In this show, we talk to Dr Richard Shaw about detecting Baryon Acoustic Oscillations, Indy rounds up the latest news and we find out what we can see in the September night sky from Ian Morison and Claire Bretherton.

The News

In the news this month: early monster stars, and a new address for the Milky Way.

As any astronomer will confidently tell you, we are all made of stars. That is to say, our constituent atoms - carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, calcium and the rest - were all created by nuclear interactions occurring within stars, and for elements heavier than iron, in exploding stars (known as supernovae). It is therefore possible to deduce a lot of information about a star by measuring the relative quantities of elements inside it, and the older a star is, the more heavy elements it will contain. But if we go back far enough, it stands to reason that the first stars after the Big Bang could only contain the elements that were formed at that point in time - Hydrogen, Helium and a very small amount of Lithium. Simulations of stellar evolution have predicted that this first generation of stars would be gigantic, with some being more than 100 times bigger than the Sun! The thing about stars, though, is that the bigger they are, the shorter their lifetime. So these behemoths would have only lasted a few million years before exploding in supernovae, releasing the heavier elements they had formed into the universe and 'seeding' the next batch of stars. At least, that's how the theory goes. But no evidence for the existence of such massive stars has previously been found.

A team of astronomers at the National Astronomical Observatory in Tokyo, led by Wako Aoki, think they're on to something, though. Practicing what could be called 'stellar archaeology', they have found clues to the existence of the first generation of massive stars by studying a very old star that could be a direct descendant of the old giants. Small, slow-burning stars can have an extermely long lifespan, with the oldest having been around for around 13 billion years - they are almost as old as the universe itself. Previous studies have used these stars to figure out the chemical composition of the early universe, and trace its evolution. The proportions of elements in the stars studied (known as 'abundances' in astronomy), however, had so far not provided evidence in favour of the existence of truly gigantic stars. The star analysed by Aoki and his team proved to be somewhat different. Originally found by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, SDSS J0018-0939 was analysed using a spectrograph located on the island of Mauna Kea, Hawaii. The results showed that the star had a very distinct chemical profile, containing a much higher abundance of iron relative to lighter elements such as carbon or magnesium. This implies that the matter the star was formed from was the result of a specific kind of supernova known as a pair-instability supernova.

Pair-instability supernovae only occur in very massive stars, where the temperature in the core gets so high that the photons inside the star (which supply the radiation pressure required to stop the star collapsing inwards due to gravity) spontaneously convert into electron-positron pairs. This removes the radiation pressure, and triggers a runaway collapse followed by a violent explosion of the core. The iron present in the core would then be flung out, rather than sucked back into the core to form a black hole, which is what happens in lower-energy supernovae. The unique iron abundances in J0018-0939 suggest that a huge star, ending its life in a pair-instability supernova, was responsible for its formation. Given the advanced age of the observed star, its parent star would effectively meet the criteria for being one of those first, gigantic stars.

There are some caveats to the theory, though. This is only one star amongst many, many others, and a statistical sample would have to be built up to be able to state with any accuracy that this is the explanation for the observed abundances. Furthermore, Aoki acknowledges that some aspects of the element profile are still unexplained. There is still plenty of work to be done, and models need to be improved before clear conclusions can be reached. Future telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope, will be able to provide more stars for study, and may even be able to witness the explosive deaths of the first stars directly, in light coming form the most distant galaxies - which will be irrefutable proof of the existence of the first-generation giants.

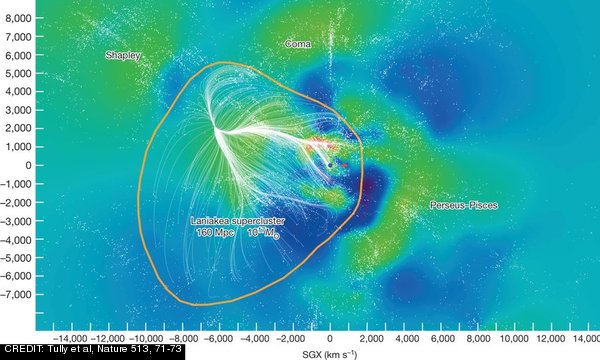

In other news, astronomers have mapped the supercluster of galaxies that contains our own Milky Way, and have defined a new way to separate one supercluster from another. Using a database compiling galaxy velocities, they constructed a three-dimensional field of galaxy flow and density, effectively trying to understand the large scale motion that gravity imprints on galaxies. This 'movement map' takes into account all matter with gravitational pull, meaning it accounts for the effects of dark matter. The map shows flow lines which trace the general movement of galaxies, and defines boundaries between clusters as points on the map where the lines go in different directions. The researchers found that using this definition, the Virgo supercluster that is home to our Milky Way becomes simply a subset of the larger supercluster, dubbed Laniakea - Hawaiian for 'immeasurable heaven'. 100 times the size of Virgo, it is 520 million light years across and contains the mass of 100 million billion suns. However, other research on superclusters is ongoing, and this find is unlikely to be the final word on the matter.

Interview with Dr Richard Shaw

Dr Richard Shaw works at the University of Toronto, and is participating in a project called the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME). He explains how the custom-made CHIME telescope will detect radio emission from cold hydrogen in distant galaxies, and how this will be used to make measurements of the expansion of the Universe that complement those from the cosmic microwave background and from the observed distribution of galaxies in optical light. He also discusses how cosmological redshift allows us to distinguish the radiation emitted by hydrogen at different times in our Universe's history, and how such radiation can be separated from the the foreground emission of our own Milky Way that is a million times stronger.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during September 2014.

The Summer Triangle consisting of the stars Vega, Deneb and Altair is still high in the sky. The asterism of the Northern Cross, near to Deneb, contains the multicoloured double star Albireo. Another double star, Epsilon Lyrae, can be found using binoculars near to Vega, and a telescope reveals that it is itself a pair of doubles. The constellation of Delphinus is below the Summer Triangle, with Aquarius and Capricornus further down still. The Square of Pegasus rises in the east as the evening progresses, and following the arc of the head of Pegasus leads to the globular cluster M15, while the top-left corner of the Square (or, alternatively, the topmost stars of Cassiopeia) can be used to locate the Andromeda Galaxy. Perseus is in the north-east, below Cassiopeia, and binoculars show that the Double Cluster, a pair of open star clusters, lies between them.

The Planets

- Jupiter, shining at magnitude -1.8, begins September 2.5° from M44, the Beehive Cluster. It is moving through Cancer towards Leo, rising 2.5 hours before the Sun at the start of the month and 4.5 hours before it at the end. Jupiter's disc grows from 32.1 to 33.6" in angular diameter over the month, allowing the equatorial bands and Galilean moons to be seen.

- Saturn, at magnitude +0.6 and 16" across, can be seen low in the south-west after sunset, lying in Libra. It is 20° above the horizon an hour after sunset at the beginning of the month, dropping to 10° by the end, and will soon disappear behind the Sun. Saturn's rings are inclined at 23° to the line of sight, giving a good view, and the planet's largest moon, Titan, should be visible through a telescope.

- Mercury is not readily visible this month, due to its low elevation. It may be spotted around the 20th of the month using binoculars - after the Sun has set - some 5-10° above the horizon and around 25° to the left of where the Sun has gone down, shining at magnitude 0. Mercury is just 0.5° below the first-magnitude star Spica, in Virgo, on the 20th.

- Mars moves quickly eastwards, progressing from Libra into Scorpius and ending the month close to the red star Antares. During September, it dims from +0.6 to +0.8 in magnitude and shrinks from 6.8 to 6.1" across. It is low in the south-west at sunset, with the Earth's atmosphere making it difficult to see surface details. Mars lies halfway between Saturn and Antares on the 12th, and 0.5° above Delta Scorpii on the 17th.

- Venus rises in the east-north-east an hour before sunrise at the beginning of September, and only half an hour before it at the end. It can be seen in Leo early in the month, positioned to the lower left of Jupiter and shining at magnitude -3.9.

Highlights

- Neptune can be spotted using binoculars or a small telescope this month, sitting in Aquarius with a magnitude of +7.9. It reaches an elevation of 27° when due south, shortly after midnight BST (British Summer Time, 1 hour ahead of Universal Time). A telescope of 8" in aperture should be able to pick out its largest moon, Triton.

- Venus is just 1° from the bright star Regulus in Leo half an hour before sunrise on the 5th.

- The planets Mars and Saturn are close to the star Antares in the south-western sky an hour after sunset on the 5th, but a low horizon is required to see it.

- Jupiter is 6° from a thin crescent Moon before dawn on the 20th.

- Saturn, Mars and a crescent Moon appear together in the sky after sunset on the 27th and 28th.

- The Alpine Valley is a nice feature of the Moon to observe on the 2nd and 14th, when it is close to the limb. It lies in the Apennine mountain chain that marks the edge of the Mare Imbrium, and a thin rill can be seen running along it using a medium-sized telescope. The craters Plato and Copernicus appear well around the same dates.

Southern Hemisphere

Claire Bretherton from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during September 2014.

The spring equinox arrives this month, so the nights are rapidly getting shorter. The bright stars Vega and Canopus mark the northern and southern horizons at dusk, with the band of the Milky Way passing overhead between them. Vega is part of the Winter Triangle, along with Deneb and Altair. Between Vega and Altair is the lovely double star Albireo, marking the beak of Cygnus the Swan. The winter constellations of Scorpius and Sagittarius are sliding towards the western horizon night by night, with Orion rising opposite them as they set. Between them are Capricornus, Aquarius and Pisces.

Capricornus, often depicted as a cross between a goat and a fish, appears as an elongated triangle of stars, while a smaller triangle marks its head and horns. Its brightest star is Delta Capricorni or Deneb Algedi, and it changes significantly in brightness because it is an eclipsing binary, in which two stars partially block one another from our view as they orbit. The system is now known to contain four stars. Alpha Capricorni, or Algedi, is a double star whose members can just be distinguished with the naked eye, but the two stars are not in a binary system as they are at very different distances from us. The watery constellations in this part of the sky are associated with autumn and winter rains in the northern hemisphere, and to the south-east of Capricornus is Piscis Austrinus, the Southern Fish. The bright star Fomalhaut, marking its mouth, has a planetary companion that was directly imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope.

The constellation of Aquarius the Water-carrier, lying between Fomalhaut and Altair, contains a number of beautiful deep-sky objects. M2 is a globular cluster near to the third-magnitude star Beta Aquarii. Visible in binoculars, a telescope of 20 centimetres in aperture shows up individual stars. The Helix Nebula, or NGC 7293, is a planetary nebula positioned south-west of Delta Aquarii that appears as a hazy circle in binoculars. A telescope reveals the darker area in the centre, while a long-exposure photograph brings out the nebula's colours. Pisces, Cetus and Delphinus are more water-themed constellations in this area of the sky.

The Planets

- Mars and Saturn are about halfway up the north-western sky in the evening at the beginning of the month, and are joined by a crescent Moon on the 1st. Saturn is sliding towards the western horizon, but Mars moves east on its faster orbit and, at the end of the month, passes close to its namesake, the red star Antares - the 'Rival of Mars'.

- Mercury makes its best appearance of the year this month, joining Mars and Saturn in the western sky after dark. Its fast, close orbit means it never gets far from the Sun in our sky, but it reaches eastern elongation - its greatest separation to the east - on the 22nd. Mercury passes close to the star Spica, in Virgo, on the 20th.

- Jupiter shines brightly in the north-east in the morning, rising around 1.5 hours before the Sun by the middle of September. Binoculars or a telescope show its four largest moons.

Highlights

- The last of three 'supermoons' of 2014 occurs on the 9th, when the Moon is almost full at its closest approach to the Earth and looks bigger and brighter than usual.

Odds and Ends

Two of ESA's Galileo global navigation system hit a snag in August, when two of its satellites were placed into the wrong orbits. The European constellation, which will work alongside the American GPS and Russian GLONASS systems, should provide superior positioning accuracy of just one metre to ground-based receivers once all thirty satellites are in orbit in 2017. The fifth and sixth, however, are now in lower orbits than intended, and it is not clear whether they can be used within Galileo. The 70 kilogrammes of fuel aboard each satellite, intended to keep their orbits from gradually falling over the course of many years, may or may not be enough to reposition them.

New measurements of the distance to the Pleiades have reignited an argument between scientists on both sides of the Atlantic. American scientists, using the VLBA telescope array, have found a different distance to that measured by European counterparts using the Hipparcos space telescope. The issue is hoped to be resolved when the Gaia telescope finishes taking data.

Show Credits

| News: | Indy Leclercq |

| Interview: | Dr Richard Shaw and Mark Purver |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and Claire Bretherton |

| Presenters: | Indy Leclercq and Mark Purver |

| Editors: | Indy Leclercq, Claire Bretherton, and Mark Purver |

| Segment Voice: | Tess Jaffe |

| Website: | Indy Leclercq and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Indy Leclercq |

| Cover art: | A slice of the Laniakea supercluster in the supergalactic equatorial plane. CREDIT: Tully et al, Nature 513, 71-73 |