Inhabitable? In the show this time, Dr. Manda Banerji talks to us about dusty quasars, Prof. Ian Browne talks to us about the BINGO telescope in this month's JodBite, your astronomical questions are answered by Dr. Joe Zuntz in Ask an Astronomer and Stuart rounds up the March news, one episode later than usual.

The News

In the news this month we peer deeply into the world of an ancient x-ray mirror.

It is believed that at the heart of most, if not all, galaxies there lies a supermassive black hole. In the present epoch of the universe most supermassive black holes reside invisibly in the centre of their host galaxy, this however was not always the case. Earlier in the universe galactic cores were far more turbulent than they were today. Galactic mergers or extreme star formation led to large amounts of gas and dust being available to potentially fall into the supermassive black holes. Hot disks and powerful jets would form from the infalling gas, which illuminated the cores of earlier galaxies. These sorts of galaxies are known as active galactic nuclei, and the brightest of these are known as quasars.

We are able to see that the lives of supermassive black holes have evolved and changed alongside their host galaxies throughout the age of the universe, this tells us that the properties of a galaxy's supermassive black hole are intrinsically linked to the events of a galaxy's past. Black holes are in some ways relatively simple objects. They have only two quantities which describe them, their mass and their angular momentum or spin. The mass can tell us about how much material a black hole has accreted, and generally larger black holes will reside in larger galaxies. However the angular momentum of a black hole can tell us about how the black hole gained that mass. Was it chaotic, the matter falling in bit by bit sporadically over the millennia? This is the case for most nearby quasars in the present universe. Or was the supermassive black hole fed continuously, surrounded always by an ample supply of gas and dust to feed on? As is expected to be the case for younger quasars earlier in the universe. Clearly then, understanding the angular momentum of a black hole is vitally important for us to know how the cores of galaxies have changed from being material rich to material poor. One critical question which astronomers studying quasars want to know is, exactly when did this change occur and how fast did it occur.

In order to measure the angular momentum of a supermassive black hole you need to be able to isolate the x-ray spectrum being emitted from the immensely hot gas in the immediate vicinity of the black hole. These are areas comparable in size to our solar system but in objects that are millions, or even billions of light years away. This means our telescopes need to be able to take extremely high resolution observations to distinguish the disc from the surrounding galaxy. Not only that though, the x-ray signals that astronomers are looking for are not the powerful ones that are emitted directly from the hot gas around the black hole but from x-rays which are reflected off the hot gas which substantially dimmer in intensity. This means that with our current generation of x-ray observatories we can only take accurate measurements of the reflected x-ray spectrums for some nearby quasars. Which is unfortunate since ideally we will need to have many measurements of different quasars at all different ages of the universe, going back as early as possible, if we want to make any definite conclusions as to how the evolutions of galaxies are linked to the supermassive black holes at their cores.

What is it that is different about reflected x-rays though? Why do we need to measure them instead of the far brighter directly emitted x-rays? The critical difference is that reflected x-rays are encoded with the emission lines of material within the hot disc. However, due to the proximity of the hot disc to the black hole, these emission lines are smeared out by the immense whipping up of space-time caused by the spinning black holes powerful rotating gravitational field. By measuring the shape of the smeared emission lines it possible use Einstein’s equations of general relativity to predict the angular momentum of the black hole.

So what can we do then to measure these reflected x-rays in more distant and earlier quasars? One solution is to simply wait for bigger and better x-ray observatories, which ultimately will be necessary, but in the mean time there is another way in which we can gain some insight into the nature of these more distant quasars, thanks once again to Einstein's general relativity. A team of astronomers published this month their analysis of the reflected x-rays from a quasar 2 billion years younger than any other previously measured. They were able to do this because the quasar in question was being gravitationally lensed by a nearby large galaxy that lay in front of it. The gravitational lense acted to magnify and multiply the intensity of the x-rays from the distant quasar, effectively making it as bright as far nearer quasars. What the astronomers found was that this quasar seemed to exhibit the characteristics of a supermassive black hole that was continuously feeding on the gas within the core of its host galaxy. This is contrary to supermassive black holes in the present universe which feed only sporadically on the occasional misfortunate gas cloud which strays too close. Although this is only a peak into to this earlier period in this history of the universe, it does seem to indicate that it is within that time that galaxies began to undergo significant changes, becoming calmer, less violent places.

JodBite with Prof. Ian Browne

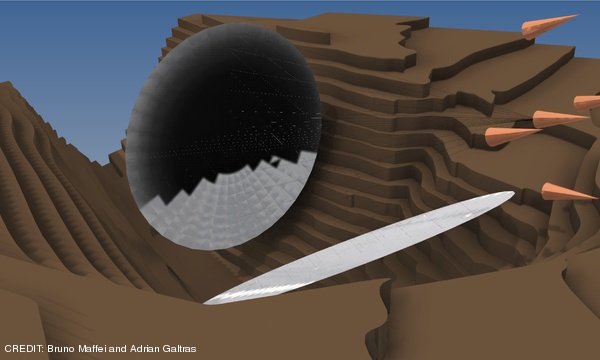

Professor Ian Browne is an emeritus professor of radio astronomy at the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, and is currently involved in the design of BINGO, a proposed radio telescope with a long focal length and a consequent wide field of view. The aim of this specialised instrument is to map baryon acoustic oscillations (BAOs) using the radio emission of cold hydrogen at a wavelength of 21cm. These oscillations originate from acoustic ripples in the hot, dense plasma of the early Universe, and today appear as an imprint in the separations of galaxies in space. As Prof. Browne explains, BINGO will probe BAOs at a range of relatively recent epochs in the Universe, with the radiation from each epoch stretched to a certain wavelength by the expansion of the Universe. This will complement other measurements of BAOs, helping to determine whether the dark energy that seems to be accelerating the expansion is changing over time.

Interview with Dr. Manda Banerji

Dr. Manda Banerji is a post-doctoral fellow at UCL, and her research is primarily focused on so-called 'dusty quasars'. She starts off by explaining what a quasar is, and why dusty quasars are particularly interesting. She discusses the methods of observing the quasars - using the UKIRT and the VISTA telescopes - and how the study of these, especially at high redshifts, can shed a lot of light on the early stages of galaxy formation. However, dusty quasars are very rare objects and they are very challenging to observe. Nevertheless, Dr. Banerji is very optimistic about the future technologies that will enable even better observations.

Ask an Astronomer

Dr. Joe Zuntz answers your astronomical questions:

- Patrick Bosque wrote in to say:"In your January extra Ask an Astronomer one question concerned the Big Bang and black holes. I have had a possibly similar question for a while: in the initial period after the Big Bang, wasn't the mass density in all space so high that the gravitational force should have caused everthing to collapse into a black hole? i.e. if all matter/energy (except vacuum energy) that is present today was also present when space was much much smaller right after the Big Bang, how is it that any was able to escape what must have been enormous mutual gravitational attraction to form the seperate galaxies etc that make up the universe today?"

- The next question, from Colin Stenning, is: "Is it possible that there is a connection between Dark Energy and some as yet undiscovered properties of the Higgs Field, that might point the way towards some sort of grand unified theory in the future?"

- Finally, Leonard Pendlebury asks: "The Andromeda Galaxy - which is bigger than the Milky Way - is heading our way. How long will Andromeda take to reach us, and what will happen to the black hole at the centre of our galaxy?"

Odds and Ends

Timothy Peake, the British ESA astronaut who was selected in 2009 will be carrying out his first mission to the International Space Station (ISS) in November 2015. This will be the first time that a British astronaut will set foot on the ISS, and this mission needs a name! ESA has opened this up as a competition to the general public. The competition is open until early April and the winner will be given a mission patch signed by Tim Peake.

A group of scientists have may have discovered the first liquid waves seen outside the Earth, using Cassini observations of Saturn's largest moon, Titan. They analysed specular reflection (reflected sunlight) from Titan's northern hydrocarbon lakes in several colour filters, finding that some areas were brighter than would be expected from a completely flat surface. The readings were consistent with waves just 2 centimetres high and caused by winds of 0.75 metres per second, but they could also have originated from rippled 'mudflats'. Previous research has always found a surprising smoothness to the lakes, perhaps caused by the viscosity of the fluid, which includes substances such as methane at temperatures of some -180 degrees centigrade. As Saturn moves towards the northern summer solstice of its 30-year orbit around the Sun, astronomers are hoping the winds will pick up and generate larger waves, with forecasts of hydrocarbon rain.

Show Credits

| News: | Stuart Harper |

| JodBite: | Prof. Ian Browne and Mark Purver |

| Interview: | Dr. Manda Banerji and Indy Leclercq |

| Ask An Astronomer: | Dr. Joe Zuntz and Indy Leclercq |

| Presenters: | Fiona Healy, Mark Purver and Christina Smith |

| Editors: | Indy Leclercq, George Bendo, Stuart Harper and Mark Purver |

| Segment Voice: | Iain McDonald |

| Website: | Indy Leclercq and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Indy Leclercq |

| Cover art: | An artists impression of the planned BINGO radio telescope, which is the subject of this month's JodBite with Ian Browne CREDIT: Bruno Maffei and Adrian Galtras |