In the show this time, we talk to Professor Mihalis Mathioudakis about solar magnetism, Ian Harrison rounds up the latest news, and we find out what we can see in the April night sky from Ian Morison and Haritina Mogosanu.

The News

This month in the news: FRBs repeat, FRBs are localised and Astro-H is named, but then lost.

Two stories this month have involved the mysterious but much discussed Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) -- short but loud radio signals which have been observed but not understood by astronomers since 2007. In the first paper, appearing online in the journal Nature on the 24th of February, a group of astronomers lead by Evan Keane of Swinburne University of Technology in Australia claimed to have localised the origin of an FRB in both sky position and distance.

Since the bursts were first described eight years ago, FRBs have remained elusive enough to generate fierce debate. The differing times of arrival of the different radio frequencies within each burst suggested they had travelled through large amounts of material. But was this diffuse material across intergalactic distances, or was it incredibly dense material within our own galaxy? What mechanism was capable of producing such large amounts of energy? And why were the bursts seen so frequenctly in some surveys, but so seldom in others?

In the work by Keane and collaborators, at least one of these questions appears to have been answered, with the association of an FRB with a host galaxy some 6 billion light years away, something which had not been possible with any of the seventeen previously known FRBs. After this burst was spotted by the Parkes radio telescope in New South Wales, only seconds after it had arrived at Earth, a wide variety of telescopes across the Southern hemisphere sprung into action in an attempt to identify another object whose varying brightness coincided with that of the FRB. Because of the large field of view of Parkes, it is difficult to place where exactly on the sky a signal detected there has come from, meaning it is standard practice for astronomers to look for light from the event producing the FRB at other wavelengths as soon as possible, as other telescopes are capable of more precise determinations of sky localisation. In the case of FRB 150418 this appears to have been successful, with data from the Australia Telescope Compact Array (or ATCA) finding a radio source in a similar direction which flickered and faded in the six days following the FRB detection. The optical Subaru telescope in Hawaii was then able to indetify a galaxy at the same position, and measure its distance via the redshifting of spectral lines. This apparent confirmation of FRBs as having an extra-galacitic origin caused much excitement, as it shows them to be some of the most energetic events known in the Universe. Loud FRBs spaced across the Universe could potentially be useful in cosmology for both measuring distances and, through the delay in the time of arrival of their different frequency components, measure the number of free electrons between us and the FRB, identifying a source of matter outside galaxies otherwise invisible to us (although it should be noted these electrons could not be dark matter).

However, the excitement was modulated by an almost immediate rebuttal of the finding. Peter Williams and Edo Berger, both of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, placed a short paper on the arXiv server for academic pre-prints two days after the discovery was announced, pointing out a potential mistake in the analysis. The two Harvard astronomers claimed that the problem lay in the statistics of the original paper and that there was a much higher probablility that the flickering radio source seen by ATCA and identified as the after-glow of the FRB was in fact the more normal variability of an unassociated Active Galactic Nucleus -- the emission from the hot dense matter around a black hole at the centre of a different galaxy. Whilst AGN are still extreme and intersting events, they are present and well-studied throughout the Universe and need not have anything to do with FRBs.

Reaction to this possiblity was mixed and will take some time to resolve. The most promising approach appears to be in further observing the proposed host galaxy over an extended period of time. If any sign is seen of an uptick in the brightness of the radio galaxy, this would be an almost certain sign that the observation by ATCA was of a distant supermassive black hole drawing in and super-heating ancient gas and dust -- interesting, but not an FRB!

Also in the news this month was another, more secure story about FRBs. This one relates to the observation of several FRBs as repeating, meaning they cannot originate in single cataclysmic events such as the explosions of supramassive neutron stars -- one of their prevoiusly proposed origins. By observing the aforementioned frequency dependent delay (known as dispersion measure or DM) of the arrival of FRBs at the Aricebo radio observatory in Puerto Rico, the group led by Laura Spitler of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany, showed that the properties and sky positions of ten bursts seen in the latter half of 2015 were consistent with those of both each other and another burst seen in 2012. These FRBs are also all consistent with being extragalactic -- all having dispersion measure three times greater than the maximum expected from any source in the Milky Way -- but none have the all important associated host galaxy or redshift to confirm this with certainty. The mere fact they appear to repeat is still a huge finding for FRB astronomy, placing sever constraints on their origin and increasing the chances that they can be localised by other instruments who know when to expect their eruptions. However, there does appear to be a downside. If FRBs repeat and are not single events, it means they are unlikely to be so-called 'standard candles' of set intrinsic brightness which can be used for measuring cosmological distances. The best standard candle known to astronomers -- the type 1a supernovae -- have proven invaluable in measuring the expansion of the Universe and helping us learn about the nature of Dark Energy, will have to remain the best for now.

And finally, a new X-ray satellite hit severe problems this month when it lost contact with it's controllers and apparently broke into several pieces in orbit. The satellite, belonging to the Japanese space agency JAXA, was previously known as ASTRO-H but was recently named Hitomi -- a tradtion for Japenese missions whereby they are not named until safely in orbit. Hitomi was scheduled to be contacted on March the 26th for continued shake-down and calibration before beginning taking science data later this year. However, Hitomi failed to report and observations appeared to point tosevere problems for the satellite. Tracking data showing orbital period against time for the 26th of March appears to show a sharp discontinuity, hinting at a violent event, as does the US Joint Space Operations Centre's report of five smaller objects orbiting along with the satellite and amateur astronomers reports of the spacecraft tumbling apparently out of control. It remains to be seen whether the incident is the result of an asteroid or other space debirs striking Hitomi, or whether a fault on the craft itself caused an explosion. Losing contact for a time with a satellite does not necessarily mean the mission cannot become highly successful; with both the XMM-Newton telescope and the New Horizons Pluto probe going dark for several days before coming back online. And, indeed, JAXA reported on the morning of the 29th of March that two fleeting communications had been made with Hitomi. The astronomy community will keep its fingers crossed, hoping that all is not lost and we do not have to wait for ESA's ATHENA X-ray telescope to be launched in 2030.

Interview with Professor Mihalis Mathioudakis

Mihalis Mathioudakis is a professor at Queen's University Belfast, where he works on the physics of cool stars and the Sun. In this interview, he tells us about his research on the solar chromosphere, and how it can impact a wide range of other fields. He talks about how observations of the chromosphere can tell us about the Sun's magnetic field, particularly with features such as magnetic bright points and Ellerman bombs. He also discusses how upcoming solar telescopes may lead to new discoveries, and the importance of ground-based observations of the Sun.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during April 2016.

Highlights of the month

April - still a great month to view Jupiter.

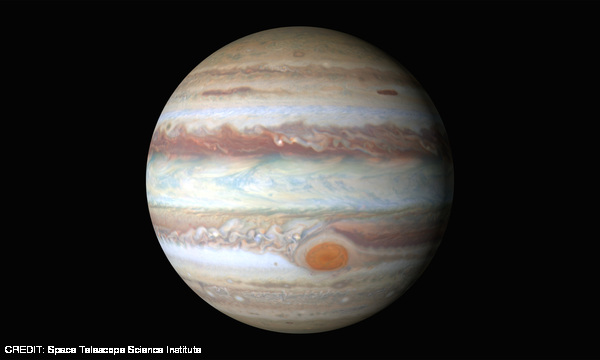

This is still a great month to observe Jupiter. It lies in the southern part of Leo, but still reaches an elevations of ~48 degrees when crossing the meridian during the evening. An interesting observation is that the Great Red Spot appears to be diminishing in size. At the beginning of the last century it spanned 40,000 km across but now appears to be only ~16,500 km across - less than half the size. It used to be said that 3 Earths could fit within it, but now it is only one. The shrinking rate appears to be accelerating and observations indicate that it is now reducing in size by ~580 miles per year. Will it eventually disappear?

The features seen in the Jovian atmosphere have been changing quite significantly over the last few years - for a while the South Equatorial Belt vanished completely but has now returned to its normal wide state.

April: Look for the Great Red Spot on Jupiter

The list below gives some of the best evening times during April to observe the Great Red Spot which should then lie on the central meridian of the planet.

- 1st - 23:47

- 4th - 21:16

- 6th - 22:54

- 9th - 20:24

- 11th - 22:02

- 13th - 23:41

- 16th - 21:10

- 18th - 22:49

- 20th - 21:03

- 21st - 20:18

- 23rd - 21:57

- 25th - 23:25

- 30th - 22:44

April 3rd - 22:00 BST: Ganymede emerges from Jupiter's shadow

During the early evening, Jupiter will apear to have just 3 Gallilean satellites: Io and Callisto to its right and Europa to its left. Ganymede is hiding in Jupiter's shadow but will emerge just after 22:00 BST later in the evening.

April 6th: just before dawn - the Moon occults Venus

On the 6th of the month, the Moon and Venus will lie close together low in the eastern sky before dawn. At 08:28 BST, as observed from the centre of the UK, Venus will disappear behind the disk of the very thin crescent Moon whose phase will be just 2%. This will be quite an observing challenge and will need binoculars or a small telesocpe to observe along with a good low eastern horizon. BUT BEWARE NOT TO OBSERVE CLOSE TO THE SUN! If possible stand in the shadow of a wall to the left of your position. Ideally, using an equatorial mount, locate the Moon when it rises at 06:20 BST and continue tracking as it approaches and then occults Venus. As seen from the centre of the UK, it will emerge around 20 minutes later as it briefly passes behind the Moon's northern dark limb. The occultation will not be visible from Scotland and, in the northern part of the UK, Venus will be seen to graze along the Moon's rough northern edge. Venus will take ~60 seconds to disappear and ~70 seconds to emerge. NOTE: to show the occultation graphically, I have had to remove the Sun's glare - this will be a very difficult observation.

April 8th: 45 minutes after sunset - Mercury and a thin crescent Moon

Looking west after sunset and as darkness falls, Mercury will be seen just 6 degrees to the right and slightly up from the a very thin waxing crescent Moon.

April 16th - mid evening: A waxing Moon nears Jupiter

During the evening the Moon will be seen gradually nearing Jupiter, closing in to a separation of just over 4 degrees at 22:00 UT.

April 21st all night: The Moon at apogee

On the 21st the Moon, one day from full, reaches apogee, that is at its furthest distance from the Earth. So, on the following day, it will not appear as big - or as bright - as when the full Moon is at perigee, its closest approach to the Earth. Perhaps surprisingly, its angular diameter at apogee is 12% smaller that at perigee and, should a solar eclipse occur near apogee, the Moon's full shadow may not reach the Earth giving rise to what is called an annular eclipse.

April 16th and 29th: Two Great Lunar Craters These are two good nights to observe two of the greatest craters on the Moon, Tycho and Copernicus, as the terminator is nearby. Tycho is towards the bottom of Moon in a densely cratered area called the Southern Lunar Highlands. It is a relatively young crater which is about 108 million years old. It is interesting in that it is thought to have been formed by the impact of one of the remnents of an asteroid that gave rise to the asteroid Baptistina. Another asteroid originating from the same breakup may well have caused the Chicxulub crater 65 million years ago. It has a diameter of 85 km and is nearly 5 km deep. At full Moon - seen in the image below - the rays of material that were ejected when it was formed can be see arcing across the surface. Copernicus is about 800 million years old and lies in the eastern Oceanus Procellarum beyond the end of the Apennine Mountains. It is 93 km wide and nearly 4 km deep and is a clasic "terraced" crater. Both can be seen with binoculars.

These are two good nights to observe two of the greatest craters on the Moon, Tycho and Copernicus, as the terminator is nearby. Tycho is towards the bottom of Moon in a densely cratered area called the Southern Lunar Highlands. It is a relatively young crater which is about 108 million years old. It is interesting in that it is thought to have been formed by the impact of one of the remnents of an asteroid that gave rise to the asteroid Baptistina. Another asteroid originating from the same breakup may well have caused the Chicxulub crater 65 million years ago. It has a diameter of 85 km and is nearly 5 km deep. At full Moon - seen in the image below - the rays of material that were ejected when it was formed can be see arcing across the surface. Copernicus is about 800 million years old and lies in the eastern Oceanus Procellarum beyond the end of the Apennine Mountains. It is 93 km wide and nearly 4 km deep and is a clasic "terraced" crater. Both can be seen with binoculars.

Observe the International Space Station

Use the link below to find when the space station will be visible in the next few days. In general, the space station can be seen either in the hour or so before dawn or the hour or so after sunset - this is because it is dark and yet the Sun is not too far below the horizon so that it can light up the space station. As the orbit only just gets up the the latitude of the UK it will usually be seen to the south, and is only visible for a minute or so at each sighting. Note that as it is in low-earth orbit the sighting details vary quite considerably across the UK. The NASA website linked to below gives details for several cities in the UK. (Across the world too for foreign visitors to this web page.)

Note: I observed the ISS three times recently and was amazed as to how bright it has become.

Find details of sighting possibilities from your location from: Location Index

See where the space station is now: Current Position

The Planets

- Jupiter

Jupiter reached opposition on March 8th but this is still an excellent month to observe it - high in the southern sky during the evening. It crosses the meridian at around 23:00 (UT) at the beginning of the month and around 21:00 by month's end. Its brightness falls slightly from magnitude -2.4 to -2.3 whilst its angular size drops from 44 to 41 arc seconds. Jupiter spends the month in south-eastern Leo, moving slowly westwards in retrograde motion. With a small telescope one should be easily able to see the equatorial bands in the atmosphere, sometimes the Great Red Spot (see the highlight above) and up to four of the Gallilean moons as they weave their way around it. - Saturn

Saturn rises at ~02:00 (UT) as April begins and a little earlier each night so that by month's end it rises at about 23:00 (UT). Shining at magnitude +0.3 and brightening to +0.2 during the month it lies in the southern part of Ophiuchus some 5.5 degrees up and to the left of Antares in Scorpius. Its diameter increases from 17.4 to 18.1 arc seconds as April progresses. It will be due south in the early hours of the morning at an elevation of ~19 degrees. The beautiful ring system has now opened out to ~26 degrees - virtually as open as they ever become - and measures 40 arc seconds across. It will be best observed near the meridian during the hour before dawn. If only it were higher in the ecliptic; its elevation never gets above ~19 degrees and so the atmosphere will hinder our view of this most beautiful planet. Sadly, as seen from our northern climes, on each successive apparition it will get lower in the sky, so now is the time to emigrate to the southern hemisphere!

Saturn rises at ~02:00 (UT) as April begins and a little earlier each night so that by month's end it rises at about 23:00 (UT). Shining at magnitude +0.3 and brightening to +0.2 during the month it lies in the southern part of Ophiuchus some 5.5 degrees up and to the left of Antares in Scorpius. Its diameter increases from 17.4 to 18.1 arc seconds as April progresses. It will be due south in the early hours of the morning at an elevation of ~19 degrees. The beautiful ring system has now opened out to ~26 degrees - virtually as open as they ever become - and measures 40 arc seconds across. It will be best observed near the meridian during the hour before dawn. If only it were higher in the ecliptic; its elevation never gets above ~19 degrees and so the atmosphere will hinder our view of this most beautiful planet. Sadly, as seen from our northern climes, on each successive apparition it will get lower in the sky, so now is the time to emigrate to the southern hemisphere! - Mercury

Mercury. This month, Mercury has its best apparition of the year for those of us in the northern hemisphere, shining in the west-northwest during the evening twilight. As April begins, it is low above the horizon, but shining brightly at magnitude -1.5. It reaches greatest elongation (east) on the 18th of April, so is higher in the sky, but its brightness will have dropped to a still bright magnitude 0. Then, its highest altitude at sunset will be ~19 degrees, but Mercury will still be at an elevation of ~10 degrees 45 minutes after sunset. At greatest elongation, its disk will be 7.5 arc seconds across with 38% of the disk illuminated. During the latter part of the month, it fades rapidly down to magnitude +1.5 and disappears into the Sun's glare around the 28th of the month as it moves towards inferior conjunction on the 9th of May - when we will observe a transit of Mercury - one of two major highlights for next month! - Mars

Mars. At the beginning of April, Mars rises around midnight (UT). As the month progresses it rises earlier each night so at about 10pm (UT) by month's end. It starts the month in Scorpius, moves into Ophiuchus on the 4th and, as it begins its retrograde motion westwards on April 18th, moves back towards Scorpius which it re-enters on the first of May. Its brightness increases dramatically this month, increasing from magnitude -0.6 to -1.4. At the same time its angular size increases from 12 to 16 arc seconds - the largest it has appeared for some ten years! But as it reaches opposition on the 22nd of May it will subtend over 18 arc seconds. So now is the time to start seriously observing Mars when details such as the polar caps and dark regions such as Syrtis Major should be easily visible in a small telescope on nights of good seeing. - Venus

Venus,rises less than half an hour before sunrise at the start of April and could be seen given a low eastern horizon, but it will be unobservable after the 9th or so. However, it will be worth attempring to observe it on the morning of the 6th when it is occulted by a thin crescent Moon as detailed in the highlight above.

Southern Hemisphere

Haritina Mogosanu from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during April 2016.

This campfire story is dedicated to Stuart @astronomyblog

Welcome to the month of April. My name is Haritina Mogosanu and tonight I'm your starryteller from Space Place at Carter Observatory in Aotearoa New Zealand.

I love the Milky Way. The Milky Way is the most spectacular feature of the Southern Hemisphere but to say that is such an understatement. The Milky Way is so striking here and I believe that in the absence of a polar star (which I found hard to find in the Northern Hemisphere anyway), people could even orient themselves by the Milky Way. And why not? We can easily see the Milky Way from Wellington, which according to Lonely Planet is the the coolest little capital in the world. But is still a city, which means that it does come with light pollution and from most of the cities of the world we are lucky to see just the brightest stars. Yet I have noticed when walking home at night from the Observatory, from my street I can still see the Galaxy. I call it My City of Stars. There are times when I look up and gaze straight at the center of it. This time of the year just after sunset I can see from the centre to the edge from Scorpius to Taurus, in one glorious panorama.

So in April, my beautiful City of Stars is stretching through the night sky from northwest to southeast. Allow your gaze to wander along this celestial tapestry and you will see the brightest stars. Let's start from West. Lining up onto the celestial river are:

- Very low on the horizon, Aldebaran - in Taurus, with a magnitude of 0.86. Magnitude is the logarithmic measurement of the brightness of the stars. Logarithmic means that each step of one magnitude changes the brightness by a factor of about 2.512. A magnitude 1 star is exactly a hundred times brighter than a magnitude 6 star, as the difference of five magnitude steps corresponds to 2.512 multiplied by 5, which is 100.

- Castor and Pollux - in Gemini with magnitudes of 1.93 and 1.14

- Betelgeuse - in Orion with a magnitude of 0.42

- Procyon - in the Small Dog, with a magnitude of 0.34

- And Sirius - in the Big Dog. With a mgnitude of -1.46, Sirius is among the brightest stars in the sky. By convention, the brighter the star, the smaller the number and so some stars and objects have negative magnitudes, like Sirius, or like the International Space Station which can reach up to -6 magnitude, or the full Moon, which has a magnitude of -13. The big dog constellation finally looks the right way up heading also to the western horizon too. From it, turn your gaze left.

Nearby comes Canopus -0.72, the second brightest star in the sky. Canopus is not in the white band of the Milky Way. Standing tall, Canopus is high in the sky. Canopus is a circumpolar star from Wellington, which means that it goes around in circles in 23 hours and 56 minutes, riding the celestial Ferris wheel of the Southern Skies, a giant wheel that never stops, day after day, in a sidereal time cycle, as long as the Earth is turning.

Besides Canopus, there are other stars lighting the gondolas of the big wheel but not each and every gondola has a bright star inside. If Canopus is on the top of the big wheel then just imagine that the diameter of the wheel is from Canopus to the horizon. Looking clockwise from Canopus in the 4 o'clock position on the wheel is the Lone Star, Achernar. Achernar marks the end of the grand river Eridanus, the river-asterism that flows all the way from Orion to the southern world. At 0.4 magnitude it shines bright in a region that seems devoid of other stars. Lower down, a peacock (Pavo) takes a ride on the wheel. It's main star, which carries the mundane name of Alpha Pavonis (which literally means the brightest star in Pavo), is in the 7 o'clock position on the giant turning wheel, almost as if is just hanging on the side.

Following the imaginary curve of the wheel, two very bright stars show up closer to the 10 o'clock position. Firstly, the third brightest star in the sky and our closest neighbour, Alpha Centauri, and then Beta Centauri. They point up at the Southern Cross which is even higher than them in the sky at this time of the year. And one of my favourites, the hypergiant Eta Carinae is somewhere in between Canopus and the Southern Cross. All these stars make the imaginary big wheel.

The sky looks almost devoid of stars anywhere inside my celestial Ferris wheel, with two exceptions. Let's split it in two with a diametral line that links the Alpha and Gamma Crucis, stars of the Southern Cross to lonely Achernar. On the same side as the pointers of the Southern Cross, you will find the Small Magellanic Cloud, a beautiful bright galaxy, that looks to the untrained eye (like mine) like a cirrus cloud hanging in space, 200,000 light years away. On the other side of the semicircle, another galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud compensates its loneliness by its size, from 150,000 light years away. These so called clouds that neighbour our galactic presence are visually two thirds away from the Southern cross and one third from Achernar. There is nothing else too bright within the big wheel, maybe because the wheel is inhabited by this giant spider, the Tarantula Nebula that has its nest inside the Large Magellanic Cloud. You can see its beautiful wisps through a telescope, although it is very faint. The tarantula nebula is a star-forming region, also known as 30 Doradus, and according to NASA is one of the largest star forming regions, located close to the Milky Way. About 2,400 massive stars in the center of 30 Doradus produce intense radiation and powerful winds as they blow off material into space.

While the Large Magellanic Cloud is enormous on a human scale, it is in fact less than one tenth the mass of our home galaxy. It spans just 14,000 light-years compared to about 100,000 light-years for the Milky Way and it is classified as an irregular dwarf galaxy. The ESO astronomers believe that its irregularity, combined with its prominent central bar of stars suggests to astronomers that tidal interactions with the Milky Way and fellow Local Group galaxy, the Small Magellanic Cloud, could have distorted its shape from a classic barred spiral into its modern, more chaotic form.

Crux, the Southern Cross, is no stranger to the northern hemisphere and it was entirely visible as far north as Britain in the fourth millennium BC. The Greeks could see it too but since then, the precession of the equinoxes, the wobble of Earth, its gyroscopic dance on the orbit has changed the skies a lot so that now Crux is only visible in the Northern Hemisphere from as far south as 25 degrees latitude north. Florida Keys, Puerto Rico, the islands of the Caribbean, as well as Hawaii are its northern limit of visibility. Near the Southern Cross, there is a dark patch of dust that masks the light that comes from the stars behind it and that is known as the coalsack. Inside the coalsack, the Jewel Box is one of my favourite sights that I visit over and over with the telescope.

Lower down on the path of the Milky Way the two pointers look now as if they are hanging from the Southern Cross. First comes Beta Centauri then the famous Alpha Centauri. For Maori they are also known in a different time of the year as the rope of an anchor. Here in Aotearoa, the Maori have three names for the same asterisms (groupings of stars) at different times of the year. What we know as Scorpius is now called Manaia Ki Te Rangi, the guardian of the skies. The messenger between the earthly world of mortals and the domain of the spirits, Mania also resembles to a seahorse and its symbol is used as a guardian against evil. Often you will see Maori people wearing a greenstone in Maori named pounamu Manaia as a taonga, a necklace.

Lower on the Horizon, at a magnitude of +0.95, red giant Antares shines as the brightest star in Scorpius. Right next to it, its rival, Ares by its Greek name, or Mars as we all know it better, is challenging the giant's red hue with its own red glimmer. This is how Antares got its name, as being the rival of Ares, Ant-Ares, the rival of Mars.

As the Milky Way splits the sky into two sectors, through the northeastern horizon runs the ecliptic, a lower arch, the plane of our solar system bearing the zodiacal constellations. They intersect the Milky Way right on the horizon. First to set on the western horizon, is Taurus and of it, just Aldebaran is left gleaming faintly as it passes beyond the edge of the world. The arch of the ecliptic climbs through Gemini, holder of the two bright stars Castor and Pollux, then higher up, Cancer is almost invisible to the untrained eye, a good peripheral vision training object. Leo, with the Royal Star Regulus is now host to the bright planet Jupiter, then comes Virgo with its bright star Spica, then Libra with Zubenelgenubi and Zubeneschamali the severed claws of Scorpius repurposed into a balance for Justice by the Roman Emperor Julius Caesar. Finally the arch curves down onto the western horizon where Scorpius with red Antares is carrying Red Mars. They appear around 10 PM followed by Saturn about forty minutes later. Mars will brighten steadily through the month as we catch up on it. Its distance shrinks from 118 million km away at the beginning of April to 88 million km away at the end of the month. It remains a small object in a telescope. According to our very own Alan Gilmore who received a lot fan mail about the subject, as probably did all of us, in the mid-month a telescope needs to magnify 130 times to make Mars look as big as the Moon does to the naked eye.

Saturn rises after 10:20 pm NZDT at the beginning of April; around 7:20 NZST by month's end. This also means that daylight saving starts soon and with it we will get an extra hour of sleep. Saturn is straight below Antares. If you have never seen Saturn through a telescope, the hunting season is about to open. A small telescope shows Saturn as an oval, the rings and planet blended. Larger telescopes separate the planet and rings and may show Saturn's moons looking like faint stars close to the planet. The best comment that I hear over and over from people looking through the telescope at Saturn for the first time after the ubiquitous wow is how much Saturn looks like... Saturn. Titan, one of the biggest moons in the solar system, orbits about four ring diameters from the planet. Saturn is 1400 million km away mid-month. Mercury might be seen setting in the bright twilight mid-month. It looks like a lone bright star on the northwest skyline.

This almost concludes our Night Sky South report for April 2016 but before I leave you with the peace of the night sky, I just want to quickly show you only two deep sky objects visually close to Jupiter, currently the luminary of the night sky. Jupiter is in Leo. Neighbouring Leo are Sextans and Hydra. Sextans is a "minor" equatorial constellation, a designation that made me smile. This constellation was actually invented by the famous stellar cartographer Johannes Hevelius to celebrate his sextant, a beloved instrument he used to map the sky. A copy of his famous maps adorns the ceiling of our beautiful library inside Space Place at Carter Observatory. Unknown to Hevelius, inside the celestial Sextant there is a bright galaxy NGC 3115, also known as the Spindle Galaxy. According to NASA, this field lenticular galaxy, several times bigger than the Milky Way, holds the nearest billion-solar-mass black hole to Earth whereas our supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, called Sagittarius A, has a mass only equal to about 4 million suns.

The other object that I want to show you is inside the largest of the 88 constellations in the sky, Hydra, and close to the current position of Jupiter. The remains of a dying star form a planetary nebula called NGC 3242 and nicknamed "The Ghost Of Jupiter". A planetary nebula is a slowly dying star, a star that is not too big not too small, anything say in the range of 0.8 - 8 solar masses. Planetary nebulae are beautifully coloured and it is believed that they may play a crucial role in the chemical evolution of the Milky Way, blowing out their chemical elements to the interstellar medium. Now these are the same chemical elements that make our bones, construct our skin, and basically are both the building bricks of who we are and what keeps us alive. And all these chemical elements we have on Earth have all been through the hearts of stars. I get many comments a lot of times from people telling me how small and daunted, dwarfed and insignificant they feel when they look at the stars. And that they deliberately avoid looking up. It took me many years to get my head around this but when I look up to the sky, I know for sure that I am made of stardust, and that makes me glow every day.

From Space Place at Carter Observatory here in the southern hemisphere I wish a you clear and dark skies so that we can always see the stars and remember that we are made of the same stars dust as they are.

Special Thanks go to the amazing Rhian Sheehan, Peter Detterline, Chief Astronomer of the Mars Society, Alan Gilmore from University of Canterbury and to Toa Nutone Wii Te Arei Waaka from the Society for Maori Astronomy and Traditions.

Odds and Ends

The RadioAstron project, which operates a space radio telescope antenna that can work as an interferometer with several ground-based telescopes, has used the telescope to image the quasar 3C 273. Although the quasar is over two billion light years away, the telescope was able to produce images of the centre of this quasar that are the size of 2.7 light months, which is comparable to the size of the Oort Cloud. The observations show that the quasar is much brighter than expected, which will force astronomers to revise their models for the emission from active galactic nuclei. More details are given in the press release from the NRAO.

On 14th March 2016, the first mission for the ExoMars project successfully launched two spacecraft that are now heading to Mars. The spacecraft consist of an orbiter (the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter) and a lander (Schiaparelli) that are due to arrive in October 2016. The orbiter is expected to operate until 2022 and will be used to study the gases in the Martian atmosphere, and to look for sources of methane on the Martian surface. The lander is a more short term project that will primarily demonstrate landing technologies. A timelapse video of the preparations and launch for the mission can be found here.

A group of our Jodcast ancestors have got together to produce a brand new astronomy podcast. Jen Gupta, Mark Purver, Stuart Lowe, David Ault and Megan Argo recently released the first episode of Seldom Sirius, in which they discuss Pluto's planetary identity crisis, how the number of planets in the Solar System has changed over the years because of how we classify bodies, and the latest news on ExoMars. You can keep up to date with this great new show by following them on Twitter here and on Facebook here.

Show Credits

| News: | Ian Harrison |

| Interview: | Professor Mihalis Mathioudakis and Max Potter |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and Haritina Mogosanu |

| Presenters: | George Bendo, Monique Henson, and Benjamin Shaw |

| Editors: | Adam Avison, James Bamber, George Bendo, Benjamin Shaw, and Charlie Walker |

| Segment Voice: | Kerry Hebden |

| Additional Audio: | Lizette Guzman |

| Producer: | George Bendo |

| Website: | George Bendo, Saarah Nakhuda and Stuart Lowe |

| Cover art: | Jupiter as imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope CREDIT: Space Telescope Science Institute |