In this show, we talk to Dr Alan Duffy about simulating the earliest galaxies, Indy rounds up the latest news and we find out what we can see in the October night sky from Ian Morison and Claire Bretherton.

The News

In the news this month: complex molecules, and clear skies.

One of the big questions that often comes up when astronomy and astrophysics are mentioned is: 'Is there life out there?' While the search for extraterrestrial life has sparked the imaginations of countless people from astronomers to science-fiction authors, and even spawned a serious scientific organisation (SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence), most attempts focus on detecting some sort of signal indicative of cogent life forms in another star system, or even another galaxy. The only such possible detection we know of occurred on the 15th of August, 1977, in the context of a SETI project: the 'Wow!' signal, as it is known, was detected by the Big Ear radio telescope at Ohio State University. A strong radio signal lasting 72 seconds (the length of the scanning window) was picked up, with a peak signal-to noise ratio of about 30. Many signs pointed to this being extraterrestrial in origin, but the signal was never detected again.

However, a different kind of radio detection has recently raised the possibility of there being life in our Galaxy - just maybe not as we know it. Astronomers from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany and Cornell University in the USA have announced the detection of an unusual, complex carbon-based molecule - in a giant interstellar gas cloud. Located some 27,000 light years away, the gas-rich, star-forming region Sagittarius B2 was found to emit spectral lines corresponding to complex, carbon-based molecules. The team used ALMA (the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) to study the various emission lines present in the extremely large and dense gas cloud, which was previously found to contain other complex molecules. While 180 different molecules have already been detected in the interstellar medium as a whole, the largest of these have all been organic, with what is known as a 'straight-chain' carbon backbone, which is to say that the carbon atoms in the molecule all link up in a straight line and do not 'branch out'. For the first time, these astronomers have detected branched carbon molecules - specifically a branched alkyl known as iso-propyl cyanide, chemical formula C3H7CN. According to the astrochemical models used by the scientists, the observed molecules are produced on the surface of icy dust grains by the addition of radicals to simple molecules via various reactions.

The reason scientists are hailing this as a landmark detection is due to the fact that the branched structure seen here is a characteristic property of amino acids, which are complex molecules that form the building blocks of protein. Such molecules have previously been encountered in meteorites that have landed on Earth, but it was uncertain whether the right conditions were present in interstellar space for the formation of amino acids and other branched carbon molecules, which are crucial for the development of life. Now, the possibility is very much alive - no pun intended - that such molecules may be produced very early in the star formation process. The scientists involved in the study are hopeful that amino acids and other such branched carbon molecules will be detected in the near future, as the sensitivity and resolution of radio telescopes continue to improve. Perhaps, one day, we will have evidence of the chemical, rather than electromagnetic, variety, that life elsewhere in the Cosmos truly does exist.

In other news: space weather of a different kind.

Astronomers have detected the smallest exoplanet containing water in its atmosphere yet. The planet, roughly the size of Neptune, is known by the designation HAT-P-11b, and was studied by using the Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes to measure the variation of its parent star's light as it transited across. The spectrum of the light during the transits was closely studied, and, although the occurence of water vapour in exoplanet atmospheres is fairly common, the researchers were suprised to find that the planet's atmosphere was also cloud-free - a first for this type of exoplanet. Studying the absorption spectra of hydrogen and oxygen in the atmospehre of the planet, they saw that the intensity of the observed signal meant that the skies were clear, as far as Hubble could see. This is in contrast to previous spectral observations of other exoplanet atmospheres, which have revealed very little information due to a thick, cloudy atmosphere always being present. In the case of HAT-P-11b, the location of the water in the atmosphere points towards a planetary model of a gassy planet with a rocky or icy core. Future observations of other exoplanets hope to reveal more cases of 'good weather' in the future!

Interview with Dr Alan Duffy

Dr Alan Duffy works at Swinburne University in Melbourne, using cosmological simulations to study galaxies and the large-scale structure of the Universe. He tells us about his PhD at the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, in which he was looking at gravitational simulations of dark matter, and he explains how this can model the behaviour of the Universe even though we don't really know what dark matter is. He then moves on to his current work on hydrodynamical simulations, in which 'normal' matter is added to the mix, creating gas flows and supernovae for a more realistic picture. He discusses how the results of these simulations will inform the aims of the Square Kilometre Array radio telescope, and explains that they suggest that a population of small galaxies was partly responsible for reionising the hydrogen in the Universe with the first stars. Alan also talks about his extensive astronomy outreach work in Australia.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during October 2014.

The constellations of Cygnus, Lyra and Aquila are almost overhead in the evening, with their bright stars Deneb, Vega and Altair forming the Summer Triangle. The Square of Pegasus is to the lower left of Cygnus. If you move from its top-left to the next bright star, fork a little to another star and go the same distance again, before turning sharply right to find another star, then carrying on a little further brings you to the fuzzy glow of the Andromeda Galaxy. If you go back to the sharp right turn and carry on the same distance again, binoculars may pick up the Triangulum Galaxy as well. Andromeda can also be found by moving along the Milky Way from Deneb to the W-shape of the Cassiopeia constellation and following the V of the three highest stars like an arrow. Moving a bit further along the Milky Way, and dropping down between two stars towards Perseus, you can locate the beautiful Double Cluster.

The Planets

- Jupiter, at magnitude -1.9, rises around 02:30 BST (British Summer Time, 1 hour ahead of Universal Time, UT) at the beginning of the month, 7° to the lower left of M44, the Beehive Cluster. It passes from Cancer into Leo on the 14th. It brightens to magnitude -2 and rises well over an hour earlier by the end of the month, which seems earlier still for observers whose clocks go back at the end of October. Jupiter's disc grows from 34 to 36" during October as the Earth approaches it, and a small telescope can reveal its equatorial bands and four largest moons. The Great Red Spot is also visible at certain times, and appears to be shrinking slightly.

- Saturn is past its best apparition of the year, but can still be seen 7° above the south-western horizon an hour after sunset at the beginning of the month. It lies in Libra and shines at magnitude +0.6.

- Mercury is well placed in the pre-dawn sky at the end of the month. On the 22nd, it has a magnitude of +2 and rises at 07:00 BST, reaching 8° above the horizon by dawn and sitting 11° from the Sun in our sky. Be careful not to look for it once the Sun has risen, as your eyes could be damaged. Mercury reaches western elongation (its furthest point west from the Sun in the sky) on the 1st of November, when its disc measures 7" across and is 50% illuminated.

- Mars starts October in the often-forgotten zodiacal constellation of Ophiuchus, moving into Sagittarius on the 21st. Its magnitude dims from +0.8 to +0.9 over the month, while its angular size drops from 6 to 5.6". It sets about 2.5 hours after the Sun for the whole month, so you may be able to spot it, but it is hard to make out surface details.

- Venus rises half an hour before the Sun at the start of October, shining at magnitude -3.9, but is soon lost in the morning glare and moves behind the Sun (superior conjunction) on the 25th, not to reappear for around a month.

Highlights

- The planet Uranus reaches reaches opposition (opposite the Sun in the sky) on the 7th, so it is at its closest point to the Earth and lies due south around midnight UT. At magnitude +5.9, binoculars can locate it in the southern part of Pisces, to the east of the Circlet asterism that forms the head of one of the Fish, and is 3° south of the line joining the fourth-magnitude stars Epsilon and Delta Piscium. Its highest elevation is about 45°, attained around midnight. A telescope of some 4.5 inches in aperture should show the planet's pale turquoise disc, 3.6" across. An 8-inch telescope may reveal cloud formations, which are currently more prominent than usual.

- Jupiter is 10° to the east of a waning crescent Moon in Leo an hour before sunrise on the 17th.

- The Orionid meteor shower may produce up to 10 visible meteors per hour between 01:00 and 05:00 BST from the 17th to the 23rd. The radiant of the shower, which originates from Comet Halley, is to the upper left of Orion's red giant star, Betelgeuse.

- Mercury lies 7.5° below a thin crescent Moon half an hour before sunrise on the 22nd, but you will need a low eastern horizon to see it.

- The waxing crescent Moon occults (passes in front of) Saturn from around 16:59 to 18:03 on the 25th for UK observers, with exact times varying from place to place and in other countries. It is hard to spot, coming before sunset and dropping from 12 to 6° in height during the occultation. The Moon, just 3% illuminated, covers Saturn with its dark limb and uncovers it from its bright side.

- Mars passes just 6° below a thin crescent Moon an hour after sunset on the 27th.

Southern Hemisphere

Claire Bretherton from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during October 2014.

The winter constellation of Scorpius (Te Matau a Māui to Māori) is dropping towards the western horizon, and sets by midnight NZDT (New Zealand Daylight Time, 13 hours ahead of Universal Time). Meanwhile, Orion is rising in the east, along with the other summer constellations of Taurus and Canis Major. Mercury can still be spotted low in the west-south-west during the first week of October, while Saturn is below Scorpius and sets around 22:00 NZDT. Mars continues to hang halfway up the western sky after dark. Comet Siding Spring C/2013 A1 passes within 138,000 kilometres of Mars on the 19th-20th, and may be visible in binoculars from Earth. Approaching Mars from above as seen from the southern hemisphere, it is 4.4° away on the 15th, then passes beneath it and moves to the lower left of the globular cluster NGC 6401 on the 20th. Uranus is in Pisces, to the north-east, and Neptune is in Aquarius, higher in the north, but neither can be seen with the naked eye. Jupiter is the brightest planet currently in the sky, and rises in the north-east around 04:30 NZDT at the beginning of the month, its largest moons visible in binoculars.

Pegasus, the Winged Horse, straddles the northern horizon in the evening. Identified by a large square of stars, its brightest member is the orange supergiant Epsilon Pegasi, or Enif, named after the Arabic word for the Horse's nose. Nearby is the M15, which may be the densest globular cluster in our Galaxy. With a magnitude of +6.2, it appears as a fuzzy glow in binoculars, while a telescope can pick out chains of stars radiating out from the core. M15 also contains the planetary nebula Pease 1, the first such object to be found within a globular cluster. At magnitude +15.5, a telescope of 30 centimetres in aperture is required to see it. Alpheratz, the star at the bottom of the Great Square of Pegasus, is a great place from which to star-hop to the Andromeda Galaxy, which appears near the northern horizon in southern hemisphere skies only at this time of year. To find it, move along the uppermost of two chains of stars that extend east from Alpheratz, pass Delta Andromedae, turn sharp right at Mirach, carry on to Mu Andromedae and then go the same distance again to the galaxy. At 2.5 million light-years' distance, it is the most distant object normally visible to the naked eye from Earth.

Highlights

- The full Moon provides a total lunar eclipse over much of the Earth on the night of the 8th-9th, beginning some two hours after moonrise for observers in New Zealand. As the Moon moves through the Earth's shadow, a penumbral phase (beginning around 21:15 NZDT) is seen when the Earth blocks only part of the Sun's light, an umbral phase (around 22:14) follows when the centre of the Earth begins to cast its shadow, and totality (23:25 to 00:24) occurs when the Earth puts the Moon into full darkness. Even then, refraction of sunlight by the Earth's atmosphere gives the Moon a red tint.

- The zodiacal light can be spotted this month, making a triangular glow in the western sky after sunset. Caused by the reflection of sunlight by dust in the plane of our Solar System, this weak glow requires a dark, clear sky in order to be seen. It appears in the zodiacal constellations because it lies around the ecliptic, and the steep angle of the ecliptic at this time of year pushes it higher into the sky. The time around new Moon, on the 24th, is best for observing it.

Odds and Ends

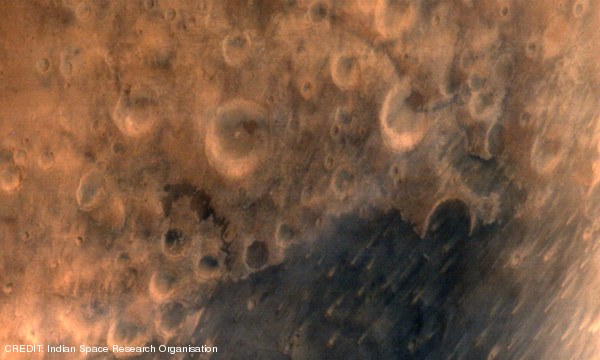

On the November 2013 Extra episode of the Jodcast, we mentioned the launch of the Mars Orbiter Mission (also nicknamed Mangalyaan) by the Indian Space Research Organisation. On 24 September, Mangalyaan entered into orbit around Mars. This was India's first interplanetary space mission ever, and it is also remarkable given the relatively low budget (4.5 billion rupees, equivalent to 74 million US dollars or 45 million British pounds) and given that both the United States and the former Soviet Union failed in their first Mars space missions. The spacecraft only weighs 15 kilogrammes and contains a relatively limited amount of instrumentation, but it will play a key role in searching the Martian atmosphere for methane, which could be an indicator of biological activity on the planet. More information is available from the BBC article announcing the success of the spacecraft entering orbit as well as an additional BBC analysis of the mission.

NASA's Cassini spacecraft has spotted another mysterious wave-like feature on the surface of one of Titan's seas. This follows the earlier discovery of a similar feature on Saturn's largest moon in July 2013, which had since disappeared. Its reappearance is interesting as it implies that the feature observed in July was neither a transient phenomenon nor an instrumental flaw. Scientists at NASA will continue to monitor Titan's seas for waves.

The evidence for gravitational waves in the early Universe is looking a little shakier following new analysis of the cosmic microwave background (CMB). Earlier this year, the BICEP2 mission released data from the CMB that appeared to show the polarised patterns expected to have been caused by gravitational waves that were stretched by cosmic inflation in the first moments after the Big Bang. However, the signature could also be caused by foreground emission such as spinning dust in the Milky Way, and BICEP2 could not gather the information necessary to subtract that signal. The most recent findings of the Planck mission show that such a foreground has contaminated the BICEP2 data, but it is not yet clear whether this can fully explain the observations or whether the signature of inflation may yet remain after it is subtracted.

Show Credits

| News: | Indy Leclercq |

| Interview: | Dr Alan Duffy and Mark Purver |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and Claire Bretherton |

| Presenters: | George Bendo, Fiona Healy and Mark Purver |

| Editors: | Adam Avison, Claire Bretherton, Sally Cooper, Indy Leclercq and Mark Purver |

| Segment Voice: | Tess Jaffe |

| Website: | Mark Purver and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Mark Purver |

| Cover art: | The first image of Mars taken by the Mars Orbiter Mission. CREDIT: Indian Space Research Organisation |