In the show this time, we talk to Prof Clive Tadhunter about AGN and their trigger mechanisms, Stuart rounds up the latest news and we find out what we can see in the November night sky from Ian Morison and John Field.

The News

This month in the news, how a supernova becomes a hypernova.

At the dawn of the cosmos, the first stars ignited from the quiescent clouds of hydrogen that filled the universe. These first stars would be almost entirely made from hydrogen gas and, compared to the stars of today, were enormous, easily reaching hundreds of times the size of our own Sun in terms of mass. What allowed these monster sized stars to form was the lack of metallic elements in the very beginning of the universe. The difference between metal rich and metal poor star forming clouds are that the metal rich clouds are able to more rapidly cool the gas which they contain. This means that when new stars form from the gravitational collapse of the gas within a nebula the point at which the nuclear fusion of the new star begins, also the point at which new star stops growing, is earlier for metal rich nebulae than in metal poor nebulae. This results in the present universe where the largest star that can form is up to hundred times more massive than the Sun.

What happens then to stars that are more than hundred times more massive than the Sun? Finding out by direct observations of such stars is almost impossible since it was about six billion years ago that the universe became too metal rich for them to form, so any which are potentially visible will be within extremely distant galaxies. However we have observed the unique supernova explosions which occur upon theirs deaths known as pair-instability supernovae which are over hundred time brighter than other kinds of supernovae, sometimes known also as hypernovae. Models of stars can tell us more about the processes that lead up to these hypernovae. First the star begins as almost entirely hydrogen, over time this hydrogen is converted into helium via the fusion processes that light up the star. Once all the hydrogen is exhausted the star has a moment where it no longer has enough energy pushing out from its core to hold up its enormous mass, so it begins to collapse towards the centre. The act of collapsing heats up the now helium filled core of the star until the helium can begin to fuse and stop the collapse of the star. Eventually the helium is also exhausted and it is at this point that the star rapidly begins travelling along the path to going supernova. First the core stops fusion again, the star’s outer layers fall inwards to the centre and again the core heats up. However this time the momentum of the infalling outer layers is not stopped when the, now oxygen rich, core begins to fuse because some of the light emitted during fusion is so energetic it is spontaneously turning into matter, one electron and one positron, a matter and anti-matter pair. This means that there is nothing pushing on the outer layers to stop them falling inwards. This causes a sudden burst of rapid oxygen fusion to occur which is so violent it blows the entire star apart, leaving nothing behind. We have observed a number of these types of supernovae, the first back as early as the nineties at a range of different times after the Big Bang starting about 8 billion years ago.

Back in 2007 astronomers spotted a supernova explosion several days after it had reached its peak brightness but they could still estimate that it was much brighter than any normal supernova. Quickly it was proposed that it was a pair-instability supernova but there was a problem, it seemed to occur only a billion years ago, essentially the present day universe, a time when it should be impossible for the sort of super massive metal poor stars that cause these supernovae to form. Since then at least two more nearby hypernovae have been seen, perhaps one supermassive low metal star may have formed in the recent universe but multiple examples definately should not be possible. Either our understanding of how metals are enriching the star forming regions in the universe is wrong or our understanding of what is causing these hypernovae is wrong.

Last month a team of researchers published in Nature an alternative mechanism for hypernovae which would allow them to occur without the star needing to be large enough for a pair instability to form in the stars core. They propose that the nearby hypernovae can be explained by the collapse of metal rich stars in a normal core collapse supernova event. How it works is that instead of a typical neutron star forming upon the death of a metal rich star, instead the neutron star is imbued with an extremely powerful magnetic field, this sort of neutron star is called a magnetar. The magnetars magnetic field then acts to energise the entire supernova pushing its peak brightness up to the same levels as a pair instability supernova. When the researchers compared their models for a magnetar based hypernova and the pair instability models with the data observed in 2007 and the other nearby hypernovae they found the magnetar model agreed better. The two key observational points being that the peak brightness of the observations rose and fell much faster than a pair instability supernova could. Although this means that the hypernovae nearby were not from stars like those that formed in the first round of star formation at cosmic dawn of the universe, we at least still can be sure that our current understanding of stellar evolution is correct. Of course there are still several hypernovae that occurred at greater distances, earlier in the universe, that we have observed therefore we still have examples of those very first stars to study.

Interview with Clive Tadhunter

Prof. Clive Tadhunter from The University of Sheffield talks to us about Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) and how they are triggered.He starts off by explaining what, exactly, AGN are - and then goes on to explain how we think they come into existence. Current theories believe that galaxy mergers are what trigger the inflow of gas towards a central black hole necessary for the generation of huge amounts of energy and light via accretion, although Prof. Tadhunter explains that the picture isn't as straightforward as that.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during November 2013.

The Summer Triangle is visible, as usual. It is in the west after sunset, while Pegasus makes its way over to the south-west during the evening. The globular cluster M15 is close to the star Enif, at the front of the head of the upside-down Winged Horse. Alpheratz, one of the upper stars in the Square of Pegasus, can be used as a starting point to locate M31 and M33, the Andromeda and Triangulum Galaxies. Taurus rises in the south-east in the evening, containing the Hyades and Pleiades Clusters. Cassiopeia is high overhead, and you can follow the Milky Way down from there to Auriga, with its bright yellow star Capella, and then Gemini, with the stars Castor and Pollux forming the heads of the Twins.

The Planets

- Jupiter rises around 21:00 UT (Universal Time) at the beginning of the month, and reaches 60° elevation when due south at about 05:00. It has a magnitude of -2.4 and can be found near to the star Wasat in Gemini, which has a magnitude of +3.5. It begins moving westward (retrograde) relative to the stars on the 7th. Jupiter rises by 19:00 UT at the end of November, crossing the south at 03:00, and reaches a magnitude of -2.6 and an angular diameter of 45". A small telescope shows the Galilean moons and the Great Red Spot in the South Equatorial Belt, as well as shadow transits on the nights of the 5th-6th and 12th-13th.

- Saturn passes behind the Sun (conjunction) on the 6th, but reappears in the pre-dawn sky around the 22nd, when it is close to Mercury and just above Comet ISON.

- Mars begins its current apparition in earnest, rising around 01:30 UT at the start of the month. During November, it brightens from +1.5 to +1.2 in magnitude and grows from 4.9 to 5.6" in angular size, allowing surface features like the polar caps to be discerned through a telescope. It moves from Leo into Virgo on the 25th.

- Mercury passes between the Earth and the Sun (inferior conjunction) on the 1st. It returns to the pre-dawn sky around the 9th, shining at magnitude +0.8. It brightens thereafter, remaining visible until early December.

- Venus is at its furthest point east from the Sun in the sky (eastern elongation) on the 1st, but its low elevation makes it more difficult to observe, as it reaches a maximum of 9° at the beginning of the month and 14° at the end.

Highlights

- Venus lies beneath a thin crescent Moon about 45 minutes after sunset on the 6th.

- Shadow transits of Jupiter's moons Io and Europa can be seen on the nights of the 5th-6th and 12th-13th, as the satellites cast eclipse shadows over the Jovian surface. Io itself can also be seen distinctly from Jupiter during the event on the 5th-6th.

- It is a good time to observe the Andromeda Galaxy this month, as it is high in the sky around 20:00-21:00 UT.

- The Leonid meteor shower peaks on the night of the 16th-17th, although the full Moon will obscure many of the shooting stars. The meteors appear to radiate from the constellation of Leo, which rises in the east around midnight.

- It is a good time to observe Neptune this month, and the planet can be found in Aquarius using binoculars or a telescope.

- Comet ISON should become visible in binoculars or a small telescope in the hour before dawn from around the 16th onwards. It is predicted to reach magnitude +3 to +4, and may be visible to the unaided eye if it does so. Moving quickly as it nears the Sun, the comet advances through Leo, Virgo and Libra before entering Scorpius. It passes by the bright star Spica in Virgo on the 17th and 18th, and approaches Mercury and Saturn in the sky around the 21st, but will be getting lost in the Sun's glare around this time. It will reappear in December as it moves away from the Sun, but its nucleus, of some 3 kilometres in diameter, may break up in the heat at perihelion, making its brightness afterwards difficult to forecast.

- Mercury and Saturn are in close conjunction before dawn on the 26th, with a chance of spotting Comet ISON below them.

Southern Hemisphere

John Field from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during November 2013.

After sunset, the winter constellations are seen sliding towards the western horizon as the summer stars rise in the east. Scorpius is one of those setting, and its tail marks one of four pillars in Māori star lore. Ranginui, the Sky Father, rests on these pillars, and the other three mark the rising points of Te Rā (the Sun) at the solstices and equinoctes, as seen from New Zealand: Takurua (Sirius), the brightest star in the night sky, rises in the east-south-east, like the Sun at the summer solstice; Matariki (the Pleiades Cluster) rises in the east-north-east, like the Sun at the winter solstice; Tautoru (Orion's Belt) rises due east, like the Sun at the equinoctes. Te Punga, the Southern Cross, skirts the southern horizon as it reaches its lowest point in the night sky. It is sometimes seen as the anchor of the Waka (canoe) of Tamarereti, who sailed across the sky placing Ngā Whetū (the stars) across the body of Ranginui. The Diamond Cross and False Cross asterisms can also be seen low in the south, and the bottom star of the Diamond appears slightly fuzzy due to its being surrounded by a cluster of dimmer stars. Between these crosses lies the Carina Nebula, in which binoculars or a telescope can pick out swirls of luminosity and star clusters. Eta Carinae, one of the most massive stars known, is beside the nebula. The star Achernar is high above the Southern Cross, and between the two are the Magellanic Clouds, dwarf galaxies near to the Milky Way. The bright globular cluster 47 Tucanae is nearby in the sky, in the constellation of Tucana, the Toucan. Alpha Tucanae is a yellow giant star of magnitude +2.8, while Beta Tucanae is actually a group of six stars which seem to be loosely bound together by gravity.

The Leonid meteor shower occurs this month, and is best observed about three hours before sunrise from the 15th to the 17th. It originates from dust shed by Comet Tempel-Tuttle as it comes close to the Earth every 33 years. Its shooting stars appear to come from Leo the Lion, a constellation marked by a sickle shape that represents the chest and head.This year's shower coincides with a full Moon, hampering viewing.

The constellations of Orion and Taurus are visible from all over the Earth, because they straddle the celestial equator. Rigel, Orion's brightest star, is one of the Hunter's feet, but is at the top as seen from the southern hemisphere. It has a companion star, Rigel B, which is usually lost in the glare of Rigel even though it has a magnitude of +6.7 and would otherwise be visible in binoculars. Rigel is called Puanga by Māori, and its dawn rising over the lower North Island of New Zealand heralds the new year. Betelgeuse, one of Orion's shoulders, is a bright red giant star which is cooler than the Sun because it is swollen by the fusion of helium at its core as it nears the end of its life. Taurus is next to Orion, and is currently on the opposite side of the sky to the Sun, which is now in the lesser known constellation of Ophiuchus.

Comet ISON will hopefully brighten to naked-eye visibility this month. It swings past the Sun on the 28th and 29th of November, passing just over one million kilometres from it. It may be best seen after perihelion, when it crosses into the northern hemisphere sky.

Odds and Ends

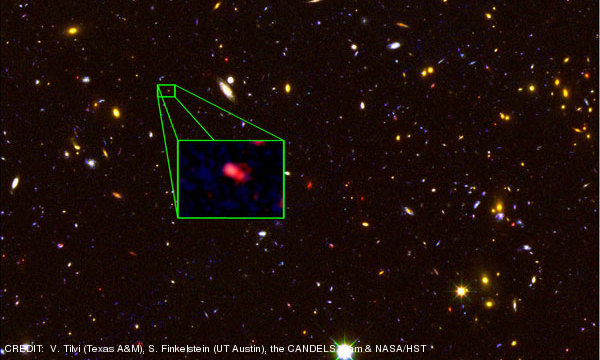

A galaxy more distant than any other yet observed has been discovered. Z8_GND_5296 formed within 700 million years of the beginning of the universe, and is about 13.1 billion light-years away. Discoveries like this are exciting because they give astronomers the opportunity to study galaxies as they were in the early universe. Z8_GND-5296 has an unusually high rate of star formation, a characteristic it shares with the previous record-holder for the most distant galaxy. An article on the new discovery was published on SPACE.com on October 23rd.

Space tourism is set to get ever so slightly more accessible in the next few years if a new company, World View Enterprises , succeeds in its plan to offer balloon rides to the edge of space, 30 km (19 miles) up into the atmosphere. At this altitude, the blackness of space and the curvature of the Earth are visible, even if the 'official' boundary of the atmosphere is 100 km (62 miles) up.

NASA Scientist Dr. Harold White is working on creating space warp bubbles,which would potentially allow faster than light space travel. The idea was first proposed by Miguel Alcubierre in 1994 and is similar to the warp drive technology used on board the Star Ship Enterprise! The Alcubierre drive required the existence of exotic matter and large amounts of energy to warp space, but Dr. White and his colleagues are working on methods which would reduce these energy requirements. They aim to test their technology by warping the space around photons.

Show Credits

| News: | Stuart Harper |

| Interview: | Indy Leclercq and Clive Tadhunter |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and John Field |

| Presenters: | Cat McGuire, Fiona Healy and Indy Leclercq |

| Editors: | Indy Leclercq, Sally Cooper, Francesca Lucini and Mark Purver |

| Segment Voice: | Mike Peel |

| Website: | Indy Leclercq and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Indy Leclercq |

| Cover art: | Hubble space telescope image of the most distant galaxy ever seen, Z8_GND_5296 |

[an error occurred while processing this directive]