred and fifty million light years away, which is staggering.

- Closer to the horizon, there’s all the galaxies that are around Virgo. They’re probably still a bit low for us, but by April if we stay up late enough there will be a beautiful bunch of galaxies to have a look through. That’s one of the great groups of galaxies that we share with the northern sky.

- Also, one of the classics for us is the Sombrero Galaxy, absolutely magic to look through on the telescope. Then, there’s M83, which is the big spiral that we see down here in the southern hemisphere. There’s Centaurus A, also known as the Hamburger Galaxy, and there’s another great galaxy that we quite like looking at as well - it’s NGC 4945, which is just above Omega Centauri, between Omega Centauri and the Southern Cross.

Binocular objects

- Omega Centauri is a nice big globular cluster, really easy to see and you can totally spot that.

- Now, if you’ve got a nice dark sky you’ll also be able to see M83 pretty easily in binoculars, so that’s definitely worth checking out. There’s not many galaxies you can see in binoculars, but M83 is one of them, and in summer you can see Sculptor, so now we’re sort of getting into the colder months M83 dominates.

- Then there are the larger clusters, the Southern Pleiades you can look at, which is pretty amazing in the binoculars. Omicron Valorum is high in the sky, as is NGC 2516, the Southern Beehive, and of course if you’re looking at the Southern Beehive you probably also want to look at the other Beehive, M44 in Cancer, which is also an absolutely wonderful binocular object as well. M42, the Eta Carina nebula is always great, and the Wishing Well cluster stands out really well in binoculars as well. 47 Tucanae is the other really nice globular cluster to have a look at.

- Of course what you can do as well is just lie on the ground with your binoculars and just browse around the Large Magellanic cloud. You’ll see the Tarantula nebula, and you might see a whole bunch of fuzzy-looking stars, which will be the big collection of globular clusters and other open clusters they have in that galaxy. So well worth having a look there, especially if you have a decent high-powered pair of binoculars, but still quite cool on small binoculars as well.

So, from here from New Zealand, we wish you clear skies so that you can always see the stars, and stay safe - stay inside, keep your two metre distance from people, and don’t get sick. Clear skies, everyone, and let’s hear each other healthy next month.

Month 4 Special: Explaining What We All Do

Crispin Agar

I work on stars that have reached the last parts of their lives. At this point, they have gone through the stage where they blow up, and what is left is a very small, heavy piece that is the size of a city but still is heavier than our sun. These stars are the heaviest, smallest things in space - one step behind a black hole! They turn round very fast and because they also try to pull metal towards them, this makes them become a machine that gives out lots of light from the top and bottom which we can only see with big radios. As the stars turn round quickly, the light flashes on and off. I look at the shape the light makes as the star goes round, and which way it points on the sky, and this tells me how the star makes the light.

I work on pulsars, which are the remnants of stars that have exploded in supernovae. They are incredibly dense, with a mass of 1.4 times that of our sun but a diameter of only 20 kilometres. They are probably the densest objects in the universe, excluding black holes. Despite their incredible mass and size they spin incredibly rapidly, with the shortest known rotational period being around one millisecond. As they are highly magnetic (10^14 gauss), their rotation induces strong electric fields which in turn leads to electron-positron pairs being formed around their magnetic poles. Bunches of these charged particles move along the field lines and the star emits coherent beams of radio waves in a "lighthouse" effect, appearing to pulse on and off as the beams pass Earth. I study the polarisation of the radio beams and their structure and time variability, which provides an insight into the underlying radio emission mechanisms in these extreme astrophysical laboratories.

Tiaan Bezuidenhout

Some lights that are up in the sky are always there, never changing. Others can only be seen now and then, or even just once and never again. To find these lights you need a couple of things at once: first, a big old thing to catch the light (or even better, many of them!); second, a real strong computer to look at the light; and third, some well thought-out orders to tell the computer what to do so as to find the flashing lights. My team and I am working with a set of light-catching things in my home land. We are writing the orders to let a computer there find those flashing lights in the sky in real time. Once we have found enough of them we can try to figure out what in the world is making them. But, I'm sad to say, we have not seen any flashes yet. Really what I've learned so far is that sometimes the sky and Lady Chance work together to kill your dreams. Still, I have hope that our day will come soon, and on that day I will be very happy.

I work on strategies for finding single pulses from fast radio transients. I'm part of a group working with the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa to look for fast transients, especially Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs). We've created a data pipeline that does single pulse searches in real time commensally with other projects. That means that as others are using the telescope for their own purposes, we are continually intercepting the voltage data from the dishes and combing the data for signals from fast transient sources. My role is working with the single-pulse searching software to distinguish real pulses from noise or interference, as well as following up on interesting sources that we find, especially localising them to their exact position on the sky.

Jake Staberg Morgan

My work is all about worlds which go around stars other than our Sun. We've found quite a few of them so far, and they come in all the types you can imagine. We haven't found any other worlds with life yet, but we would very much like to. To find these worlds, we watch their star as the world goes across it, which makes the star a little bit less bright. From this, we can tell how big the world is, how quickly it goes around its star and even what it might be made of. The ones I look at are big and very close to their stars, going around in a few days or even less. Because they are so close in, they're very hot, and lots of them don't turn round in the normal way. Instead, one side always faces the star and is very hot, while the other side is always dark.

The people that look at these worlds have made a problem – because we're finding so many new worlds from space, we don't have enough time, money, people or other stuff and things to look at them all. It would be too much work to get people to go through all the worlds in the group and pick out the good ones, so I have made a computer do it for us. We have to pick some important numbers for each world – we like big worlds around bright stars, because they're easier for us to see. We also like hot worlds, because that makes them bigger, and we like worlds that go around their stars quickly, because that means we have more times to look at them.

Using these important numbers, we make a big group of all the worlds we know and give each one a number that says how good they are to look at. We can then pick the best ones and give them to people to go and look at them, to try and work out what they’re made of. That way, we won’t have to go through the group by hand, and it will still work as the group gets bigger.

I'm writing about all of this at the moment, in what's called a sad book. We each have to write a sad book at the end of our time here, with lots of words and pictures. Once the book is done, some big space people will come and ask me lots of questions about all the things I did. If they like what I've done, I will be allowed to call myself a doctor and wear important clothes.

My research is focused on exoplanets, orbiting stars other than our Sun. The population stands at 4,200 and growing, and includes Earth-sized planets to extreme hot Jupiter objects. As of yet, we have not found any other planets harbouring life, but this is certainly one of the ultimate goals of the field. I work with hot Jupiters discovered via the transit method – as they cross the face of their host star, they block a small fraction of the total light, which we can detect with telescopes. From this, we can recover the planet radius and orbital period, as well as probe its atmosphere via transmission spectroscopy. These planets are strongly irradiated by their host stars due to their close-in orbits, which also often causes them to become tidally locked, with permanent day and night sides.

With the success of missions like TESS, exoplanet astronomers have created a problem for themselves – with anything up to 10,000 new planets expected, the community will not have enough telescope time, staff or money to follow up every planet. Manual selection of targets will also become impractical, so I have developed a software pipeline to make these selections for us. This is based around a decision metric, which ranks a list of planets by assigning a score to each, depending on how strong their atmospheric signal is expected to be. The metric rewards large worlds in orbit around bright stars, as these are easier to observe, and rewards hot planets for the same reason. Short-period objects are also preferred, as their more frequent transits give us more opportunities to take data.

Using the metric, the best targets can be selected and assigned to telescopes for transmission photometry/spectroscopy observations. This solution means manual selection is no longer needed, and it will also scale as more planets are found.

I’m currently writing up my thesis, which stands at 236 pages so far. Once this is done, I will have to pass my viva, where examiners will read my thesis and ask me lots of questions about my work. If they are satisfied that it represents an original contribution to human knowledge, I will have earned the title of Doctor, and will get to wear a fancy hat for my graduation. Finnish doctors also earn the right to carry a sword, but Manchester doesn’t do this to my knowledge.

Lizzy Lee

Stars are found in groups in space, called 'star-groups'. These star-groups are often found in larger groups, called 'star-group-groups'. These star-group-groups are very big and also have a lot of dust in them. This dust is very very very hot (as hot as the inside of the sun) and gives off light we can only see with special seeing things. We can also see this dust because it changes other light that passes through it. I will now give some more words about this light.

In the very beginning, after the big loud noise, light could not be seen, because light was changed and eaten quickly by everything else. This was because there was a lot of things, in not very much space. Then, as things moved away from one another, the light could move around everywhere. Some of this light can still be seen today, although it is very old. This is called the 'space small light behind all things' and can actually be seen in the white noise in televisions and radios.

Since this light is everywhere, it has passed through many star-group-groups, and been changed in special ways that we can see, this change is called the Sunyaev-Zeldovich change. I study how changes in these star-group-groups would change what we would see so we can learn more about the star-group-groups.

In space, stars are found in galaxies, and galaxies are often found in larger groups called galaxy clusters. These galaxies clusters are extremely large and contain huge amounts of dust (in fact they have about 9x as much dust than galaxies by mass). This dust is very very hot (>=1keV or about as hot as the inside of the sun) which emits spontaneously in X-rays. However, we can also see the effects the dust has on light passing through it.

So, we must discuss the light that passes through these clusters. In the very beginning of the Universe, after the Big Bang, light couldn’t be seen in the universe, because it was absorbed almost as soon as it was emitted on account of the exceedingly high density in the early universe. However, as the Universe expanded, and the density and temperature of the Universe fell, light could pass freely without being reabsorbed. This event released light that can still be seen today, although it is now so old that it is both dim and the light itself has been shifted in frequency to be microwave radiation. This is called the Cosmic Microwave Background, and can be see as a large portion of the static seen in untuned televisions and radios.

Since this radiation is everywhere, some of it has passed through galaxy clusters before it has reached us. This leads to a characteristic distortion called the Sunyaev-Zeldovich effect. I study how changes in galaxy clusters would lead to changes in the distortion we would observe, so we can learn more about these galaxy clusters.

Fiona Porter

Stars are usually found in large groups in space, called star-groups. I study radio star-groups called Faranoff-Riley star-groups, which are broken into two classes: class one and class two. We don’t understand the reason why they give off radio waves in different ways, in part because we don't have many of them to study. My work hopes to create some machine learning computer-plans to be able to find Faranoff-Riley star-groups without getting them confused with other kinds of star-group.

Finding Faranoff-Riley star-groups can take lots of time at the moment, as all radio-images need to be checked in person by people who study space. This needs the space-studier to know which types of repeated shapes are expected in which kind of star-group, and can take quite a lot of time for each image. If computer-plans can be used to check new radio-images in the future as soon as they're made, we could find large numbers of these star-groups very quickly.

I’m working with a kind of machine learning called brain-like maps-of-machine-thoughts, which are trained to find the star-groups by being shown as many training images as possible. They pass the training images through picture-changers, then guess what class of star-group is in each image. They’re then told if they were right, and start to learn what repeated shapes are expected to appear in each class using the information they get from their picture-changers. Once they’ve finished training, a map-of-machine-thoughts like this can check hundreds of images every second.

I study radio galaxies called Faranoff-Riley galaxies, which are split into two types: type I and type II. We don’t understand the mechanism behind how they emit currently, partially because a relatively small number of them are known of. My work aims to develop some machine learning algorithms to be able to accurately identify Faranoff-Riley galaxies.

Identifying Faranoff-Riley galaxies correctly can take large amounts of time at the moment, as all data needs to be checked manually by astronomers. This needs the astronomer to have practice recognising which features are expected in which type of galaxy, and can be quite time-consuming. If algorithms can be used to automatically check new data in the future, we could detect large numbers of these galaxies very quickly.

I’m working with a type of machine learning called Bayesian Convolutional Neural Networks (BCNNs), which are trained to identify the galaxies by being shown as many training images as possible. They pass the training images through filters, then predict what type of galaxy is in each image. They’re then told if they were correct, and start to learn what features are associated with each class based on the information they get from their filters. Once they’re fully trained, a neural network like this can classify hundreds of images per second.

Show Credits

| News: | Luke Hart |

| Interview: | Stewart Eyres and Fiona Porter |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and Haritina Mogosanu |

| People who speak through the whole show: | Fiona Porter, Lizzy Lee, and Tiaan Bezuidenhout |

| People who make our words sound good: | Joseph Winnicki, Lizzy Lee, and Adam Avison |

| Voice between parts: | Tess Jaffe |

| Computer place where our show lives: | Fiona Porter and Stuart Lowe |

| Person who put the show where you can hear it: | Fiona Porter |

| Cover art: | This chart of the position of a nova (marked in red) that appeared in the year 1670 was recorded by the famous astronomer Hevelius and was published by the Royal Society in England in their journal Philosophical Transactions. CREDIT: Royal Society |