In the show this time, we find out about Ian Morison's trip to observe the transit of Venus, Dr Paolo Padovani tells us about active galactic nuclei and we talk to Jakub Bochinski about exoplanets. Stuart rounds up the latest astronomy news and we find out what's in the July night sky from Ian Morison and John Field.

The News

In the news this month:

The Sun generates powerful stellar winds which launch jets of ionised material, known as plasma, out through the solar system. On Earth, the effects of these winds manifest as the auroras, ghostly emerald waves that are seen above polar skies. However these winds will continue to travel much further - travelling at speeds far exceeding 1,000,000 km/hour - blowing out a bubble in the surrounding interstellar medium called the Heliosphere. Its boundary, called the Heliopause, marks the point through which neither the Sun's plasma can escape or the surrounding interstellar plasma can penetrate. It is at this boundary that the Sun's domain ends and the powerful winds of other stars and supernovae take over. Currently it lies somewhere beyond 121 AU which is the current distance of the Voyager 1 space probe, the most distant man-made object.

It is what happens outside the Heliopause that is under debate due to new results from NASA's Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX). Previously it was expected that outside the Heliopause the supersonic winds from the interstellar medium collide with the solar winds as the Sun orbits the Galaxy. This results in a great arch forming around the Sun in the direction it is moving, much like the waves formed around the bow of a ship as it cuts through the water. This phenomenon is referred to as the bow shock. Unfortunately IBEX has found that this cannot be the case since measurements of neutrally charged atoms that can pass through the Heliosphere and into the inner solar system suggest that the overall speed of the interstellar winds are much too slow to be able to form the bow shock. The interpretation of the IBEX result is that the Sun is in fact moving much more slowly through the interstellar medium than previously thought. This leaves an open question as to how the environment beyond the Heliopause behaves. Although there are expectations for what will be discovered, perhaps the ultimate answer will not be obtained until the Voyager 1 space probe finally passes the boundary into truly interstellar space.

The Milky Way has three main components which it can be split into. The disk, where most star formation within the Galaxy occurs and our own Sun resides, the bulge which is a spherical orb packed densely with many old stars residing at the center of the Galaxy and finally this is all contained within a halo, a region of very sparsely populated space containing very old stars and globular clusters. To be able to determine the history of all these Milky Way features requires the precise dating of the stars which they contain. Unfortunately the techniques that are currently known can only obtain the ages of stars to within an accuracy of about of 1 to 2 billion years.

A new technique for determining the age of a population of stars has been proposed by Dr Jason Kalirai from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. The method involves observing the burning cinders of extinguished stars of 1 to 8 solar masses, these remnants are called white dwarfs. Kalirai's method involves observing only the very recently formed white dwarfs and then by estimating the white dwarf's mass he can determine the age of the progenitor star. This can be done since the mass of the white dwarf, the mass of the parent star and the age of the parent star are all related.

The dating technique by Kalirai allows for stellar populations to be dated to an accuracy of less than a billion years. This could allow for a greater distinction to be made between the stars contained within the Milky Way's halo. It is expected that stars within the halo were formed by mergers with dwarf galaxies early in the history of the Milky Way. However it is thought that there will be a difference in ages between the inner halo stars which are closer to the Galactic center than stars further away in the outer halo. This is because it is expected that stars in the outer halo blew away all the gas after a single burst of star formation meaning all the stars within the outer halo will be all from a similar early period in the history of the Galaxy. All that is required now is for Kalirai's method to be applied to many more white dwarfs so that the measurements of the ages within the inner and outer halos becomes statistically significant.

And finally: the atmosphere of Mars, the Earth's nearest neighbouring planet after Venus, is known to contain considerable quantities of methane gas. Interestingly, this gas is also dependent on the seasons on Mars, with Martian summer having considerable amounts of methane present in the atmosphere and Martian winters having little or no methane present. The origin of the methane gas is currently not well understood and there are many theories which have been proposed as an explanation, from geological processes to life on Mars. Unfortunately it is expected that neither life nor geology could produce the large quantities of methane that is observed by themselves or explain the seasonal dependence.

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute have suggested that there is another method for which methane can be produced in large quantities on Mars, a way which was previously overlooked due to the expected contribution being extremely small. In the laboratory they have exposed fragments of the Murchison meteorite, which is a carbonaceous meteorite that landed in Australia in 1969, to a simulated Martian atmosphere. The difference between the Martian and Earth atmospheres are quite dramatic, with temperatures dropping below -120C at night, air which is mostly composed of carbon dioxide and most critically for the Max Planck researchers is that it is exposed to extremely energetic ultra-violet radiation from the Sun. It was found that upon exposing ground-up fragments of the Murchison meteorite to similar levels of ultra-violet radiation as found on the Martian surface, a large quantity of methane was released from its internal structure. Since the Murchison meteorite is expected to be representative of most carbonaceous meteors within our solar system, it is expected that much of the surface of Mars could be littered with many tiny fragments of these meteors. These meteors would be exposed to different levels of the Sun's ultra-violet rays depending on the Martian season and emit significant quantities of methane. Of course the researchers at the Max Planck Institute do point out that even this significant contribution of methane to the atmosphere on Mars is not enough to explain all of it, meaning that other sources, including life, could still be needed.

Interview with Ian Morison

Our own night sky expert, Ian Morison, followed in the footsteps of Captain Cook by observing a transit of Venus at Astronomer's Point in the Dusky Sound fjord of New Zealand on the 6th of June. In this interview, he tells us about his voyage and how he attempted to measure the astronomical unit by combining his transit timings with those of a fellow observer in Alaska. He also explains why a Venus transit is a special event, and talks about historical attempts to measure the distance from the Earth to the Sun such as that by radar observations of Venus from Jodrell Bank Observatory.

Interview with Dr Paolo Padovani

Liz talked to Dr. Paolo Padovani from the ESO headquarters in Munich, Germany about radio-quiet and radio-load active galactic nuclei (AGNs). He explained to us the different components of the AGNs and how they are observed and classified, depending on their radio, optical and x-ray emission. He also talked about the ELT (Extremely Large Telescope) and what can we detect with it.

Interview with Jakub Bochinski

Jakub Bochinski from the Open University, tells us about observing exoplanets with the PIRATE observatory. PIRATE (Physics Innovations Robotic Astronomical Telescope Explorer) is a semi-robotic telescope in Majorica which can be controlled by astronomers using their mobile phones. Jakub goes on to tell us about the SuperWASP telescope and its search for exoplanets using the transit method, where the exoplanet passes in front of the parent star causing a dip in the light observed from the star. Jakub also mentions the number of planets currently discovered by Kepler and Superwasp and for the most current planet discoveries, click here: Kepler and SuperWASP.

The Night Sky

Northern Hemisphere

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the northern hemisphere night sky during July 2012.

Leo, containing the planet Mars, and Virgo, hosting Saturn, are setting in the west as darkness falls at the beginning of the month. The bright star Arcturus, in Boötes, is higher in the north-west. To its left is the circlet of stars called Corona Borealis, the Northern Crown. The Keystone asterism, in Hercules, is further up and left. Two-thirds of the way up the right-hand side of this trapezium of four stars, binoculars allow you to see the fuzzy glow of the globular cluster M13, the biggest and brightest in the northern hemisphere sky. Further over still is the Summer Triangle of the stars Vega in Lyra, Deneb in Cygnus and Altair in Aquila. Moving up from Altair towards Vega with binoculars, you reach a dark area called the Cygnus Rift, which contains cosmic dust that obscures part of the Milky Way. The asterism Brocchi's Cluster, or the Coathanger, is within this region. The small constellation of Delphinus, the Dolphin, is to the left of Altair.

The Planets

- Jupiter is a pre-dawn object, rising in the east-north-east about two hours before the Sun at the beginning of the month. It lies in Taurus and is between the Hyades and Pleiades Clusters on the 1st, as well as being close to Venus. It has a magnitude of -2.1 and an angular size of 35", and appears to get larger during the month. Saturn is nearing the end of its current apparition, and is seen low in the west after sunset at magnitude +0.7. It is 5° north of the first-magnitude star Spica in Virgo. Its disc is 17" across, while its rings are inclined at 13.5° to the line of sight. It will appear 90° around the horizon from the Sun on the 15th, allowing the shadow of the disc to be seen on the rings.

- Mercury can be seen shortly after sunset for the first few days of the month, and reaches greatest elongation (when it is furthest from the Sun in the sky) on the 1st. However, it can only be seen at around 5° elevation in the west-north-west, and binoculars will probably be needed to pick it out in the bright sky just after sunset (don't use these until the Sun has gone down). It reaches inferior conjunction (between the Earth and the Sun) on the 28th, and will reappear in the pre-dawn sky next month.

- Mars moves eastwards through Virgo as the month progresses, and its magnitude fades from +0.9 to +1 during the month. It is only 17° above the west-south-western horizon as darkness falls at the beginning of the month, and just 6° above by the end. Its angular size drops to 6" by the end of the month, so its surface features cannot easily be observed.

- Venus rises about an hour before sunrise at the beginning of the month, showing a crescent phase. It appears close to the star Aldebaran, within the Hyades Cluster in Taurus. Its angular size drops from 42 to 31" over the month, but its illuminated fraction increases so that its brightness remains around -4.5 in magnitude.

Highlights

- Noctilucent clouds may be seen in early July. These high clouds appear as blue wisps above the northern horizon from after sunset until around midnight. They are water vapour dissociated from methane around 80 kilometres up in the atmosphere, and are illuminated by the Sun after it has dropped below the horizon for observers on the ground.

- Venus and Jupiter appear close together in the pre-dawn sky during the first few days of the month, between the Hyades and Pleiades Clusters. Venus is 1° away from the star Aldebaran on the 7th.

- Before dawn on the 15th, Jupiter is occulted (blocked from view) by the Moon for observers in the south-east of the UK. The crescent Moon and Jupiter are above the Hyades Cluster at this time. The occultation begins with the disappearance of two of Jupiter's moons, Europa and Io, at around 02:48 BST (British Summer Time, one hour ahead of Universal Time). Jupiter follows suit, with two more of its moons, Ganymede and Callisto, being occulted just afterwards. The planet is invisible for around 3 minutes, reappearing around 03:09.

- Saturn and Mars are just 8° apart around the end of the month, although they are not very high in the sky. Mars will pass between Saturn and the star Spica in the middle of next month, but this will be difficult to observe due to its low elevation.

Southern Hemisphere

John Field from the Carter Observatory in New Zealand speaks about the southern hemisphere night sky during July 2012.

New Zealand now contains a newly recognised dark sky area, the Mackenzie Starlight Reserve. From this area, which contains the Mount John Observatory, faint phenomena such as the zodiacal light can be observed.

The brightest region of the Milky Way, between Scorpius and Sagittarius, is in the south-east after sunset. It is rich in bright star clusters and nebulae, even though much of it is obscured by interstellar dust. The Milky Way, as we see it in the sky, consists of two spiral arms: the Perseus Arm, away from the galactic centre in the west, and the Sagittarius Arm, towards the galactic centre in the east. Many of the stars which appear away from the Milky Way are part of the Orion-Cygnus Arm, in which our Solar System resides. Crux, the Southern Cross, sits atop the Milky Way. Appearing as a kite shape, to the Māori of Aotearoa (New Zealand) it is Te Punga, the Anchor. To one side is the dark and dusty Coalsack Nebula, while moving east along the Milky Way brings you to the stars Alpha and Beta Centauri in Centaurus, the Centaur. Lupus, the Wolf, is in front of it. Its two brightest stars are the blue giants Alpha and Beta Lupi, and near to the latter is the remnant of a supernova observed in the year 1006. A medium-sized telescope shows the open globular clusters NGC 5824 and NGC 5986 and the open clusters NGC 5822 and NGC 5749 in Lupus.

The Planets

- Mars is fading as it moves away from the Earth, but is still visible and is reddish-orange in colour, passing from Leo into Virgo during the month.

- Saturn is in Virgo, looking yellow near the bright blue star Spica. A small telescope reveals its rings and its largest moon, Titan, while a slightly larger telescope will show more moons.

- Mercury appears on the north-western horizon just after sunset, looking orange and with changing phases which can be seen through a telescope.

- Venus and Jupiter are close together in the morning sky. A telescope allows Jupiter's four largest moons and its surface bands of cloud to be seen. Following a line from Venus through Jupiter, you reach the Pleaides Cluster, known to Māori as Matariki or Little Eyes.

Odds and Ends

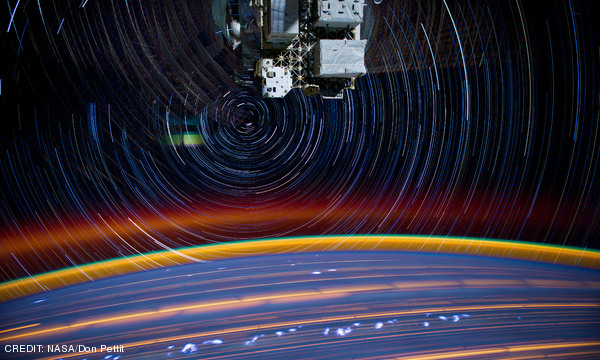

NASA astronaut Don Pettit has taken some amazing star trail images from the International Space Station.

The Royal Society Summer Science Exhibition is taking place in London between the 3rd and 8th of July and includes astronomy stands about ALMA, Herschel and cosmic rays.

The NuSTAR X-ray telescope was successfully launched on the 13th of June. The "first light" image was released on the 28th of June and shows the bright X-ray source Cygnus-X1.

Show Credits

| News: | Stuart Harper |

| Interview: | Ian Morison and Mark Purver |

| Interview: | Dr Paolo Padovani and Liz Guzman |

| Interview: | Jakub Bochinski and Libby Jones |

| Night sky: | Ian Morison and John Field |

| Presenters: | Megan Argo, David Ault and Jen Gupta |

| Editors: | Jen Gupta, Claire Bretherton, Liz Guzman, Mark Purver and Christina Smith |

| Segment Voice: | Cormac Purcell |

| Website: | Christina Smith and Stuart Lowe |

| Producers: | Libby Jones, Christina Smith and Jen Gupta |

| Cover art: | A composite star trail image taken from the International Space Station. CREDIT: NASA/Don Pettit |

[an error occurred while processing this directive]