In the show this time, we talk to Prof Andrew Jaffe about probing the early universe with Planck, Stuart rounds up the latest news and we find out what we can see in the October night sky from Ian Morison and John Field.

The News

This month in the news we get to the core of the matter:

At a distance of 24,000 light years from the Earth, in the direction of Sagittarius A*, is the small region of space which resides at the center of the Milky Way. The Galactic center contains some of the most violent and extreme physical processes we can observe and squashes them into a region only a few hundred light years across. However observing the Galactic center with light we see with our eyes is impossible because it is obscured by thick curtains of dust, instead, what we know of the Galactic center comes from observations using radio and X-ray telescopes. From these observations we have learnt that the Galactic center contains several of the largest star forming nebulae within the Milky Way, a powerful magnetic field that forms long filaments of gas and dust and most importantly at the very core is a dark object four million times the mass of the Sun, a super massive black hole.

The super massive black hole at the center of the Milky Way is the closest of its kind, the next nearest residing presumably within the core of Andromeda more than one hundred times further away. This makes the Milky Way's black hole an excellent laboratory for studying the properties of black holes. Although black holes are poorly understood phenomena we believe they are a critical component in the formation of galaxies and that how they behave at any given time has a profound effect upon the rest of the host galaxy. Super massive black holes can be both dormant, like the one in the Milky Way, or incredibly bright as it feeds upon the gas, dust and stars within a galaxy. Though what causes a black hole to stop or start feeding is not understood. For example by using X-ray observations it is possible to see that the super massive black hole in the center of the Milky Way is surrounded by a disk of hot gas, yet this gas is not being consumed by the black hole. One reason why this may occur is related to the extremely powerful magnetic field generated by the black hole which interacts with the surroundings in such a way as to keep anything from falling past the black holes event horizon.

The magnetic field generated by the Milky Way's super massive black hole is a key component to understanding the Galactic centers environment and our understanding of how super massive black holes stop or start consuming matter within a galaxy. Although measuring the magnetic field directly is not possible a group of astronomers working with many telescopes, at many different wavelengths, have been able to measure the effect the magnetic field has on the light emitted from a pulsar that resides near to the super massive black hole. The light from a pulsar is highly polarised and when it passes through the thick clouds of plasma and the strong magnetic field in the Galactic center the orientation of its polarisation rotates. The amount of rotation depends on the distance traveled and the wavelength of light observed. Thus the astronomers, using many different observations at different wavelengths, were able to determine exactly how strong the magnetic field around the pulsar is and therefore infer the strength of the magnetic field around the super massive black hole. This will allow for the feeding habits of the super massive black hole to be better understood and if more pulsars can be found near the black hole this method could be used to test its space-time properties.

Also in the news: The rate at which new stars are formed every year throughout the universe long ago reached its peak. Today the only places where new stars are forming are within the cold, dense clouds of spiral galaxies, like the Milky Way, but at a paltry rate of just 1 or 2 a year. In the past, roughly 10 billion years ago, it was possible to have galaxies forming thousands of stars a year. However with so many stars forming, and consequently dying, huge injections of energy heated up and blasted away the gas and dust within the galaxies. In time the galaxies were left with nothing more to form new stars and slowly aged into the large, red elliptical galaxies we see throughout the universe today.

This though is not the complete story because if it was we would see that relationship between the mass within a galaxies halo, the tenuous bubble of gas and dark matter that surrounds all galaxies, and the number of stars within a galaxy having an obvious link. This is because the expectation would be that if there is more stuff to make stars, there should be more stars. This is not the case. Instead we see far more dim galaxies with few stars than we see of galaxies with low mass halos. So what is stopping the formation of stars? The culprit is once again, the super massive black hole at the core of these galaxies. How exactly a super massive black hole stops star formation though is still a mystery. The primary line of thought is that the powerful jet that is fired from either pole of the black hole smashes through the star forming material in the galaxy, heating it up and ejecting it into intergalactic space. Unfortunately though this would not be enough to quench star formation within a galaxy because the beam of the jet is so narrow only a tiny sliver of star forming material would be caught within it.

Last month astronomers proposed a new way in which super massive black holes can quench star formation. They made super high resolution radio telescope observations of a nearby galaxy 4C12.50 which has an actively feeding super massive black hole in its galactic core and thus a powerful jet emerging in opposite directions from the galaxy. What the astronomers hoped to do was measure individual nebulae within 4C12.50 and see how much radio emission from the jet is being absorbed. What they found was that some of the clouds they were observing were casting long radio shadows as they absorbed nearly all of the jets emissions. Then by making further observations they could measure the velocities of these clouds relative to 4C12.50 and they found that many of them were traveling in excess of 1000 kilometers per second. Such furious speeds means that the gas within the nebula will never be able to form stars, as that requires cool, calm environments with very little kinetic energy so that the mutual gravitational attraction of all the gas can dominate. These findings now confirm super massive black holes are key to galactic evolution and the emergence of the long dead elliptical galaxies we see throughout the universe.

Interview with Andrew Jaffe

Prof. Andrew Jaffe from Imperial College London talks to us about probing the early universe with Planck. He begins by telling us what he means by the "early universe" and how we observe it, especially the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), and how maps of the CMB are produced from what Planck initially observes. He discusses the science that can be obtained from these observations, including temperature fluctuations and patterns in the CMB and, in the future, the polarisation of the CMB and why polarisation is important. He goes on to tell us about how these observations can be used to constrain models of the Universe and what we hope to gain from this in the future.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during October 2013.

Cygnus, with its bright star Deneb, is high overhead in the evening. Lyra, containing the star Vega, is nearby. The star Altair, in Vega, completes the Summer Triangle. Hercules in lower to the west, with its four brightest stars making the Keystone. Two-thirds of the way up the right-hand side of the Keystone is the globular cluster M13. Pegasus is in the south-east. The constellation of Andromeda, hosting the Andromeda Galaxy, is nearby. The Milky Way runs down towards the north-east, along which can be found Cassiopeia and Perseus. In between these two constellations is the Double Cluster, which can be seen with the naked eye but looks spectacular in a telescope. Taurus and the Pleiades rise later in the evening.

The Planets

- Jupiter is well placed in the pre-dawn sky, but rises around midnight BST (British Summer Time, 1 hour ahead of Universal Time) at the beginning of the month and 22:00 at the end. It is 40° above the the south-eastern horizon in Gemini as twilight begins, shining at magnitude -2.2 and with a disc 38" across. It is 90° from the Sun in the sky on the 12st, giving a good opportunity to observe eclipses and shadow transits of the Galilean moons. Jupiter brightens to magnitude -2.4 by the end of the month, and has a disc 41" across.

- Mars is in Leo, rising four to five hours before the Sun. It has a magnitude of +1.6 and its angular diameter increases from 4.4 to 4.9" during the month, so that surface features begin to become visible to a telescope. It is close to the star Regulus on the 12th, making a nice colour contrast. Comet ISON also appears near to Mars from the 16th to the 19th.

- Saturn is in Libra, and may just be visible above the south-western horizon after sunset in the first half of the month, not far from Venus. Its magnitude is +0.7 and it has an angular size of 15.5". The planet's northern hemisphere is visible, while the southern hemisphere is largely hidden by its rings, and its largest moon, Titan, may be visible using a telescope - but don't use it until the Sun has set.

- Mercury is below Saturn, and barely distinguishable in the evening twilight. The two planets will be joined by a slender crescent Moon on the 7th.

- Venus brightens from -4.2 to -4.4 in magnitude during October, while moving from Libra to Scorpius and then into Ophiuchus. It enters Sagittarius on the 1st of November, when it is also at greatest eastern elongation. It grows from 18 to 25" over the month, while its percentage illumination drops from 73 to 50%.

Highlights

- Venus, Saturn, Mercury and a thin crescent Moon are just about visible together about 45 minutes after sunset on the 8th.

- Mars is very close to Regulus on the14th, showing up red next to the blue of the star.

- Neptune can be observed through a small telescope this month, and can be found in Aquarius at magnitude +7.9. It reaches a maximum elevation of 27°. Its largest moon, Triton, may be observed on a clear night using a telescope of 8 inches or more in aperture.

- Comet ISON should become visible to medium-sized telescopes this month. It is just above Regulus in Leo on the 16th, when it is also close to Mars. It is not brightening as quickly as hoped, so it is not clear whether it will become as spectacular as first predicted.

Southern Hemisphere

John Field from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during October 2013.

October sees Scorpius and Sagittarius in the western sky after sunset, and these constellations begin to set around midnight New Zealand Daylight Time (NZDT, 13 hours ahead of Universal Time). The Milky Way runs north to south in the evening, and covers the western horizon by midnight. On the 5th, the lack of moonlight gives the best chance of observing the zodiacal light in the west. This faint, triangular glow can be seen after sunset, and is caused by sunlight reflecting off dust particles in the plane of our Solar System. The planet Saturn and the star Spica are low in the west, and will soon be lost in the twilight sky. Venus is high in the evening sky, with a crescent Moon joining it on the 8th. It will be close to the red star Antares on the 17th, in the constellation of Scorpius. Both Uranus and Neptune are in the evening sky, but are too faint to spot with the naked eye.

The brightest star currently visible in the evening, Canopus, is in the south-east and climbs higher in the southern sky during the night. While low down, it twinkles in a variety of colours due to the passage of its light through our turbulent atmosphere. To Māori the star is Atutahi, the high chief of the heavens. Sirius, the only star which outshines Canopus at night, rises after midnight. At this time Alpha Centauri, the third-brightest night-time star, is also in the sky. All three appear along the Milky Way, and Alpha Centauri is the brighter of the two stars that point towards Crux, the Southern Cross. While appearing to the unaided eye as a single yellowish star, a small telescope reveals that it is a binary system. Its component stars take 80 years to orbit around one another. Crux gets lower in the sky during the evening and is close to the horizon at midnight, but never sets over New Zealand. Travelling along the Milky Way from the pointers and Crux, we come to the Carina Nebula, a vast star-forming region which appears as a bright haze in the sky. Binoculars or a small telescope show dark lanes and star clusters among numerous stars. One of the most massive stars in the Galaxy, Eta Carinae, sits within this nebula. It is bright orange and has brightened over the last 20 years to become visible to naked eye. The two Magellanic Clouds are high in the south, near the bright star Achernar. They are irregular dwarf galaxies relatively close to our own Milky Way, and look like fuzzy clouds moving around the southern celestial pole. Very low in the north is our nearest neighbouring giant galaxy, Andromeda. It is faintly visible to the eye and can be easily seen in binoculars if the sky is dark.

Jupiter rises around 03:00 NZDT early in the month and is low to the north at sunrise, while Mars appears as a red 'star' in the morning twilight. Comet ISON is now rapidly approaching the Sun and passes by Mars and the star Regulus in the sky this month. It is below and to the north of Mars for the rest of October, probably becoming visible to binoculars - and perhaps even to the naked eye - by month's end. Next month, it will make its closest approach to the Sun.

Odds and Ends

The Kepler space telescope may not have reached the end of its life quite yet! As touched on previously in the Jodcast, the space telescope can't search for exoplanets any more due to faulty stabilisation components. NASA has since put out a call for ideas on how to use the telescope in its current state, interesting stellar astronomers.

The Mars rover Curiosity has detected water! By examining a pinch of dirt the scientists found the dirt contained 2% water by mass. This holds huge implications for man missions as there is a large source of water already there.

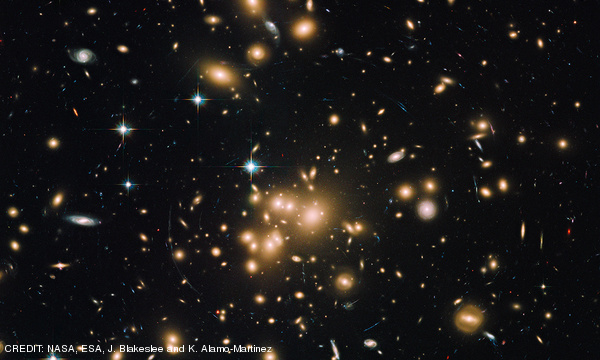

Back in 2003, the Space Telescope Science Institute released Hubbleglobular clusters, most of which are found around the large elliptical galaxy in the core of Abell 1689. For comparison, the Milky Way contains about 150 galaxies. Moreover, the group found that more globular clusters are found in locations with more dark matter, which implies that they form more effectively in these regions. More information can be found here .

Warning: some links may not work due to the US Government shutdown!Show Credits

| News: | Stuart Harper |

| Interview: | Christina Smith and Andrew Jaffe |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and John Field |

| Presenters: | George Bendo, Indy Leclercq and Chris Wallis |

| Editors: | Mark Purver and Sally Cooper |

| Segment Voice: | Mike Peel |

| Website: | Indy Leclercq and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Indy Leclercq |

| Cover art: | Hubble Wide-Field Image of Galaxy Cluster and Gravitational Lens Abell 1689 CREDIT: NASA, ESA, J. Blakeslee and K. Alamo-Martinez |

[an error occurred while processing this directive]