Generally good. In the show this time, we talk to Dr. Tom Kitching about weak gravitational lensing, Mat rounds up the latest news, and we find out what we can see in the December night sky from Ian Morison and Haritina Mogosanu.

The News

In the news this month: one hundred years of general relativity, five fast radio bursts, and one rocky planet.

The last week of November marked the 100th anniversary of the announcement of one the most famous theories in the world: Einstein's general theory of relativity, a result of an effort almost a decade long to incorporate new relativistic physics into accelerating frames. This discovery drastically changed the perception of space and time. Unsurprisingly, Einstein's ideas were rejected by many prominent scientists at first. One of the main predictions, the fact that light does not travel in straight lines in the vicinity of massive objects, was tested, and proved almost 4 years later, by the now famous expedition led by Sir Arthur Eddington to observe the solar eclipse on May 29, 1919. A photograph taken during the eclipse revealed that some stars were in different positions to their usual place in the sky. It is worth noting that Newton's theory of gravity also predicted the bending of lightis trajectory by massive objects. The effect however would be only half as big as the one predicted by Einstein's GTR and ultimately measured by Eddington and his team. Within days of the announcement of this proof, Einstein became one of the most famous scientists in the world, which he remains until this day, and his theory has changed the way we look at the Universe. Thanks to this discovery, new areas of physics were born, such as modern cosmology. Today, the general theory of relativity still remains one of the standard tools in the arsenal of modern physics. Gravitational lensing is used to probe the distribution of ordinary and dark matter on large scales. Microlensing is a succesful method of searching for extrasolar planets, with more than 40 objects discovered to date. The work started by Karl Schwarzschild helped us to discover supermassive black holes in the centres of galaxies and study their influence on galactic dynamics and evolution. Thanks to the general theory of relativity we are now able to trace the evolution of the Universe almost right down to the very beginning. The biggest discoveres however, are yet to come. The hunt for elusive gravitational waves still continues, with many teams working around the world to provide an answer on the validity of their prediction. Important work is also being done where scientsits are trying to combine the general theory of relativity with another revolutionary development of the twentieth century: quantum physics. The general theory of relativity has remained strong for 100 years and is considered one of the most extensively tested theories of modern science, despite many claims that it fails to fully explain the evolution of the Universe. Will it hold for another 100 years? We may soon know the answer, as new tests and theories are being developed to test gravity in the most extreme enviroments, on cosmological and quantum scales.

Five new mysterious objects, known as Fast Radio Bursts have been discovered by the team of scientists conducting searches as part of the High Time Resolution Universe (HTRU) survey. This increases the number of currently known FRBs to 16, with 15 of them detected in Australia, using the 64m Parkes radio telescope and 1 at the 300m Arecibo in Puerto Rico. One of the discovered bursts shows an interesting structure, with two clearly visible peaks, separated by around 1 millisecond, making it the first such event ever discovered. Further analysis showed these two peaks were emitted at the same distance from the Earth, implying a common source. The overall characteristic of this event challenges a number of theories proposed to explain the origin of Fast Radio Bursts, which usually predict a single burst, coming from a catastrophic event, such as an evaporating black hole or a collapsing neutron star. One of the theories that can possiblity explain FRBs is that of giant and supergiant pulses. It predicts that some pulsars will emit extremely bright pulses tens to hundreds time brighter than their usual radiation. These are predicted to be extremely rare events, with repetition periods ranging from months to centuries, which explains why the efforts to reobserve some FRBs did not bring any redetections. The number of neutron starts in the observable Universe that can produce them is sufficiently large that radio astronomers should be able to observe a significant number of sources. More objects will have to be discovered to reach a definite conclusion. Significant efforts are now underway to develop new techniques for FRB detections and follow-up observations at different wavelengths, including optical, infrared and X-ray.

A new planet has been discovered in a relatively close neighbourhood to our Solar System. GJ 1132b was detected through transient and Doppler shift methods, with the former providing information about the radius of the planet and the latter about its mass. This 1.2 Earth radii and 1.6 Earth mass planet orbits its M-dwarf host star, which was found to be at a distance of 12pc (39ly) through trigonometric parallax measurements. This makes GJ 1132b the closest rocky extrasolar planet discovered to date, more that 3 times closer than the previous Earth-like record holders: 3 planets orbiting star Kepler-42, 39 parsecs away from the Sun. Despite its mass and radius, GJ 1132b is most probably nothing like Earth. The small orbital period of 1.6 days, means the planet is very close to its host star, at a distance of only 0.015AU, which is 1.5 percent of the Sun-Earth distance. At such small separation, GJ 1132b is expected to have a surface temperature of around 250 degrees Celcius, 150 degrees above the boiling point of water. This puts it closer to the harsh environment of Venus, rather than the cosy one we are used to here on Earth. Scientists are now planning further studies, including spectroscopic observations, hoping they will now be able to conduct detailed studies of the planet's atmosphere. This should provide new knowledge about the formation of planetary systems and the evolution of their atmospheres in extreme environments.

Interview with Dr. Tom Kitching

Dr Tom Kitching is a Royal Society Fellow and lecturer in the Mullard Space Science Laboratory. His research mainly focuses on weak gravitational lensing and using it to learn more about dark energy and cosmology.

Tom explains how the distortion of light from background galaxies is used to map dark matter in the Universe. Initially it was thought that this approach could be used without fully understanding the physics of galaxies. As with many things in science, it turned out to be a bit more complicated. The disagreement between results from weak gravitational lensing surveys and observations of the cosmic microwave background may suggest we need to improve our understanding of phenomena such as active galactic nuclei before we can make robust measurements using this technique.

Tom is heavily involved with weak lensing with Euclid, an optical telescope set to launch in 2020. He discusses the vast amount of data that will come from this all sky survey and how that's going to change astronomy over the next ten years.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during December 2015.

Highlights of the month

December - the first good month to view Jupiter This is the first of several great months to observe Jupiter. It now lies low in Leo and so is still reasaonably high in the ecliptic and hence, when due south, at an elevation of ~45 degrees. It is looking somewhat different than in the last few years as the north equatorial belt has become quite broad. The Great Red Spot is currently a pale shade of pink but can be easily seen as a large feature (which appears to be shrinking in size) in the South Equatorial Belt.

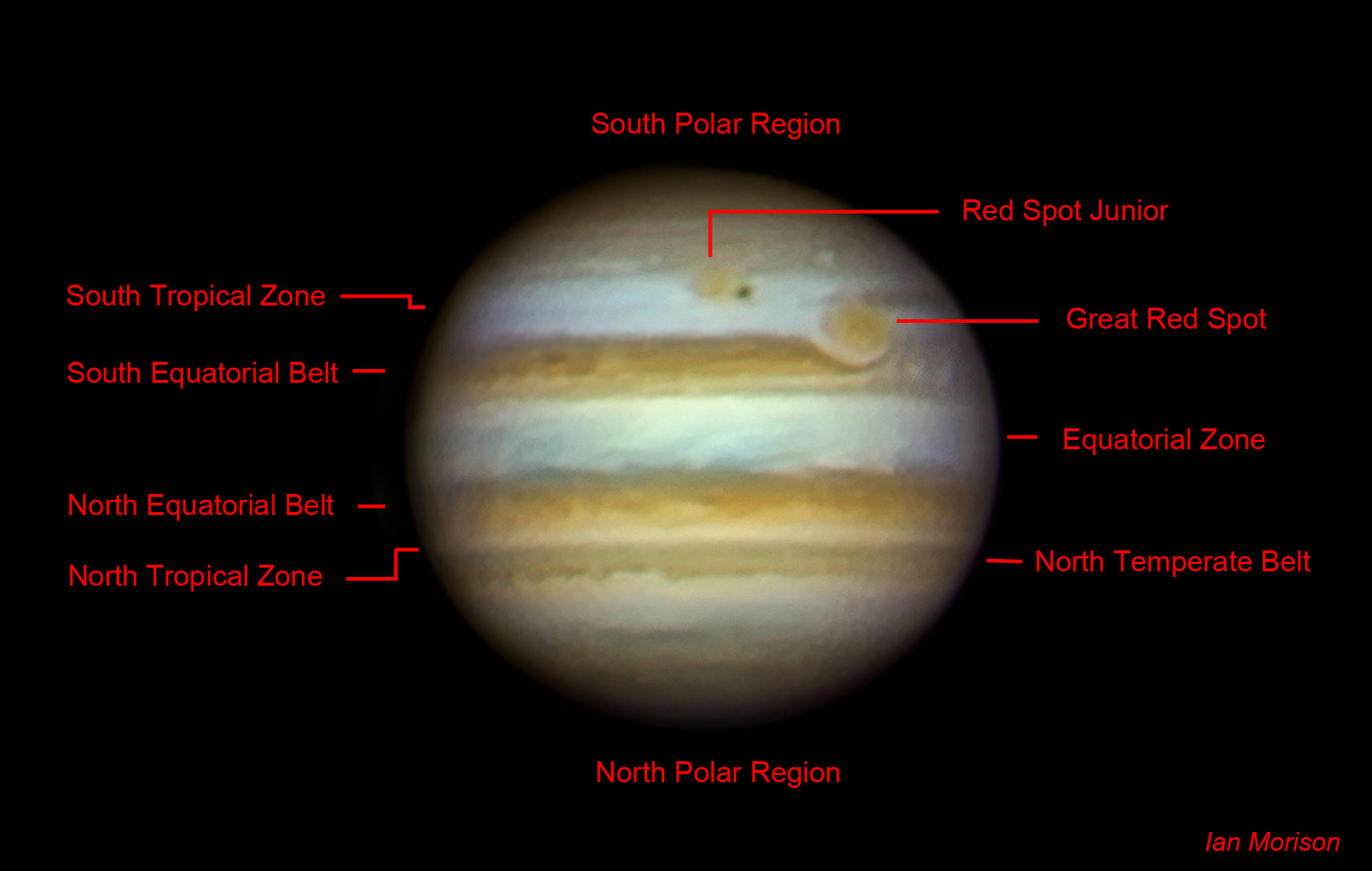

This is the first of several great months to observe Jupiter. It now lies low in Leo and so is still reasaonably high in the ecliptic and hence, when due south, at an elevation of ~45 degrees. It is looking somewhat different than in the last few years as the north equatorial belt has become quite broad. The Great Red Spot is currently a pale shade of pink but can be easily seen as a large feature (which appears to be shrinking in size) in the South Equatorial Belt. The features seen in the Jovian atmosphere have been changing quite significantly over the last few years - for a while the South Equatorial Belt vanished completely (as seen in the accompanying image by Damian Peaches) but has now returned to its normal wide state. The diagram on right shows the main Jovian features as imaged by the author at the beginning of December 2012.

The features seen in the Jovian atmosphere have been changing quite significantly over the last few years - for a while the South Equatorial Belt vanished completely (as seen in the accompanying image by Damian Peaches) but has now returned to its normal wide state. The diagram on right shows the main Jovian features as imaged by the author at the beginning of December 2012.

The image by Damian Peach was taken with a 14 inch telescope in Barbados where the seeing can be particularly good. This image won the "Astronomy Photographer of the Year" competition in 2011.

See more of Damian Peach's images: Damian Peach's Website

December - Comet Catalina heads upwards to Arcturus

As December progresses, a bright comet, 2013 US10 Catalina, will rise up into our pre-dawn skies. Initially lying close to the Virgo-Libra border, it is heading north at a rate of more than half a degree a day and, by month's end, will be easily found as it lies close to Arcturus in Bootes. By the 10th December it will stand ~20 degrees above the south-eastern horizon at 06:00 UT lying some 6 degrees above Venus. So simply find Venus in binoculars and slowly sweep up and to the left to find the comet. The best guess as to its brightness is that it will be ~5th magnitude - so not visible to the unaided eye but easily visible in binoculars.

December 4th: Jupiter and the Moon

Before dawn and looking south-east will be seen, if clear, Jupiter just over 2 degrees above the 3rd quarter Moon in Leo.

December 6th: Mars and the Moon

Before dawn and looking east will be seen, if clear, Mars just 2 degrees above the waning Moon in Leo.

December 7th and 8th: Venus and the Moon

Before dawn and looking to the east will be seen, if clear, Venus within 5 degrees (below on the 7th and above on the 8th) of a waning crescent Moon.

December 14th and 15th after midnight: the Geminid Meteor Shower

The early mornings of December 14th and 15th will give us the chance, if clear, of observing the peak of the Geminid meteor shower. Happily, this is a good a year as the waxing crescent Moon will not hinder our view. An observing location well away from towns or cities will pay dividends though. The relatively slow moving meteors arise from debris released from the asteroid 3200 Phaethon. This is unusual, as most meteor showers come from comets . The radiant - where the meteors appear to come from - is close to the bright star Castor in the constellation Gemini as shown on the chart. If it is clear it will be cold - so wrap up well, wear a woolly hat and have some hot drinks with you.

December 22nd/23rd - midnight onwards : the Ursid Meteor Shower

The night of the 22nd/23rd December is when the Ursid meteor shower is at its best - though the peak rate of ~10-15 meteors per hour is not that great. The Moon is just before full so I suspect only a very few of the brightest meteors to be seen. The radiant lies close to the star Kochab in Ursa Minor (hence their name), so look northwards at a high elevation. Occasionally, there can be a far higher rate so its worth having a look should it be clear.

December - 13th and 29th: The Alpine Valley

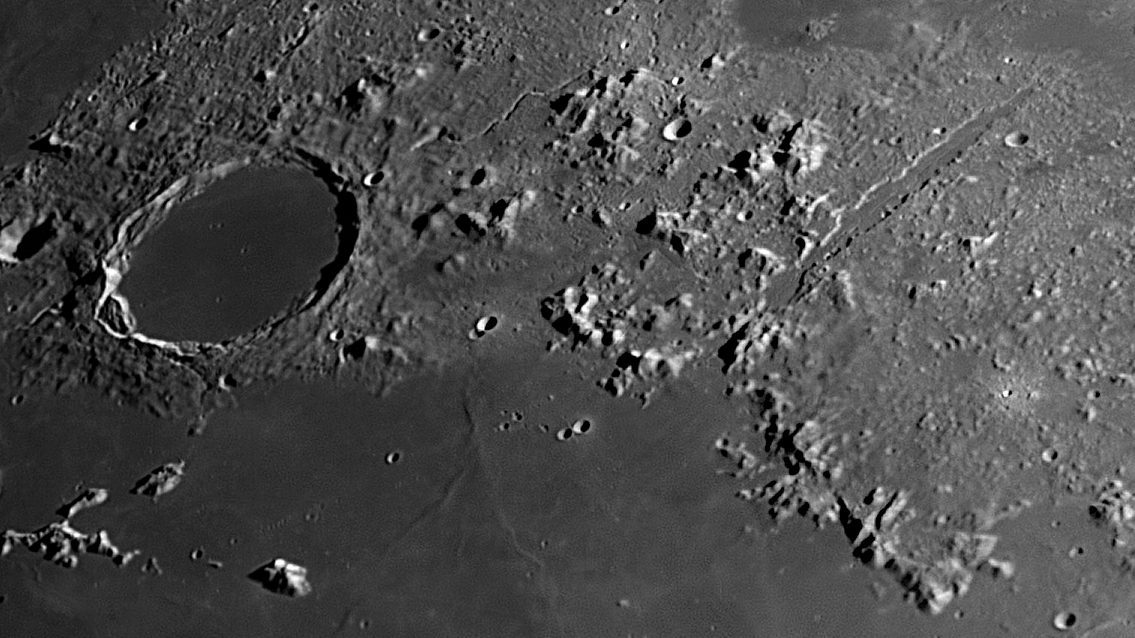

An interesting valley on the Moon: The Alpine Valley These are good nights to observe an interesting feature on the Moon if you have a small telescope. Close to the limb is the Appenine mountain chain that marks the edge of Mare Imbrium. Towards the upper end you should see the cleft across them called the Alpine valley. It is about 7 miles wide and 79 miles long. As shown in the image a thin rill runs along its length which is quite a challenge to observe. Over the next two nights following the 3rd/4th the dark crater Plato and the young crater Copernicus will come into view. This is a very interesting region of the Moon!

These are good nights to observe an interesting feature on the Moon if you have a small telescope. Close to the limb is the Appenine mountain chain that marks the edge of Mare Imbrium. Towards the upper end you should see the cleft across them called the Alpine valley. It is about 7 miles wide and 79 miles long. As shown in the image a thin rill runs along its length which is quite a challenge to observe. Over the next two nights following the 3rd/4th the dark crater Plato and the young crater Copernicus will come into view. This is a very interesting region of the Moon!

Observe the International Space Station

Use the link below to find when the space station will be visible in the next few days. In general, the space station can be seen either in the hour or so before dawn or the hour or so after sunset - this is because it is dark and yet the Sun is not too far below the horizon so that it can light up the space station. As the orbit only just gets up the the latitude of the UK it will usually be seen to the south, and is only visible for a minute or so at each sighting. Note that as it is in low-earth orbit the sighting details vary quite considerably across the UK. The NASA website linked to below gives details for several cities in the UK. (Across the world too for foreign visitors to this web page.)

Note: I observed the ISS three times recently and was amazed as to how bright it has become.

Find details of sighting possibilities from your location from: Location Index

See where the space station is now: Current Position

The Planets

- Jupiter

Jupiter shining at magnitude -2, rises at around 00:30 UT at the beginning of the month lying low down in Leo close to the boundary with Virgo into which it moves early in January. By month's end it rises about 22:30 UT and shines at magnitude -2.2 whilst, during the month, its angular size increases from 35.6 to 38.9 arc seconds It will then be due south and so highest in the sky at an elevation of 44 degrees at around 05:00 UT in the pre-dawn sky. As the Earth moves towards Jupiter, early risers should be able to easily see the equatorial bands in the atmosphere and the four Gallilean moons as they weave their way around it. - Saturn

Having passed behind the Sun on the 20th of November may be seen again around mid December rising an hour before sunrise. Sadly, it is lying in the southern part of Ophiuchus just over 6 degrees above Antares in Scorpius so its elevation when on the meridian next year will be only be 20 degrees above the horizon. It will be shining at magnitude +0.4 and, by the end of the month, be high enough in the south-east before dawn to make out the beautiful ring system which has now opened out to ~25 degrees. By month's end it rises around an hour earlier, some 2 hours before the Sun and we will see it approached by Venus as it returns towards the Sun. - Mercury

Mercury, at magnitude -5 may be seen at the end of the month low in the south-western sky as it reaches greatest elongation on the 29th of December when it lies 20 degrees from the Sun. It will be only a few degrees above the horizon at twilight and so the use of binoculars and a low horizon will be needed to spot it - but please do not try until after the Sun has set! - Mars

Mars rises in the east about 2 hours before the Sun at the start of December and about half an hour earlier as we move towards the new year. It brightens from +1.5 to +1.3 when it be nearly as bright as Spica, in Virgo, when it passes about 4 degrees up and to its left on the mornings of the 23rd and 24th of the month. It passes close to the double star Porrima at the beginning of December and, on the 12th and 13th skirts, 4th magnitude star, Theta Virginis. Mars' angular diameter will have reached just 5 arc seconds by the 10th of the month so it will be hard to spot any details on its salmon-pink surface. By month's end Mars will have reached an elevation of 28 degrees above the south-eastern horizon as dawn appears in the sky. At its closet approach in May next year its angular size of ~18 arc seconds will be greater than any time since 2005. - Venus

Venus, is now moving back towards the Sun but, by month's end still rises almost three hours before sunrise. A telescope will show that its angular size reduces from 17.5 to 14.5 arc seconds during December but at the same tine the illuminated percentage of the surface increases from ~66 percent to ~75 percent which is why the magnitude only drops from -4.2 to -4.1. Venus will lie some 5 degrees from Spica in Virgo at the start of the month, pass by the double star Alpha Librae on the 17th and 18th and will be very close to Beta Scorpii as we reach the New Year.

Southern Hemisphere

Haritina Mogosanu from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand tells us about the southern hemisphere night sky during December 2015.

Welcome to December. My name is Haritina Mogosanu and today I am your starryteller from Space Place at Carter Observatory in Aotearoa, New Zealand. The name December comes from Latin, meaning the tenth. In ancient times, it was the tenth month from the beginning of the year.

December for most of us is the time when we prepare to celebrate together, another rotation of Earth around the Sun. Of course, whilst modern life's standardisation and globalisation sees more and more people adopting this convention, it was not always like that. Different cultures celebrate the new year at different times of the year.

And it got me thinking.

Where do calendars come from? What do people see when they look at the Stars and the moon and what do these celebrations mean for us in general? And what was their connection to the land?

The Maori have a very special relationship with the Moon. They used the Moon and other celestial bodies to determine time through the year. this enabled the safety of their navigation across the oceans and the safe cultivation of their foods. The moon in new zealand is of a rare beauty as it is birthed from the ocean or it appears from behind the mountains. It appears also upside down to someone like me who is from the other side of the world.

One of our listeners told us that he is always watching the man in the Moon in the northern hemisphere (I remember watching him too) and he was curious about what we see in southern hemisphere. In New Zealand, the Maori see Rona Whakamautai - Rona, the controller of the tides. One evening, Rona travelled down to the river to collect water but the Moon disappeared behind the clouds and she cursed the Moon. Marama, the Moon, heard the curse and said, why curse such beauty when you belong to it? And lifted Rona up to become the woman of the Moon. You can see her laying down after she tripped in the dark over the ngaio tree with her water calabash behind her head. And the ngaio tree in front of her.

I was told once by a school group that there is a rabbit in the Moon. I love the kids' imagination and I always look for both the rabbit and Rona in the Moon.

Back to our stars of the southern hemisphere and the wanderers of the night sky, the generic greek name for the planets, Mercury is the only planet in the evening sky. At the beginning of the month it appears as a bright point setting in the south-west an hour after the sun. It moves slightly higher in the twilight, setting 80 minutes after the sun by the end of the month. Through a telescope it looks like a tiny gibbous moon; a moon between first quarter and full.

The brightest true stars are in the east and south. Sirius, the brightest of all the stars, is due east at dusk, often twinkling like a diamond. Left of it is the bright constellation of Orion. The line of three stars makes Orion's belt in the classical constellation. To southern hemisphere skywatchers they make the bottom of 'The Pot'. The faint line of stars above and right of the three is the Pot's handle. At its centre is the Orion Nebula, a glowing gas cloud nicely seen through binoculars. Rigel, directly above the line of three stars, is a hot blue-giant star. Orange Betelgeuse, below the line of three, is a cooler red-giant star.

Left of Orion is a triangular group making the upside down V of the Hyades. Orange Aldebaran is the brightest star in the V shape. Aldebaran is one of the four royal stars. These royal stars were regarded as the guardians of the sky in approximately 3000 BCE during the time of the Ancient Persians in the area of modern day Iran. The Persians believed that the sky was divided into four districts with each district being guarded by one of the four Royal Stars. The royal stars held both good and evil power and the Persians asked them for guidance in scientific calculations of the sky, such as the calendar and lunar/solar cycles, and for predictions about the future. Other names for the hyades were the little she camels, and were forming the second nakshatra, rohini in hindu astrology.

Still further left is the Pleiades cluster, impressive through binoculars. It is 440 light years away. Pliny talked about them: In cauda Tauri septem quas appelavere Vergilias - at the tail of the bull Vergilias calls seven. The Pleiades seem to be among the first stars mentioned in astronomical literature, appearing in chinese annals of 2357 BC.

Canopus, the second brightest star, is high in the southeast. Low in the south are the Pointers, Beta and Alpha Centauri, and Crux of the Southern Cross. As we mentioned in the November Jodcast, end of November - beginning of December is the time when the grand canoe of tama rereti is the sky. the bright southern Milky Way makes the waters in which the canoe is anchored, with Crux being the canoe's anchor hanging off the side. In this picture the Scorpion's tail is the canoe's prow and the Clouds of Magellan are the sails.

The Milky Way is wrapped around the horizon. The broadest part is in Sagittarius, low in the west at dusk. It narrows toward the Crux in the south and becomes faint in the east below Orion. The Milky Way is our edgewise view of the galaxy, the pancake of billions of stars of which the sun is just one. The thick hub of the galaxy, 30 000 light years away, is in Sagittarius, now low in the west. The nearby outer edge is the faint part of the Milky Way below Orion. A scan along the Milky Way with binoculars will show many clusters of stars and a few glowing gas clouds.

The Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, high in the southern sky, are two small galaxies about 160 000 and 200 000 light years away, respectively. They are easily seen by eye on a dark moonless night. The larger cloud is about 1/20th the mass of the Milky Way galaxy, the smaller cloud 1/30th.

Formalhaut or Hastorang as it was known to the ancient Persians is also one of the four royal stars, it's finding now its true home in the southern hemisphere. I remember watching it in awe from the northern hemisphere, as it was showing the secret passage to the south to those who knew how to read it.

Very low in the north is the Andromeda Galaxy seen with binoculars in a dark sky as a spindle of light. It is a bit bigger than our Milky Way galaxy and nearly three million light years away.

Jupiter, Mars and Venus are all visible in the morning sky. Saturn joins them at the end of the month. At the beginning of December Jupiter rises around 2:30 a.m.; reducing to 12:30 a.m. by the 31st. It is a bright golden-coloured 'star' shining with a steady light. Venus is up around 4 a.m., a brilliant object bright enough to cast shadows in dark locations. Mars is between the two bright planets, looking like a medium-bright reddish star. Jupiter and Mars rise steadily earlier while Venus stays put in the dawn. In the second half of the month Mars is near, then passing below, the bluish-white star Spica, the brightest star in Virgo. At the end of the month Saturn emerges from the dawn twilight below and right of Venus, at the bottom end of the diagonal line of planets. The crescent moon will be close to Venus on the morning of December 8th.

A small telescope shows Jupiter's disk with its four big moons like faint stars lined up on each side. They change sides from night to night as they orbit the planet. Jupiter is 794 million km away mid-month.

The Geminid meteor shower peaks on the morning of the 15th. The meteors appear to come from the constellation of Gemini, low in the northeast at midnight, moving to the north by dawn. The meteors are clumps of dust from a comet. Friction with the air heats them up and makes the air around them glow.

Special Thanks go to Peter Detterline, Chief Astronomer of the Mars Society, Alan Gilmore from University of Canterbury and to Toa Nutone Wii Te Arei Waaka from the Society for Maori Astronomy and Traditions.

This concludes our jodcast for December 2015 at Space Place at Carter Observatory. As the Maori say, E whiti ana nga whetu o te Rangi (the stars are shining in the sky) Ko takoto ake nei ko Papatuanuku (whilst Mother Earth lays beneath)

May you enjoy the end of another happy rotation around the sun! Kia Kaha and clear skies from the Space Place at Carter Observatory in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Odds and Ends

At the end of November NASA installed the first of eighteen hexagonal mirrors on to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). This 1.3m mirror made of ultra-lightweight beryllium will be part of the final 6.5m primary mirror of JWST, which is due for launch in 2018. Amazingly the mirror is so large it has to be folded up for launching into space. It will then fold out once JWST gets into its observing position in space. A successor to Hubble but working at longer infrared wavelengths JWST hopes to shed (IR) light on everything from early stars 13.5billions years ago at the dawn of the Universe to the atmospheres of exoplanets here in the Milky Way.

A piece of a SpaceX rocket was found in the sea of Scilly a few days ago, to everybody's great surprise. It's unclear whether it was from the failed Falcon 9 launch in 2015, or a piece of the first stage of CRS 4, which successfully launched in 2014. Read about it here.

The Moon's orbit is tilted slightly, by 5 degrees, contrary to predictions that it should in the Earth's equatorial plane. Simulations suggest that this may be due to some gravitational interaction with large bodies during the Moon's early years. This may also explain the abundance of precious metals, such as gold, in the Earth's crust: precious metals would have sunk to the centre of the Earth during formation, but passing bodies may have deposited material onto the Earth's surface during the interaction.

Show Credits

| News: | Mateusz Malenta |

| Interview: | Dr. Tom Kitching, Monique Henson and Max Potter |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and Haritina Mogosanu |

| Presenters: | Hannah Stacey, Adam Avison and Fiona Healy |

| Editors: | Benjamin Shaw, James Bamber, Nialh Mccallum, Haritina Mogosanu and Charlie Walker |

| Segment Voice: | Kerry Hebden |

| Website: | Saarah Nakhuda, Charlie Walker and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Charlie Walker |

| Cover art: | A portrait of Albert Einstein, refracted by an almost-perfectly spherical gyroscope used to test his theory of general relativity. CREDIT: Wikimedia Commons |