In the show this time, we conduct a linguistic interchange with Prof. Ian Shipsey regarding the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, Indy issues a bulletin acknowledging the latest triumph of computational analysis in astronomy and Ian Morison and John Field describe what the human eye can detect during the nocturnal hours of the lunar period known as April. Meanwhile, our new, more efficient presenters bring us superior odds and ends.

The News

In the news this month: BICEP2 flexes its muscles.

The astronomical community has been abuzz recently with the news that the BICEP2 experiment has detected a signal in the cosmic microwave background (or CMB) that provides evidence for the cosmological theory of inflation. But what does it all mean, and why are the astronomers so excited?

It's worth beginning at the beginning - of the Universe, that is. According to currently accepted cosmological theory, which describes the evolution of our Universe on a large scale, the Universe began at a single point and expanded outwards. This is the famous 'Big Bang'. Ever since this theory was posited, astronomers have been trying to 'wind back the clock' and figure out what was happening at moments closer and closer to the singularity at the beginning of the Universe. The discovery of the CMB was a big piece of evidence in favour of the Big Bang, as it is essentially a snapshot of the moment of recombination, when the Universe was just 300,000 years old. Before this time, the Universe was filled with a mixture of very energetic particles (essentially protons and electrons) and photons. The protons and electrons formed a plasma which trapped the photons, stopping them from propagating through the Universe. However, as the Universe kept expanding, it cooled, and the protons and electrons lost enough energy to combine with each other into hydrogen atoms. At this point the photons were 'freed', and began travelling through the Universe. This first light is in fact what we see today as the CMB; in the intervening 13-odd billion years the universe has expanded and stretched out the frequency of the light so that we measure the CMB as microwave radiation.

There were some problems with the Big Bang model, though. Firstly, the so-called 'horizon problem': in a Universe that looks the same in all directions, how did two regions too far away to be in causal contact with each other end up having the same properties? When we look at two different regions of the CMB that are separated by more than 13.7 billion light years (which is the age of the Universe), they have the same temperature to within a ten-thousandth of a degree. The problem is that, during the entire lifetime of the Universe, light emitted from one region can't yet have reached the other one, and it would be extremely unlikely for the two regions to independently end up at the same temperature (thermal equilibrium in cosmological terms)! Another issue is the 'flatness problem': we observe the curvature of the Universe (which can be understood as a measure of the geometrical properties of spacetime) to be very close to perfectly flat. However, for this to occur, the energy density of the Universe (matter, radiation, dark matter and so on) has to be fine-tuned to a very specific value, which is extremely unlikely. The third problem usually brought up is the magnetic monopole problem, which suggests that, in the early, very hot, Universe, exotic particles such as magnetic monopoles could be produced that would subsist today at densities high enough that we should be able to detect them - however, this isn't the case.

Cosomologist Alan Guth was working on trying to explain this problem when he hit upon the theory of inflation. The basic principle of inflation theory is that, at some very early time in the Universe, space underwent an exponential expansion, growing at a rate much faster than the speed of light. This is thought to have occurred from 10^-36 seconds to 10^-32 seconds after the Big Bang. After more work by Guth and other cosmologists including Andrei Linde, it was realised that inflation could account for all the discrepancies listed above. Take the the horizon problem: if all parts of the Universe were causally connected before inflation, they would be in thermal equilibrium. Inflation would then stretch the space at a rate faster than the speed of light, thus explaining how regions that we percieve to be causally unconnected to each other can look the same. It also solves the flatness problem: inflation makes it possible to have a flat Universe with far less constraint on the initial energy density of the Universe. Finally, it can also explain the monopole problem: if inflation occurred after the exotic particles were produced, then the exponential expansion of space would greatly reduce the density of these and make them extremely rare, which is why we haven't found them today.

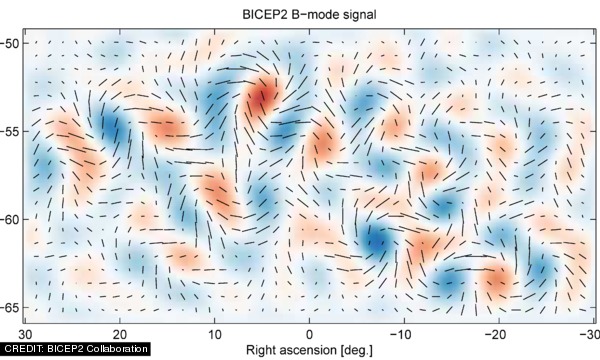

The first models of inflation were proposed in the early 1980s, and many, many different models have emerged since - it turns out that there are plenty of ways of generating this exponential expansion. However, experimental verification was proving extremely elusive: inflation was a good idea, but it doesn't leave many traces behind. One possible way of detecting it is to look for the imprint left on the CMB by the gravitational waves caused by inflation. Indeed, as the Universe blew up in size, this generated so-called 'primordial gravitational waves', with a distinct signature. These waves propagated through space, and would have been strong enough at the time of recombination to polarise the radiation of the CMB. The main polarised component of the CMB is the 'E-mode' polarisation, caused by the variations in temperature in the Universe at the moment of recombination; these are known as scalar perturbations. The gravitational waves create what are known as 'tensor perturbations', and these imprint a certain type of polarisation, known as 'B-mode' polarisation, in the CMB. The great difficulty, though, was that B-modes are extremely faint, and very difficult to detect.

This is where BICEP2 comes in. Located at the South Pole, and the successor to the BICEP experiment, the BICEP2 telescope observed a small patch of the sky, known for having weak microwave emission, for two years. On the 17th of March, the team announced that they had detected B-modes in the CMB. More precisely, they announced that they had a value for the tensor-to-scalar ratio (r) of the polarisation, which compares the relative amounts of E-mode and B-mode polarisation. They found a result of r=0.2, while stating that r was greater than zero to a very high degree of certainty. This is an extremely exciting result, as it is possible proof not only of inflation, but also of gravitational waves, which have never been detected in such a direct manner. However, caution is necessary: confirmation of the result is needed from other experiments measuring the CMB before any conclusions about inflation or gravitational waves can truly be reached. The Planck Collaboration, mapping the CMB from space with their eponymous satellite, is expected to release polarisation data later this year; and new data from BICEP2's successor, the Keck Array, will enable scientists to say more. Nevertheless, if the detection is confirmed, it is the first step in an exciting new era for cosmology and understanding the history of our Universe.

Interview with Prof. Ian Shipsey

Professor Ian Shipsey is a particle physicist at Oxford University, and is involved in the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) project. This 8-metre optical telescope is due to begin an unprecedented survey of the sky in 2022, imaging all that it can see and repeating these observations twice a week for 10 years. Prof. Shipsey describes the scope of the measurements that will be done, finding billions of galaxies in the Universe, stars in the Milky Way and small bodies in our Solar System. He talks about the benefits that will emerge, from a better understanding of dark energy through the mapping of galaxies in space and time to a more complete knowledge of potentially threatening asteroids through the cataloguing of 90% of the near-Earth objects that are over 140 metres in diameter. He explains how the vast quantity of data generated by the LSST will be processed using both computers and citizen science, and describes how astronomers will be alerted to transient phenomena detected by the telescope.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during April 2014.

The constellation of Gemini and the planet Jupiter are setting in the west as the Sun goes down. Leo, with its bright star Regulus, is in the south, and to the left of Regulus are the galaxies M95, M96, M66 and M65, which are visible in binoculars or a small telescope. To the left of Leo, more such objects can be found in a region between Coma Berenices and Virgo known as the Realm of the Galaxies, which looks towards the Virgo Cluster. The bright star Arcturus is to the south-east, in Bo”tes, with the circlet of stars called Corona Borealis to its left. The bright star Vega rises in the north-east later in the evening, in Lyra, followed by Cygnus and the Milky Way. Ursa Major is almost overhead, containing the famous asterism of the Plough, or Big Dipper. If you look diagonally up the trapezium-shaped part of the Plough from bottom-left to top-right, and then carry on for the same distance again, you reach the galaxies of M82 and M81. M82, nicknamed the Cigar Galaxy, is a starburst galaxy where many new stars and supernovae can be seen. The middle star of the Plough's handle is actually a double, with two components called Mizar and Alcor, or the Horse and Rider. A telescope shows that Mizar is itself a double star, and another, reddish star appears in the same field of view.

The Planets

- Jupiter is a little past the best of its current apparition, but is still high in the sky just after nightfall, shining at magnitude -2.2 at the beginning of the month. Its angular size reduces from 38 to 35" during April, but you can still see the Galilean moons and, when the seeing is good, the Great Red Spot at certain times.

- Saturn is coming to the best of its apparition, rising at 22:30 UT (Universal Time) at the start of the month and 20:30 UT at its end. It has a magnitude of about +0.1 and moves retrograde through Libra, its angular diameter increasing from 18.2 to 18.6" during April. Its rings are now at 22° to the line of sight and span 40" across, allowing a small telescope to pick out the Cassini Division in good seeing conditions. Unfortunately, Saturn does not currently rise very high in the sky for northern hemisphere observers.

- Mars is in Virgo and reaches opposition (opposite the Sun in the sky) on the 8th, so it is visible throughout the night and reaches its highest point in the sky at about 02:00 BST (British Summer Time, 1 hour ahead of Universal Time) at the start of the month and 23:00 BST at the end. Mars is at its brightest, around magnitude -1.5, in the second week of April, and comes closest to Earth in its current orbit on the 14th, when it is just over 15" in angular diameter. The surface is about 91% illuminated, and features can be seen with a small telescope. The planet moves retrograde and approaches the bright star Porrima.

- Mercury is just visible above the eastern horizon before sunrise at the beginning of the month, but is then lost as it passes superior conjunction (behind the Sun in the sky) on the 26th.

- Venus rises before morning twilight as April begins and can be spotted at magnitude -4.4, but its is below 10° elevation at sunrise. Its brightness drops to -4.2 as it gets closer to the Sun in the sky during the month, and it shrinks from 22 to 17" across even as its illuminated fraction goes up from 54 to 66%.

Highlights

- Jupiter is still prominent in the sky this month. Its surface features have changed over the last few years, with the South Equatorial Belt disappearing and reappearing again.

- The large asteroids Vesta, at magnitude +5.8, and Ceres, at magnitude +7, reach opposition on the 13th and 15th respectively. They are only 2.5° apart all month, allowing them to be seen together in binoculars, and lie up and left of the bright star Spica in Virgo. The best time to spot them is towards the beginning or end of April, when the Moon is not in the way.

- Mars is less than 5° from the nearly-full Moon after sunset on the 14th, in the south-east, with Spica only 4° away on the other side of the Moon.

- Venus is just 6¥ from a thin, waning crescent Moon before dawn on the 26th, rising in the east.

- The great lunar craters of Tycho and Copernicus can be observed, as always, around the time of full Moon, which occurs on the 15th of this month.

- If you have a large radio polarimetric bolometer array to hand, why not try to observe the effect of gravitiational waves on the cosmic microwave background at any time and in any part of the sky? All you have to do is clear away the foregrounds that make up the rest of the Universe first.

Southern Hemisphere

John Field from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during April 2014.

The daylight hours continue to shorten as the southern hemisphere progresses through early autumn. Three bright planets can be seen in the early evening sky: Jupiter in the north-west, in Gemini, Mars in the north-east, shining with an orange-red hue near to the star Spica in Virgo, and Saturn, which follows Mars in Libra. Mars makes the closest approach to Earth in its current orbit this month, while Saturn's rings and its largest moon, the orange-coloured Titan, are well placed for viewing with a telescope. Mars and Saturn are high in the sky by midnight and above Mars is a kite-shaped quartet of stars in the constellation of Corvus the Crow. Delta Corvi is a wide double star, but there are few other easily-observed objects in the vicinity. Nearby is Hydra the Water Snake, a long path of stars with a distinct group of five stars forming its head.

The winter constellation of Scorpius rises in the east in the evening. Its brightest star, at magnitude +1, is the red supergiant Antares, known as the Rival of Mars because of its colour. It is called Rehua by Māori in Aoteroa (New Zealand), and marks the eye of Māui's fishing hook. This hook is called Te Matau a Māui, for which the back and stinger of the Scorpion's body become the curve and tip of the hook. According to Māori mythology, the great hero Māui used this hook to pull the North Island of New Zealand from the ocean, for which that part of the country is named Te Ika-a-Māui - the Fish of Māui. The tip of the hook crosses a wide and bright part of the Milky Way, and in this part of the sky we are looking towards the Galactic centre, some 30,000 light-years away. The Southern Cross of Crux and its pointer stars are found by running up the Milky Way, as are the Diamond and False Crosses. Crux is called Te Punga in Māori star lore. The hero Tamarereti sailed across the heavens in his Waka, or canoe, placing the stars into the sky, and Te Punga was his boat's Anchor. You can find south halfway between Crux and the bright star Achernar, in Eridanus, by following the line from the top to the base of the Cross. Two-thirds of the way along this line are the Magellanic Clouds, dwarf satellite galaxies of the Milky Way.

Highlights

- Venus and Mercury are both visible low in the east before dawn in the first week of April.

- New Zealand and eastern Australia are treated to a total lunar eclipse as the Moon rises at sunset on the 15th, while central and western Australia see a partial phase of the eclipse.

- Australia witnesses a partial solar eclipse in the late afternoon of the 29th.

Odds and Ends

Show Credits

| News: | Indy Leclercq |

| Interview: | Prof. Ian Shipsey and Mark Purver |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and John Field |

| Presenters: | CPU 001 and CPU 002 |

| Editors: | Adam Avison, Libby Jones, Indy Leclercq, Mark Purver and Christina Smith |

| Segment Voice: | Iain McDonald |

| Website: | Mark Purver and Stuart Lowe |

| Cover art: | The first evidence of primordial gravitational waves in the cosmic microwave background (CMB), detected by the BICEP2 telescope. The lines show the magnitude and direction of the linearly polarised component of the CMB; the red and blue patches indicate regions where the direction is twisted clockwise and anticlockwise, which is the giveaway signature of the effect of gravitational waves in the early Universe. CREDIT: BICEP2 Collaboration |