In the show this time, we have more interviews from the National Astronomy Meeting as Dr Simon Green tells us about collecting cometary dust with the Stardust-NExT mission and Dr Joseph Mottram talks about massive star formation. Stuart brings us the latest astronomy news and we find out about the September night sky from Ian Morison and John Field.

The News

In the news this month:

NASA's Kepler satellite last month continued to keep planet formation scientists busy by discovering Kepler-47, a star system unlike any other found to date. Kepler-47 is a binary star system; one of the stars is roughly like our own Sun and its companion is a faint dwarf star. Binary systems like this are expected to make up roughly one third of all the star systems in the Galaxy, but what makes Kepler-47 unique is that it has two stable orbiting planets. It was only last year (2011) that Kepler-16 was discovered - a binary system containing a single Jupiter-sized planet - and since then only five other planets have been found to orbit a binary star system. Also interesting to note about the planets Kepler-47b and Kepler-47c are their sizes and locations. The closest-orbiting planet, Kepler-47b, is expected to be 3 times the diameter of the Earth, and its partner, Kepler-47c, is a bit larger at 4.5 times the diameter. Their masses are, respectively, around 8 and 20 times that of the Earth's. This probably means they are similar to Uranus in dimension, but, most importantly, Kepler-47c lies comfortably within the habitable zone, the region around a host star in which it is expected that liquid water could exist on a planet's surface. This gives the exciting possibility that Kepler-47c could have a water-bearing moon.

Kepler currently has 77 planets within its catalogue of discoveries, but it will possibly be systems like Kepler-47 that prove to be the most useful for testing our understanding of planet formation. This is because Kepler-47 offers the opportunity to study a planetary system which, in the past, many might have thought to be impossible. In fact, not long ago it was expected that single-planet systems around binary stars would be very unlikely, so scepticism towards planetary binary star systems was not unreasonable. Questions of how planets can maintain stable orbits and not be flung into interstellar space or collide with other planets, when the gravitational forces acting upon them is constantly changing, are problems still to be resolved. Also, the question of how the planets formed at all in such a turbulent system is still open. However, at least now, with the discovery of Kepler-47, it is safe to assume that these questions do have answers.

A Type Ia supernova is the thermonuclear detonation of a white dwarf star that has exceeded the Chandrasekhar limit of about 1.4 solar masses, resulting in a runaway fusion process in the core of the star. Type Ia supernovae are critical for many aspects of astronomy as they are extremely bright and always release similar amounts of energy. This makes them ideal for calculating distances to remote star-forming galaxies that may be hundreds of millions of light years away. However, when measuring such vast distances, even small errors in our understanding of what causes a Type Ia supernova can result in radically different interpretations for galaxy formation theories.

The expected progenitor star system for a Type Ia supernova involves a white dwarf orbiting a large red giant star from which the white dwarf can siphon mass. However, this system may not always result in a supernova since it is possible that the hydrogen gas being pulled from the surface of the red giant onto the white dwarf may undergo runaway nuclear fusion in the thin shell of enveloping accreted material. This sort of thermonuclear explosion is known as a nova and is significantly less luminous than a supernova, but, most importantly, it is thought that the nova explosion will remove more mass from the white dwarf than it gained from its companion star. Each nova therefore pushes the white dwarf safely away from the critical Chandrasekhar limit and prevents it from going supernova.

Unfortunately for white dwarfs, nova explosions may not save them from going supernova, as researchers using the 48-inch Samuel Oschin Telescope at the Palomar Observatory found last month. Using a method which allows the Telescope to observe a large portion of the sky in real time, they were able to detect a Type Ia supernova, named PTF 11kx, and very rapidly take spectroscopic measurements to determine the structure of the explosion. They found that the supernova detonation was surrounded by an expanding gas shell that was too slow to be from a different, older supernova but far too fast to be a stellar wind from the red giant companion star. They propose that it could be the remnant of a smaller nova explosion, perhaps originating from the white dwarf which had just gone supernova. By calculating the velocity of the expanding supernova and the slower nova remnant, they estimated the expected time both would meet if both originated from the same white dwarf. Their estimates were right, meaning PTF 11kx had at least one nova explosion in its history before going supernova. This shows that, although all Type Ia supernovae may be similar, they can come from very different beginnings.

And finally: researchers using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have measured the presence of simplest form of sugar, glycolaldehyde, around a binary young stellar object near the massive star-forming molecular cloud Rho Ophiuchi. This is not the first detection of glycolaldehyde, but previously it has only been seen in the cold, dense cores of star-forming clouds containing many large, hot young stars. The star around which ALMA has detected glycolaldehyde is very similar to our own Sun in terms of size.

The implications of finding sugars around Sun-like stars is strongly related to the story of how life may evolve in the Universe. Simple sugars are the building blocks needed to form the more complex molecules required for life (as we know it), such as ribose, RNA and then finally DNA. The researchers ask what proportion of these complex molecules can form in the environment around young stars and whether they will they survive to the planet-forming stage. For now, the answers to these questions seem quite positive as the sugars are found to be falling into a region around the star where it would be expected that, in the future, planets will form.

Interview with Dr Simon Green

Dr. Simon Green of the Open University is a member of the Stardust-NExT mission. Stardust collected samples of cometary dust during its close flyby of Comet Wild 2 in January 2004. Stardust-NExT is a follow-on mission for Stardust, in which it completed a flyby of comet Tempel-1 on the 14th of February 2011 to observe the crater left over from the Deep Impact mission.

Interview with Dr Joseph Mottram

Dr. Joseph Mottram from Leiden Observatory talks to us about massive star formation and how this differs from the formation of low- and intermediate-mass stars. He discusses the time scales of formation for stars and stellar clusters.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during September 2012.

As the nights lengthen, the turning of the year moves the stars eastward so they are seen earlier in the evening, resulting in a similar sky just after sunset for much of the month. Hercules is setting in the west after dark. Its four brightest stars comprise the Keystone, and about two thirds of the way up the right-hand side is the globular cluster M13. The Summer Triangle, consisting of the stars Vega, Deneb and Altair, dominates the southern sky. About a third of the way from Altair towards Vega lies the Cygnus Rift, a dark region containing the asterism Brocchi's Cluster. Up and to the left of this is Albireo, the faintest of the four stars making up the Northern Cross within Cygnus. It is a double star, and a telescope will show the two stars to be respectively golden and turquoise in colour. The tiny constellation of Delphinus, the Dolphin, is down and to the left of Cygnus. Pegasus, much larger, is over in the east, with Andromeda up to its left. Andromeda gives its name to both a constellation and our nearest neighbouring large galaxy, which lies beyond the stars in the same direction. You can find the Andromeda Galaxy by 'star-hopping': start at Alpheratz, the top-left-hand star in the Square of Pegasus, then go one bright star to the left and fork right to the next bright star. Go sharp right to the next bright star, then continue onwards the same distance again, and you should find the fuzzy glow of Andromeda using binoculars. In a very dark sky, it can be seen with the unaided eye. The W-shape of Cassiopeia is above Andromeda. Meanwhile, Perseus is rising in the east. In between Cassiopeia and Perseus, a pair of open star clusters called the Perseus Double Cluster lies on the Milky Way.

The Planets

- Jupiter rises around midnight BST (British Summer Time, one hour ahead of Universal Time) at the beginning of the month and around 22:00 BST at the end. It is best seen before dawn, when it reaches 60° elevation in the constellation of Taurus. It is 6.5° up and to the left of the star Aldebaran, the Eye of the Bull, at the beginning of September, and has a magnitude of -2.3. It moves towards the Bull's horns during the month, and brightens to magnitude -2.5. Its angular size increases from 39 to 43" as it gets closer to Earth, allowing a small telescope to pick out surface detail, as well as the four Galilean moons.

- Saturn is coming to the end of its current apparition, but can still be seen low in the west after sunset, shining at magnitude +0.8. The disc is 16" across, and the rings, inclined at 14° to the line of sight, span 36".

- Mercury is too close to the Sun to be easily spotted this month.

- Mars is not far from Saturn and moves eastward through Virgo and Libra during the month. Its angular size drops from 5.2 to 4.8", so it is past its best and surface detail is difficult to make out, although the pink disc is still visible. Its elevation as darkness falls is 8° at the start of the month, and decreases thereafter.

- Venus rises about 3 hours before the Sun and dominates the pre-dawn sky at around magnitude -4.2. Moving rapidly eastwards, it makes its way from Gemini, at the beginning of September, into Cancer on the 4th, and then into Leo on the 23rd. At the end of month, it is 3.5° up and to the right of the star Regulus. Its angular size drops from 20 to 16" while its illumination increases from 58 to 70%, so its magnitude changes only slightly, from -4.3 to 4.1.

Highlights

- Jupiter is close to a third-quarter moon on the 8th, in Taurus.

- Mars, at magnitude +1.2, is just to the left of a thin crescent moon on the 19th, although you will need a low western horizon to see it. Saturn, at magnitude +0.8, is to their right. You might spot earthshine on the dark part of the Moon, if clouds on the Earth reflect enough light to illuminate it.

- The planet Uranus makes its closest approach of the year to Earth on the 29th, and will be due south around midnight at magnitude +5.7. It will be easier to spot from the 12th to the 19th, however, as the Moon will not wash it out. It appears very close to the star 44 Piscium around the 21st, and, as star and planet have very similar brightnesses, they will look like a double star, with Uranus the bluer of the two. Their closest point comes around midday BST on the 23rd, with a separation of just 0.7', and is referred to as an 'appulse'.

- Venus is very close to Regulus on the 30th, in Leo, and gets even closer at the beginning of October.

- The Moon's Alpine Valley is nice to look at on 6th and 7th or the 23rd and 24th, when its proximity to the terminator casts sharp shadows. It cuts across the Apennine mountain chain at the edge of the Mare Imbrium. The Valley is about 79 miles long and 7 miles wide; a rille runs along the centre, but requires good seeing in order to be spotted. You can find out what the Moon will look like at any time by using the free computer programme Virtual Moon Atlas.

Southern Hemisphere

John Field from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during September 2012.

At the spring equinox on the 23rd, day and night are of approximately equal length. The constellations of Scorpius and Sagittarius are in the west after sunset. The red giant Antares, the Scorpion's Heart, is the brightest star in Scorpius. Eventually, it will exhaust its fuel and collapse under its own gravity, exploding in a supernova and leaving behind a neutron star or black hole, as well as scattering heavy elements into space. In Māori star lore, the line of stars from Antares to the Scorpion's tail is called Te Matau a Maui - the Hook of Maui. The Milky Way is broad and bright in this part of the sky, because we are looking towards to centre of the Galaxy. Clouds of interstellar dust make dark patches in the Milky Way and obscure the Galactic centre. They consist of ancient hydrogen and helium, as well as heavy elements produced by stars, and some will form new stars and planets one day. At the right-angle in the Scorpion's tail lies the open star cluster NGC 6231, with seven relatively bright stars. The cluster M7 is visible with the naked eye to the right of the tail, and is beautiful when viewed through binoculars or a telescope. M6, the Butterfly Cluster, is nearby but is fainter. Long-exposure photographs will reveal the colours and details of a number of star clusters in this region, along with nebulae and the Milky Way itself. Sagittarius, the Archer, is also sometimes called the Teapot, and the centre of our Galaxy lies below its spout. Infrared telescopes allow astronomers to see through the dust to the stars in the centre, whose orbits give away the presence of a black hole of over 4 million times the mass of the Sun. Below Sagittarius is M8, the Lagoon Nebula. It is a cloud of gas heated by young stars and containing dark dust lanes. Not far away is M20, the Trifid Nebula, a bright cloud dissected by three dark lines. As well as nebulae and open star clusters, this region of the sky contains globular clusters, which look like fuzzy spots. These collections of old stars are relics of the early ages of galaxies.

The Corona Australis, or Southern Crown, is near to Sagittarius. Travelling down the Milky Way towards the northern horizon, we reach Cygnus the Swan, a large cross-shaped constellation. Its brightest star, Deneb, marks the tail. Above and to the right is Aquila, the brightest star in Altair, while to its left is Vega, Lyra's brightest star and the fifth-brightest in the night sky. The three form the Winter Triangle for those in the southern hemisphere - the Summer Triangle for those in the north. By midnight NZST (New Zealand Standard Time, 12 hours ahead of Universal Time), Orion the Hunter and Canis Major, the larger of his dogs, are rising in the east as Scorpius and Sagittarius set in the west.

The Planets

- Saturn and Mars are seen setting in the west not long after sunset. They have now separated after their conjunction in mid-August. Saturn is near the star Spica, in Virgo, while Mars has moved northwards into Libra. NASA's Curiosity rover is now exploring the surface of Mars.

- Jupiter rises in the early morning and is in Taurus, near to the Pleiades, which are known as to Māori as Matariki.

- Mercury and Venus are poorly placed for viewing during September.

Highlights

- Two full moons occur for observers in New Zealand this month, on 1st and 30th. The second full moon in a month is known as a blue moon. Because of the time difference, observers in the UK see the first of these full moons at the end of August, so that one is the blue moon for them.

Odds and Ends

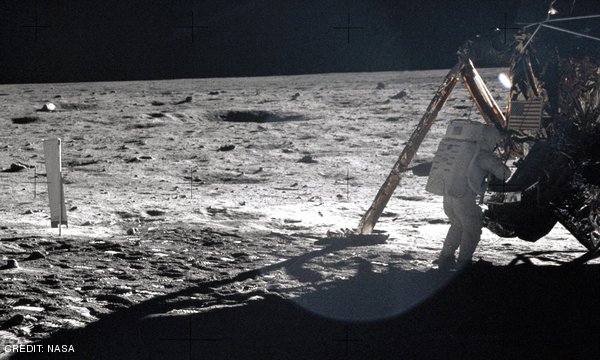

Neil Armstrong, the first person to walk on the Moon, died on the 25th of August. Jodrell Bank recorded signals from Apollo 11's Eagle lander during its descent to the Moon in 1969, and were able to measure its velocity using the Doppler shift in the frequency of the signal. The graph, produced using a 50-foot radio dish, shows where Neil Armstrong took manual control before landing. His family suggest that people give him a wink in tribute the next time they look up at the Moon.

Palaeontologists have uncovered dinosaur footprints in the unlikely location of the grounds of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. In a place where futuristic spacecraft are now developed, two nodosaurs walked 110 million years ago, and they may have been a mother and baby.

Show Credits

| News: | Stuart Harper |

| Interview: | Dr Simon Green and Libby Jones |

| Interview: | Dr Joseph Mottram and Libby Jones |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and John Field |

| Presenters: | Libby Jones and Mark Purver |

| Editors: | Mark Purver, Claire Bretherton, Liz Guzman and Christina Smith |

| Segment Voice: | Cormac Purcell |

| Website: | Mark Purver and Stuart Lowe |

| Producer: | Mark Purver |

| Cover art: | Neil Armstrong, photographed on the surface of the Moon by Buzz Aldrin. CREDIT: NASA |

[an error occurred while processing this directive]