In the show this time, we talk to Prof David Kirkby about measuring the universe with cosmic sound, Stuart rounds up the latest news and we find out what we can see in the September night sky from Ian Morison and John Field.

The News

This month in the news: Gamma-Ray Bursts and Flickering stars.

In the midst of the cold war, the Vela satellites were watching for evidence of nations violating the Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty by detonating nuclear weapons in the Earth's atmosphere or in outer-space. The event they were looking for was the characteristic gamma-ray burst that occurs when a nuclear weapon explodes. However between 1969 and 1972 they detected 16 gamma-ray bursts that appeared to be originating from a source not of the Earth. These gamma-ray bursts were the first observations of the single most energetic event that can occur in the universe, the origin of which we still do not completely understand to this day.

Gamma-rays are a very energetic form of light. For example we can see with our eyes optical light from red to blue, blue being the highest frequency and the most energetic. If you were to increase the frequency of blue light, giving it more and more energy, it would first become ultra-violet, then x-rays and then finally gamma-rays. A gamma-ray burst then is a short flash of these extremely energetic rays of light that may last only a few milliseconds or up to a few tens of seconds. Even so for the duration of their short lives gamma-ray bursts are the brightest event in the Universe and the briefer their life the brighter they are, the shortest gamma-ray bursts being briefly one hundred thousand times brighter than a supernova.

Since the Vela satellites we have learnt a lot more about gamma-ray bursts. For example we know that after the initial burst the object from which the burst originated will have an afterglow that for days after will shine with the full spectrum of light, from x-rays to radio waves. We also know that the longer gamma-ray bursts, of a few seconds or more, originate from the core of an exploding star upon the moment it goes supernova. However the cause of the shortest gamma-ray bursts are still a mystery. One reason for this is that the shortest gamma-ray bursts are so powerfully energetic that we simply cannot explain how they can occur without using extreme astrophysical scenarios such as the collision of two neutron stars to form a stellar mass black hole. Such events are poorly understood, in part because they are incredibly complicated but also because they have never been observed.

As mentioned earlier, gamma-ray bursts are followed by a long afterglow. The cause of the afterglow is thought to be related to an expanding shell of radioactive material that is blown out from the initial collision of the two neutron stars that caused the burst. As the radioactive material decays it will give off light, from x-rays radiowaves, that we detect on Earth. This event is known as a kilonova. A kilonova is also expected to appear in optical and infrared light as a short lived and much dimmer supernova. Last month astronomers using numerous different telescopes, including the Swift, Herschel and Hubble telescopes, believe they may have made the first detection of a kilonova in both infrared and optical. By quickly reacting to the detection of a gamma-ray burst they were able to observe the kilonova from its very beginning. Then by measuring how the brightness of the kilonova changed over many days have been able to match the observations with predictions. This means that they could have made the first direct observation of a two neutron star collision but to be sure they will need to have more observations of other kilonovas. If they are correct though, short gamma-ray bursts and their subsequent kilonovas could become the basis of future astronomical experiments because they could be used to test for the existence of gravitational waves and probe the very early universe.

Also in the news, when we see stars in the night sky we can see them twinkling and changing rapidly as the atmosphere jostles around the light as it travels towards our eyes. These changes having nothing to do with intrinsic nature of the star and if we were to be viewing the stars from space we would see them as stable points of light. However if our eyes were more sensitive we would see that they are not stable at all but are constantly undergoing variations in their brightness on all kinds of timescales, be it minutes, hours or days.

By observing the changes in the brightness from the surface of a star it is possible infer the strength of its gravitational field. This technique is called astroseismology. Traditionally astronomers will watch for the effects of large scale changes in the brightness that occur over course of days. These variations in brightness are typically related to the stars magnetic field and manifest as dark blemishes on the surface known as sunspots. However these sort of observations are limited to space based telescopes because, as mentioned at the start, the light is changed too much by traversing the atmosphere to be able to measure the changes in brightness accurately using ground based telescopes. Satellites like Kepler then are required by astroseismologists to make their measurements. Unfortunately observing time with satellite based telescopes is very competitive and the long observations required to make accurate measurements of the gravitational field from brightness variations of stars can can only be afforded to a few sources.

Fortunately new research by a team of astroseismologists have uncovered a potential new way of measuring a stars gravitational field in a fraction of the time. This is done by measuring the 'flicker' of the star, very fast variations in the stars brightness caused by convective currents beneath the surface. What they did was to re-observe stars whose gravitational field had already been well established using the old technique. Then they would compare the old result for the gravitational field of the stars with the one they measured from each stars 'flicker' variation. What they found was the new technique agreed very closely with the results of the old technique. With this encouraging result they now hope that in the future they will be able to measure the 'flicker' variation of many stars of all different kinds without having to steal observing time from other astronomers.

Interview with David Kirkby

Prof. David Kirkby tells us about measuring the Universe with cosmic sound. Cosmic sound isn't really a sound you can listen to, but more of a 'scientists definition' of sound. These 'sound waves' were created by the Big Bang but only lasted a short time. At the point the universe began to change phase, the 'sound waves' got frozen in. These sound waves allow Prof. Kirkby to examine the expansion history of the universe. He goes on to tell us how it is possible to measure these 'frozen sound waves' in the universe from the jumble of information we get from observations, and what the future holds for this field.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during September 2013.

The bright star Deneb is high in the evening sky, with Vega nearby and Altair lower down forming the Summer Triangle. The asterism of Brocchi's Cluster, or the Coathanger, lies a third of the way up from Altair towards Vega in front of the dark region of the Milky Way known as the Cygnus Rift. Below is the small constellation of Delphinus the Dolphin. Pegasus is rising in the east, next to Andromeda and M31, the Andromeda Galaxy. To find M31, begin at the bright star Alpha Andromedae (Alpheratz) at the top-left corner of the Square of Pegasus, move one star to the left, curve slightly to the right to a second bright star, then take a right-angle to the right, pass a fairly bright star, and move the same distance again to reach the milky glow of the galaxy. Above Andromeda is the W-shaped Cassiopeia, whose lower V-shape also points towards M31. Perseus is lower down in the east as the evening wears on, and between Perseus and Cassiopeia is the Perseus Double Cluster, a pair of star clusters that look lovely in a telescope.

The Planets

- Jupiter is beginning a superb apparition. It lies in Gemini, and will reach above 60° in elevation when it reaches opposition early next year. At the beginning of September, it rises around 01:00 BST (British Summer Time, one hour ahead of Universal Time) and is 25° above the south-eastern horizon at morning twilight. By the end of the month, it rises at 23:30 BST and is at 50° elevation by dawn. It brightens from magnitude -2 to -2.2 over the month, and its angular diameter increases from 35 to 37.5". A small telescope easily shows the four Galilean moons, the Great Red Spot and the North and South Equatorial Bands.

- Saturn is in Libra, and lies low in the west after sunset at magnitude +0.7. Its angular size drops from 16.1 to 15.6" during the month. The rings are around 17° from the line of sight and the planet's southern hemisphere is visible. Its largest moon, Titan, may be visible with a telescope.

- Mars is beginning its apparition, starting the month in Cancer and moving into Leo on the 25th. It rises at about 03:00 BST at magnitude +1.6, and lies some 12° above the north-eastern horizon at 04:30. You may need binoculars to see it, but don't use them once the Sun is up. Mars's angular size increases from 4.1 to 4.4" during the month, but it will remain difficult to see any surface markings.

- Mercury may be just visible above the horizon half an hour after sunset at the end of the month, below Venus and Saturn. With a magnitude of -0.1, binoculars or a telescope are required to see it against the light of dawn.

Highlights

- Saturn and Venus appear alongside a thin crescent Moon about 45 minutes after sunset on the 8th and 9th, given a low west-south-western horizon.

- Four nice objects can be observed in the southern sky this month: the globular cluster M13 in Hercules, the Double Double Star in Lyra and the planetary nebulae called the Ring and the Dumbbell in Lyra and Vulpecula respectively.

- Low in the west-south-west, Saturn is almost directly above Venus one hour after sunset on the 17th, the latter being brighter at magnitude -4.1.

- Mercury joins Saturn and Venus 30 minutes after sunset on the 24th, with Mercury just 0.75° from the bright star Spica, in Virgo. Comet ISON appears in the morning sky around the 27th. A six-inch or larger telescope may allow you to spot it. It had a magnitude of +14.3 on the 12th of August - fainter than previously expected. On the 27th itself, ISON is 2° from the planet Mars.

Southern Hemisphere

John Field from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during September 2013.

As the spring equinox approaches on the 22nd, the winter stars set earlier in the west and the summer constellations begin to rise in the east. Scorpius is overhead after sunset. To Māori it is a fish hook, while to the chinese it is a dragon breathing out the Milky Way. The constellation contains many bright stars, double stars and star clusters. The Milky Way runs north to south and provides a wealth of targets. Cygnus the Swan, or the Northern Cross, is in the north with its neck stretching along the Milky Way and its brightest star, Deneb, marking the tail on the horizon. The stars Deneb, Vega and Altair form the Winter Triangle. Beta Cygni marks the Swan's head, and its alternative name, Albireo, derives from 'beak star'. With a magnitude of +3, a telescope show it to be a lovely double star, with gold and blue components. Gamma Cygni is the chest of the Swan and the centre of the Cross, shining at magnitude +2.6. A dark band on the Milky Way, known as the Cygnus Rift, can be spotted on a moonless night. Sometimes called the Northern Coalsack, it is a large cloud of dust around a million times the mass of the Sun. North-east of Deneb is the open cluster M39, larger than the full Moon and visible to the unaided eye. Binoculars or a wide-field telescope reveal a loose, triangular cluster of over 30 stars.

The bright star Fomalhaut is near the eastern horizon, forming the mouth of Piscis Austrinus, the faint constellation of the Southern Fish. Between Fomalhaut and Altair is the long string of stars making up the zodiacal constellation of Aquarius, the Water-carrier. Its second-brightest star is Alpha Aquarii, while Beta Aquarii is very slightly brighter at magnitude +2.87. Zeta Aquarii, at magnitude +3.6, is a double star which crossed the celestial equator into the northern sky in 2004. Nearby are the globular cluster M2, a hazy star to binoculars but partially resolvable with a 20-centimetre telescope, and NGC 7293, a nearby planetary nebula known as the Helix Nebula which can also be resolved with a telescope. Crux, the Southern Cross, nestles in the Milky Way midway down the south-western sky, with the two pointer stars following behind. The Jewel Box, a 4th-magnitude haze to the naked eye, appears as a lovely star cluster in binoculars beside the second-brightest star in Crux. It is partially obscured by a cloud of dust called the Coalsack Nebula. Canopus, the second-brightest night-time star, moves along the southern horizon.

The planets Venus and Saturn are in the west after sunset, and are joined by Mercury early in the month. The Moon sits between Saturn and Venus on the 9th, while Mercury is near to the bright star Spica on the 25th. Venus moves past Saturn during September, setting around 23:30 NZST (New Zealand Standard Time, 12 hours ahead of Universal Time) by month's end. Saturn moves closer to the Sun, setting earlier and becoming fainter. Jupiter climbs high into the morning sky, while Mars hides in the early-morning twilight. The summer constellations of Taurus, Orion, Canis Major and Canis Minor shine above Jupiter.

Odds and Ends

Last month marked the 10th anniversary of the launch of the Spitzer Space Telescope. In the 10 years of the telescope's existence, it has performed multiple groundbreaking observations. Even though it ran out of coolant for its mid- and far-infrared instruments, it can still make images at 3.6 and 4.5 microns. More details as well as some of the more interesting images from the mission are available from NASA's press release here

The Kepler space telescope has had to finally cease operations due to a second faulty reaction wheel that stabilise the telescope. The wheel broke down in May, and NASA engineers have tried but ultimately failed to find a workaround. The telescope was launched in 2009, and its primary mission was to search for earth-like exoplanets, which it has done very successfully: 135 new planets have been confirmed so far, and the telescope has collected data on 3,500 more candidates which have yet to be fully analysed – excitingly, scientists expect most of these will yield confirmed planets.

The Mars Curiosity Rover has driven on its own for the first time. Usually the rover gets instructions from Earth and carries them out, but there was a dip in its route. The total distance which couldn't be seen in advance of the rover driving into it was 33ft (out of the 141ft it travelled that day). It jinked to avoid something it determined was a hazard but had an otherwise uneventful route.

Show Credits

| News: | Stuart Harper |

| Interview: | Christina Smith and David Kirkby |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and John Field |

| Presenters: | George Bendo, Indy Leclercq and Christina Smith |

| Editors: | Indy Leclerq, Mark Purver and Christina Smith |

| Segment Voice: | Mike Peel |

| Website: | Christina Smith and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Christina Smith |

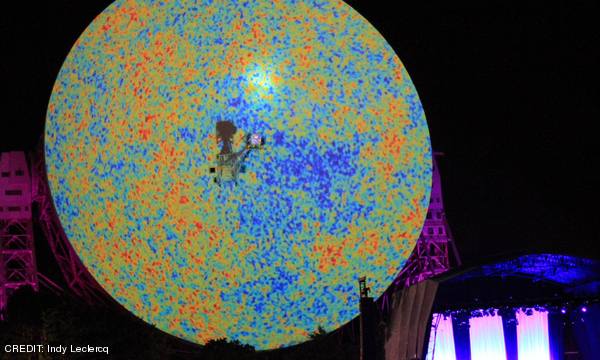

| Cover art: | The CMB projected into the Lovell Dish at Live from Jodrell Bank CREDIT: Indy Leclercq |

[an error occurred while processing this directive]