In the show this time, we talk to Thomas Tauris about compact stars, pulsars and outreach, Ian Evans rounds up the latest news, and we find out what we can see in the June night sky from Ian Morison and Haritina Mogosanu.

The News

Have you ever wanted to sneeze but it didn't happen? Your whole body readies itself for the coming explosion. You make the "Ah, Ah, Ah" sound but then, nothing. No sneeze. Just you with a surprised and disappointed look. Something similar has happened, on a slightly different scale to N6946-BH1, a star in the fireworks galaxy, so called for the large number of supernova of which it is the source.

The life of stars is well understood. At the end of their lives, large stars with masses in excess of three solar masses swell in size to super massive red giants when they switch from hydrogen to helium fusion. When their stocks of helium start to run out they collapse. The bounce back from the collapse is a supernova, one of the most spectacular events that astronomers can witness.

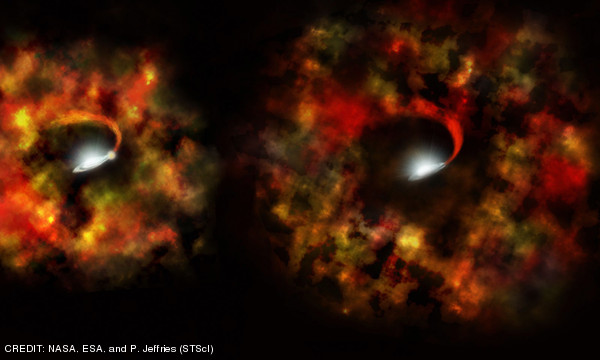

N6946-BH1 seemed to be following the pattern. In 2009 astronomers from Ohio State University saw the star brightness increase. This they thought was a precursor to the star going supernova. But then the massive star failed to explode. In fact it disappeared from view. The team from Ohio state, working alongside astronomers from the University of Oklahoma, searched for the star using the Hubble and Spritzer space telescopes. They failed to find any supernova or remnant. In fact, the star had become invisible in the visual band, and was only 5000 times as bright as the sun in infrared radiation. Initial theories were that the supernova had been obscured by dust ejected from the star but this did not stand up to observations. Ohio State's Professor Christopher Kochanek's new theory is that super massive stars simply fail to go to supernova and instead collapse to a black hole. He and his team suggests that N6946-BH1 formed a dense core surrounded by an envelope of gas, mostly hydrogen. This envelope extended out to a similar size as the orbit of Jupiter. Owing to its size the envelope was only weakly gravitationally attached to the core. When the core collapsed the shock wave that passed through the envelope was weak. Certainly not up to the strength needed for a supernova.

It is possible that there is an optimum size for a star to form a supernova. Too small, like our Sun, and the star forms a white dwarf. Too big and the stars core collapses to form a black hole without triggering a supernova. As Scott Adams, one of the lead authors on the paper indicates, 10 to 30 percent of massive stars die as failed supernovae. So there are fewer observed supernovae than should be occurring if all massive stars die that way.

Further observation in the x-ray and possibly gravitational waves using the LIGO observatory could give us more information on the deaths of these super massive stars.

Fast radio bursts have been causing a stir in the radio astronomy community in the last few years. Professor Duncan Lorimer based at the West Virginia University and before then, Manchester University spent the summer of 2006 reviewing data from the Parkes Radio Observatory. He found a millisecond pulse recorded in 2001. Initially it was thought that the pulse had a terrestrial origin, not unlike the signal that the Greenbank telescope discovered only for it to be the microwave oven in the observatory cafeteria. Further examination of the data uncovered more Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs). To date, 24 FRBs have been observed. That they did not seem to be confined to the galactic plane suggested that these had an extragalactic origin. If that is the case then the source of these FRBs must be very powerful. The discovery of FRB 121102 in 2012 by multiple telescopes strongly suggests the source for that burst being a dwarf galaxy 3 billion light years from the Earth. This FRB also repeated first after 50 hours then, sometime later saw pulse just over 20 seconds apart. This raises questions over the source of these extremely powerful bursts of energy.

With such a small set of data to work with the causes of these FRBs is open to multiple explanations ranging from merging black holes to extraterrestrial civilisations. What is needed is a far greater dataset. Some telescopes such as BINGO, the Baryon Acoustic Oscillation from Integrated Neutral Gas Observations telescope, CHIME, the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment and their Chinese equivalent Tianlai will spend a lot of time observing the sky at frequencies around 1 Gigahertz. They will cover a large area of the sky and so should pick up more examples of FRBs. As of now Chime and Tianlai are both in their early stages of operation and BINGO is still on the drawing boards. What could be used in the meantime?

Professor Mike Garrett, director of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics suggests expanding the eMerlin system. The eMerlin system includes the two large dishes at Jodrell Bank as well as five other dishes extending out to Cambridge. Professor Garrett suggests that adding extra dishes including the large satellite communication dish at Goonhilly would increase the capacity of eMerlin to spot and, more importantly get precise locations for the sources. If the FRBs are associated with galactic centres then super massive black holes could provide a mechanism. If they are associated with the edges of galaxies then some mechanism associated with new stars could be the answer.

Until we gather more data all we can do is speculate on the source of these enigmatic bursts of radio noise.

While many amateur astronomers are active in observing in visible light, there are far fewer observing at radio wavelengths. Amateurs, some working as part of Project Jove have, over the years, been able to use basic receivers to pick up radio signals from Jupiter which is a bright radio source in the sky. This is changing with the introduction of Software defined radios. These radios use computers to do all the heavy lifting in tuning and processing the signal. It was discovered that some inexpensive USB TV tuners contained chipsets that would allow then to be used at frequencies far outside the TV bands. The R820T chipset can receive radio frequencies continuously from 30 MHz up to 2 GHz. While these have many terrestrial uses such as monitoring ADSB signals from commercial aircraft and picking up weather images from NOAA satellites it is the area of radio astronomy that offers opportunities to amateur astronomers.

Mario Cannistrà on the hackster.io website shows how to build an inexpensive updated version of Project Jove's Jupiter receiver using an SDR, an up-converter to take the 20 Mhz signal from Jupiter above the 30 Mhz lower limit for the SDR, a low noise amplifier and a raspberry pi computer. For less than 100 pounds you can record radio signals from Jupiter.

More adventurous amateurs are picking up signals from much farther afield. The R820T SDR works well at 1420 MHz which is where you can find the hydrogen emission line. A satellite dish with a home built antenna built around a tin can is sufficient to pick up the hydrogen emission for the milky way along with the red and blue Doppler shifted lines from the spiral arms.

Other sources are more of a challenge. An SDR is not very sensitive so a target with a large signal to noise ratio is preferred. Steve Olney administrator of the Neutron Star Group has reported the successful detection of pulsars by astronomers using SDRs. This is not for the faint hearted. Hannes Fasching based in Austria has detected pulsars using a 7.3 m dish while Mario Natali Based in Italy Mario uses a 5 m dish. If those dishes are a little too big for your back garden then Steve Olney has finally been able make his own confirmed pulsar detection using a 42-element circularly polarized Yagi antenna tuned for 436 MHz and an RTL-SDR. A 42 element Yagi is a long antenna and his setup has the antenna pointing vertically up. His target is the Vela pulsar which happens to pass almost directly overhead at his location.

The signal from the pulsar has to be recorded over several hours. It is then subjected to a process called epoch folding in which short time interval are superimposed over each other. As the pulsar is extremely regular if the correct period is chosen then the repeated signal should emerge. This technique runs the risk of identifying terrestrial sources with a regular period so Steve has to observe the sky when the pulsar is not in view. The lack of a signal suggests a successful detection.

The fact that relatively inexpensive equipment is able to make valid observations of radio sources suggest that this growing field of amateur astronomy will be making important contributions in the future.

- Jupiter - Now two months after opposition, Jupiter still dominates the late evening sky shining in the south to southwest after nightfall. It sets about 3 am BST as June begins and by about 1 am at its end. As the month progresses its brightness falls from -2.3 to -2 .0 magnitudes as its angular size falls from 41 to 37 arc seconds. It lies in Virgo some 11 degrees to the west of Spica, Alpha Virginis, and halts its westwards retrograde motion on the 11th as it begins its initially slow eastwards march back towards Spica. It will pass Spica on September 11th on its journey towards the lower parts of the ecliptic. Next year it will only reach an elevation of some 25 degrees when due south and, in the following two years, just 18 degrees before it moves back towards the more northerly parts of the ecliptic. Even so, with a small telescope one should easily be able to see the equatorial bands in the atmosphere, sometimes the Great Red Spot and up to four of the Gallilean moons as they weave their way around it.

- Saturn - Saturn comes into opposition on June 11th and so, then, will be at its highest elevation due south at around 1 am BST and will be visible throughout the short night. It shines at magnitude 0.1 all month and has an angular size of 18.3 arc seconds. With an angle of 26.5 degrees inclination to the line of sight the rings are virtually as open as they ever can be. It is sad that Saturn, now lying in the southern part of Ophiuchus between Sagittarius and Scorpius, only reaches an elevation of ~17 degrees above the horizon when due south so hindering our view of this most beautiful planet. If imaging Saturn (or Jupiter), Registax 6 has a tool to align the red, green and blue colour images to largely remove atmospheric dispersion from the image. At somewhat over £100 one can purchase the ZWO atmospheric dispersion corrector which uses two, contra rotating, prisms to carry out an even better correction.

- Mercury - Mercury is lost in the glare of the Sun for most of the month before it makes a modest evening apparition in July. It might just be spotted with binoculars very low in the west after sunset at the very end of the month. But please do not use them until after the Sun has set.

- Mars - Following a two year long apparition, Mars finally slips into the Sun's glare in the first week of June when its salmon-pink disk might just be picked out in the west-northwest.

- Venus - Venus is visible in the east before dawn this month reaching its greatest elongation (46 degrees west of the Sun) on the 3rd of June. It magnitude dims slightly during the month from -4.5 to -4.2 as its angular diameter shrinks from ~24 to 18 arc seconds. However, at the same time, its phase increases from 48 to 62 percent which explains why the magnitude does not drop too much. Even though it will be moving back towards the Sun, as the angle of the ecliptic to the horizon increases at this time of the year, it elevation before sunrise will continue to increase until August.

- Introduction

Kia ora and welcome to the June Jodcast from Space Place at Carter Observatory in Wellington, New Zealand.

This month, we reach our winter solstice here in the southern hemisphere, when the south pole of the Earth is at its greatest tilt away from the Sun. This means that the Sun appears much lower in the sky, our days are shorter and colder, and our nights are longer.

This year the solstice falls on the 21st June NZST. Whilst always around this time, the actual date of the winter solstice can sometimes fall on the 22nd. This is because it takes the Earth approximately 365 and a quarter days to go around the Sun, but we don't count that extra quarter day in our calendars every year, we save them up for a leap year. So the timing of the solstice slips around 6 hours later each year until we add an extra day and it jumps back to the beginning again.

The word solstice means "Sun stopped" or "Sun still", because the Sun rises and sets at it most northerly points of the year. As we move back towards the summer, the Sun will gradually rise and set further and further south until it stops again at the summer solstice in December, and begins the long journey back north.

This month in the news: the supernova that wasn't, the search for Fast Radio bursts continues, and the amateur astronomers moving into radio astronomy.

Interview with Thomas Tauris

Professor Thomas Tauris is from the Astronomical Institute, University of Bonn, and Max-Planck-Institute for Radio Astronomy Germany. His research interests include Compact stars, binary evolution, pulsars, SNe, gravitational waves and Population Synthesis. Prof Thomas has a vast teaching experience and intersts towards science outreach. He has also written a popular science book on astronomy (in Danish), published number of newspaper articles and enjoy giving talks about the Universe to anyone who is interested in listening.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during June 2017.

The Planets

Highlights

Early June - still worth viewing Jupiter. .The features seen in the Jovian atmosphere have been changing quite significantly over the last few years - for a while the South Equatorial Belt vanished completely) but has now returned to its normal wide state.

June - The best month to observe Saturn. .The thing that makes Saturn stand out is, of course, its ring system. The two outermost rings, A and B, are separated by a gap called Cassini's Division which should be visible in a telescope of 4 or more inches aperture if seeing conditions are good. Lying within the B ring, but far less bright and difficult to spot, is the C or Crepe Ring. Due to the orientation of Saturn's rotation axis of 27 degrees with respect to the plane of the solar system, the orientation of the rings as seen by us changes as it orbits the Sun and twice each orbit they lie edge on to us and so can hardly be seen. This last happened in 2009 and they are now opening out, currently at an angle of 26.5 degrees to the line of sight. From this month the ring's orientation will begin to narrow until March 2025 when they will appear edge-on again.

June - Find the globular cluster in Hercules and spot the 'Double-double' in Lyra.Just to the left of the bright star Vega in Lyra is the multiple star system Epsilon Lyrae often called the double-double. With binoculars a binary star is seen but, when observed with a telescope, each of these two stars is revealed to be a double star - hence the name!

Late June: A very good time to spot Noctilucent Clouds! .Noctilucent clouds, also known as polar mesospheric clouds, are most commonly seen in the deep twilight towards the north from our latitude. They are the highest clouds in the atmosphere at heights of around 80 km or 50 miles. Normally too faint to be seen, they are visible when illuminated by sunlight from below the northern horizon whilst the lower parts of the atmosphere are in shadow. They are not fully understood and are increasing in frequency, brightness and extent; some think that this might be due to climate change! So on a clear dark night as light is draining from the north western sky long after sunset take a look towards the north and you might just spot them!

June 3rd - evening: The Moon and Jupiter.During the evening of the 3rd June, the waxing Moon will lie less than 2 degrees up and to the right of Jupiter.

8th/9th June - around midnight: Observe the Galilean Satellites. .If clear around midnight the 8th/9th, and using a small telescope, one could observe the 4 Gallilean Moons lined up on one side of the giant planet.

Night of June 15 to 16th when fully dark: The Lyrid Meteor Shower.The June Lyrid meteor shower reaches its peak on the night of the 15th/16th with a rate at the zenith of ~8 meteors per hour. This is not many and, as the Moon is close to third quarter it may be hard to spot one. The radiant is very close to the star Vega. Many more meteors were seen from the shower in the late 1960's but the peak hourly rate has dropped off markedly since then. If clear, it may still be worth aiming to see if you can spot one.

21st June - before dawn: Venus and a thin crescent Moon.Before dawn on the 22st, Venus will be seen some 4 degrees above a very thin waning crescent Moon.

Late June - around midnight: Observe Comet 2015 V2 (Johnson) .On the 12 June but, sadly, close to Full Moon, Comet Johnson is at perihelion lying at a distance of 1.64 AU from the Sun. On the 1st of June it will lie over to the left of Arcturus in Bootes but passes into Virgo on the 14th. In the latter part of the month with no moonlight to hinder our view, binoculars or a small telescope could be used to spot Comet Johnson as it move across Virgo. It is expected to reach magnitude +6 so should be easily visible with binoculars. The chart shows its position during the month.

June 3rd and 16th: The Alpine Valley.These are two good nights to observe an interesting feature on the Moon if you have a small telescope. Close to the terminator is the Appenine mountain chain that marks the edge of Mare Imbrium. Towards the upper end you should see the cleft across them called the Alpine valley. It is about 7 miles wide and 79 miles long. As shown in the image a thin rill runs along its length which is quite a challenge to observe. Over the next two nights the dark crater Plato and the young crater Copernicus will come into view. This is a very interesting region of the Moon!

Southern Hemisphere

Claire Bretherton tells us what we can see in the southern hemisphere night sky during June 2017.

The Planets

Highlights

StarsWhilst the cold weather at this time of year may not be so welcome, the long, dark nights provide a perfect opportunity to observe our beautiful southern skies.

We are very lucky here in the southern hemisphere, that we have a perfect view towards the central bulge of our Milky Way galaxy, so it appears broader and brighter across our sky. The center lies towards the constellations of Sagittarius, the archer, and Scorpius, the Scorpion, which is now midway up our eastern evening skies. Scorpius is our winter constellation, and together with Sagittarius, a little below, will be dominating our skies over the next few months.

At the heart of the Scorpion is the bright orange tinged star Antares, a red supergiant with a radius nearly 900 times that of the Sun. The name Antares means "rival of Mars" because of its distinctive colour, which tells us that it is a cooler star, at around 3 and a half thousand degrees. Antares lies around 550ly away and is amongst the 20 brightest stars in the nighttime sky.

To the left of Antares is a line of stars now forming the Scorpion's claws, and further left still the faint zodiac constellation of Libra, the scales. Libra's two brightest stars form an almost vertical line in our evening sky, and have perhaps the best names of any I have seen, Zubenelgenubi and Zubeneschamali.

Zubenelgenubi, the higher of the two, is half way between Antares and Spica at a distance of around 77 light years. At magnitude 2.7 it enjoys the alpha designation, despite being slightly fainter than its beta counterpart below, probably because it lies just a third of a degree from the ecliptic.

Using binoculars you'll see that Zubenelgenubi is in fact a double star with two components separated by around 5400 AU (a little under 4' on the sky), and which appear to be co-moving through space. Strictly speaking, the name Zubenelgenubi now only refers to the brighter of the two. Both components are spectroscopic binary stars in their own right, and there may be also be a fifth component to the system, KU Librae, located 2.6 degrees away.

Below Alpha Librae is the slightly brighter Beta Librae, or Zubeneschamali, at magnitude 2.6, which lies 185 lightyears away. Zubeneschamali is a hot blue main sequence star some 130 times more luminous than the Sun, and with twice the surface temperature. Whilst stars of this type are often seen as white or bluish in colour, Zubeneschamali has often been described as greenish by observers, the only green star visible to the naked eye. Whilst theoretically this is not possible, scientists are still unsure why so many observers claim to see it this way.

ConstellationsWhilst today these stars are part of Libra, the names Zubenelgenubi and Zubeneschamali derive from the Arabic for the southern claw and northern claw of the scorpion, referring back to the ancient Greeks who saw these stars as part of the constellation of Scorpius.

The idea of scales or a balance can be traced back to the ancient Babylonians though, some 4,000 years ago, at a time when the northern hemisphere autumnal equinox (where the Sun crosses the equator from the northern to southern hemisphere) appeared in that part of the sky. The choice of scales likely relates to the balance between light and dark, with equal hours of day and night experienced at the equinox, as well as the change of seasons from summer to winter, and therefore hot to cold.

The romans revived the idea, seeing Libra as the Scales of Justice held by Astraea, the Starry Goddess, represented by the neighboring zodiac constellation of Virgo. Virgo is currently home to bright Jupiter, sat a little to the left of the constellations brightest star Spica, high in the northeast after dark.

Below Scorpius is our second evening planet, cream-coloured Saturn, shining at magnitude 0 this month. Saturn reaches opposition on the 15th, when it will be directly opposite the Sun in the sky and overhead at midnight. Saturn will also be at its closest to Earth around this time making it appear at its largest and brightest, although in practice any difference will be hard to spot with the naked eye. Do take a look through a small telescope if you get a chance though. This opposition its rings will be almost at maximum tilt, so should be a wonderful sight.

Here in New Zealand, we don't have Scorpions, so we see Scorpius as something a little more familiar in the Southern Pacific. To Maori this group of stars is known as Te Matau a Maui, the fishhook of Maui, which he used to pull a great fish out of the ocean that became the north island of New Zealand, te Ika a Maui. Antares is known as Rehua, and represents a drop of blood that Maui took from his nose to use as bait.

This constellation was an important aid for ancient pacific navigators as it travels directly overhead from our latitude. Once te Matau a Maui was right overhead it was simply a case of travelling east or west to find Aotearoa/New Zealand.

By just before sunrise Scorpius or Te Matau a Maui has moved to the west south western horizon, with the hook pointing upwards.

The morning skies at this time of year are particularly important here in New Zealand as this is the time we celebrate Matariki, or Maori New Year. The timing of this celebration is based on the heliacal rising of the small group of stars known as Matariki or the Pleiades.

Opposite Scorpius in the morning sky is his arch enemy, Orion the hunter, rising directly east, with the three bright stars of his belt lying along the horizon. These are also known as Tautoru here in New Zealand.

If you follow these stars along the horizon to the right they point to Sirius or Takurua, the brightest star in the night time sky. Follow them to the left and you first come to a v shape forming the head of Taurus the bull, with the bright star Aldebaran marking his eye, and then to Matariki rising in the east north east.

The Pleiades is, in fact, visible throughout most of the year, but is only known as Matariki around this time. It disappears from our evening skies around April each year before reappearing in the morning in early June. It is this reappearance, or heliacal rising, that tells us that the old year is coming to an end. The next new moon (or for some iwi the next full moon) marks the beginning of the New Year. This year the new moon falls on the 24th of June, and may be visible a day or two after this, so Matariki will officially be celebrated on the 25th of the month.

Maori mythologyIn Maori mythology Matariki, Tautoru, Takurua and Rehua form four pou, or pillars that hold Ranginui, the sky father, in the sky. Matariki supported one of Rangi's shoulders and marks the rising point of the Sun at the winter solstice. Takurua (Sirius) supports the other shoulder and is the closest bright star to the Sun's rising point at the summer solstice. These two stars represent the extent of the Sun's movement throughout the year.

Tautoru held Rangi's neck and marks the celestial equator which runs along the length of Ranginui's backbone. Poutu-te-rangi or the star Altair, marks the other end. Over in the west Rehua, or Antares, supports Ranginui's lower torso. A line drawn from Matariki to Rehua marks the ecliptic; the pathway of the Sun, Moon and planets through the sky.

These four pou form the basis of a celestial compass, a map of the night sky that was used to navigate the Pacific Ocean and bring our ancestors to Aotearoa. Today Matariki is a chance for all New Zealanders to unite in celebration of this great land we all call home: its a chance to reflect on the state of the planet we live on and the bounty that we receive from Mother Earth, to celebrate our shared history and to reflect on our very unique place in the Universe.

Nga mihi o Te Tau Hou ki a koutou katoa

Wishing you all a very Happy New Year from the team here at Space Place.

Odds and Ends

George is organizing a conference called Measuring Star Formation in the Radio, Millimetre, and Submillimetre. This is the first meeting in which George is taking the lead in organizing, and it will be held at the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics. The goal of the conference is to bring astronomers together from around the world to share ideas about the ways in which star formation rates can be measured in this part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Most of the discussion focused on other galaxies. More details are available from the meeting website.

It's well established that by the time the Universe was only 1.5 billion years old, some of the most massive galaxies had already formed. Yet, this poses the question - how did the billions of stars making up those galaxies formed so quickly? A team led by Roberto Decarli at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy have recently discovered a population of rapidly star-forming galaxies that may solve this riddle. These galaxies were found by accident when studying quasars at high-redshift. Using the ALMA telescope, the team found these neighbouring galaxies were forming more than 100 solar masses of stars per year, which may account for the massive galaxies we see in the early Universe.

With last year's slew of sexual harassment reports, gender bias and the efforts to make astronomy more inclusive are topical issues. A recent paper by Neven Caplar from ETH in Zurich has highlighted the gender bias in astronomical publications. They find that, whilst women are now first authors on 25% of astronomy papers, male first authors still receive more citations than their female colleagues. They estimate that if the gender bias did not exist, then based on the characteristics of papers in their sample, they would expect men to receive around 4% fewer citations than women.

Mystery flashes detected by the Earth-observing Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) were explained this month as reflections from high altitude ice particles in the atmosphere. These are known as 'glints' and hundreds had been detected by the DSCOVR and a number of other Earth observation satellites at nearly blinding brightnesses. A team led by Alexander Marshak of the NASA Goddard space flight centre has identified the source of the glints, their height in the atmosphere and pointed out that they could potentially be used for learning about distant expolanets.

Show Credits

| News: | Ian Evans |

| Interview: | Thomas Tauris with Prabu Thiagaraj and Tom Scragg |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and Haritina Mogosanu |

| Presenters: | George Bendo, Monique Henson and Ian Harrison |

| Editors: | Parvin Mansour, Claire Bretherton, Ian Evans, Tom Hillier, Francesca Pearce, Tom Scragg and Charlie Walker |

| Segment Voice: | Iain McDonald |

| Website: | Charlie Walker, Ian Harrison and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Charlie Walker, Ian Harrison |

| Cover art: | An artists impression of a red supergiant star immediately collapsing into a black hole in a failed supernova scenario. CREDIT: NASA, ESA, and P. Jeffries (STScI) |