We started the show with a reminder about Jodcast Live on 21st November at 1pm. If you haven't already booked a place, let us know as soon as possible. In the show we have an interview with Robert Laing about interferometers and ALMA, and we talked to Willem Baan about interference in radio astronomy. As ever we have the latest astronomical news, what you can see in the October night sky, and your feedback.

The News

In the news this month:

- Using various techniques, astronomers have, over the last decade, discovered many hundreds of planets outside our own solar system. Most of these techniques are indirect because planets are much fainter than the stars they orbit, and so are very hard to detect directly. Because their effects are easier to spot, larger planets are easier to find, but smaller and smaller planets are being discovered as techniques and technology improve. One of the smallest exoplanets known to date is CoRoT-7b, a planet discovered by the CoRoT satellite in February 2009, orbiting an otherwise unremarkable 11th magnitude star catalogued as TYC 4799-1733-1, located almost 500 light years away in the constellation of Monoceros (pronounced: manoceras). Most of the known exoplanets are thought to be larger versions of Jupiter, likely to be large gas giants, but new observations of CoRoT-7b suggest that it is far more like our own Earth. A team of astronomers, led by Didier Queloz at the Geneva Observatory in Switzerland, used the HARPS instrument on ESO's 3.6-metre telescope at the La Silla observatory in Chile, to observe the CoRoT-7 system and try and determine the mass of CoRoT-7b. HARPS, or the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher, is a high resolution spectrograph which enables astronomers to measure the tiny changes in velocity of a star as it is gently tugged by the gravitational pull of it's orbiting planets. These velocity shifts are extremely small, so very accurate spectrographs are needed to see the effects. In the case of CoRoT-7b, the planet is so close to its parent star that it completes one orbit every 20.4 hours, blocking out a tiny fraction of the stars' light for just one hour during each orbit. Because the planet is so small, the team had to obtain more than 70 hours of observations to see the tiny changes in the stars' spectrum that would tell them about the planet. What the team found was that CoRoT-7b is one of the lightest exoplanets known, with a mass of just 4.8 times that of the Earth, putting it in the category of so-called "super-Earths". Since the planet directly transits the star, passing directly between the star and us, astronomers have already been able to determine that the planet's radius is less than twice that of Earth. If you know both the mass and the radius of a planet, you can calculate its density. The team did this and found that CoRoT-7b has a density of 5.5 grams per cubic centimetre, very similar to the density of the Earth. This suggests that CoRoT-7b is a rocky planet, not a gas giant like Jupiter, and is likely to be composed mainly of silicates with a small iron core, the first time such a determination has been made for such a small exoplanet. As well as determining the mass and density of CoRoT-7b, the team also discovered a new planet, CoRoT-7c, which is slightly larger with a mass of 8.4 times that of Earth. Unfortunately, this planet does not directly transit the star, so its radius, and hence density, cannot be determined. The research will be published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics on October 22nd.

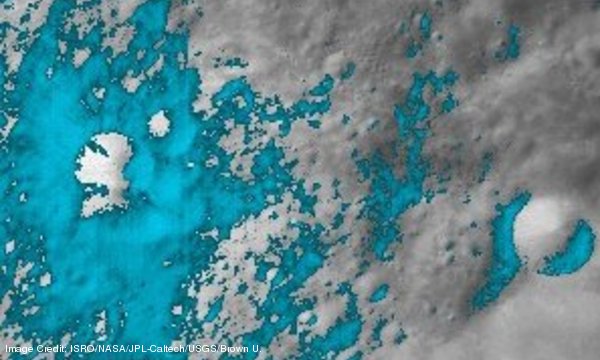

- Hydroxyl on the Moon. It is thought that the Moon was formed about four and a half billion years ago by the collision of a Mars-sized object with the Earth. The heat from the impact and subsequent accretion of material created a magma ocean which would have caused the loss of most of the volatile materials from the surface, so-called because they have low boiling points and evaporate easily. In a press conference at NASA on Thursday 24th September, results were announced from three separate spacecraft showing evidence of water on the lunar surface in far greater quantities than has previously been seen. Two of these spacecraft, Cassini and Deep Impact, observed the Moon as they passed by on their way to other parts of the solar system while the third, India Space Research Organisation's Chandrayaan-1, observed the lunar surface from orbit around the Moon. What each of these probes detected was an absorption feature in the infra-red part of the spectrum at a wavelength of about 3 microns, a wavelength characteristic of absorption by hydroxyl - a hydrogen atom joined together with an oxygen atom. Add another hydrogen to hydroxyl and you produce H20, water, which also absorbs infra-red light near 3-microns.

It has been known since the observations of the Lunar Prospector spacecraft in the late 1990s that there is an estimated 10 to 300 million metric tones of water ice buried in permanently shadowed craters at the lunar poles. These new results however, show that the hydroxyl and water signature is in fact present over large parts of the lunar surface, not just at the poles.

Launched on October 22nd 2008, India's Chandrayaan-1 carried several scientific instruments on board. One of these was the Moon Mineralogy Mapper, or M3, built by NASA, a spectrograph operating in the infra-red part of the spectrum. Although Chandrayaan-1 sadly ceased operations last month, it had already returned many months of usable data from the instruments on board. When the data from the M3 experiment was analysed, researchers found absorption features consistent with patterns expected for water and hydroxyl over most of the lunar surface. Although M3 only probed the top few millimetres of the lunar regolith, they found a strong hydroxyl signature across the surface, stronger towards the lunar poles at higher latitudes, and varying throughout the lunar cycle, suggesting that the Sun has some effect on the distribution. According to the scientists, the most likely origin for this water is a reaction between protons in the solar wind and oxygen atoms already present in the lunar dirt. The M3 results were subsequently confirmed by observations by the Deep Impact spacecraft which also has instruments that observe in the infra-red and regularly uses observations of the Moon for calibration purposes, and also in old data from the Cassini spacecraft which observed the Moon during a flyby in 1999. The data show that there may be as much as 0.1 to 1 per cent water by weight in the regolith, in contrast to the rocks brought back by the Apollo missions which were incredibly dry. This is roughly equivalent to a litre of water per cubic metre of regolith but, since it is only present in the top few millimetres of soil, extracting usable amounts of water would require processing a very large surface area.

The results from the three spacecraft were announced together to coincide with the publication of three papers in the journal Science on September 24th, and come just two weeks before another spacecraft, NASA's LCROSS, the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, is due to crash into the Moon's surface near the south pole in an attempt to kick up water ice buried in the regolith in craters which rarely see sunlight. - Edwin Hubble's original classification of galaxies into various types based on their visible shapes and structures has been a feature of extra-galactic astronomy since the 1920s. The scheme, originally thought to depict an evolutionary sequence, has two major groups: spiral galaxies with a small central bulge, spiral arms and possibly a central bar, and elliptical galaxies that are more spherical in structure with no spiral arms or disk. There are however, many galaxies which do not fit into this scheme, being neither spherical or disk-like, and these are usually lumped together into a class called the irregulars. These disturbed galaxies are surprisingly common, and many are the result of collisions or close encounters between galaxies. Such interactions happened frequently throughout the history of the universe, but it is also going on right now in our own galactic neighbourhood. The nearest major galaxy to our own is the Andromeda Galaxy, otherwise known as M31, slightly larger than the Milky Way and located 2.5 million light years away. It is heading towards the Milky Way at some 300 km/s and, in a few billion years, the two galaxies will eventually collide. In some cosmological models, galaxies grow over time by disrupting and absorbing smaller galaxies in such collisions. In such violent processes, a significant number of stars should be tossed out of the galaxies involved, forming a diffuse halo which can provide clues to the merger history of a galaxy, if they are bright enough to be detected.

In research reported in the journal Nature on the 3rd of September, a team of astronomers led by Alan McConnachie at the Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics in Canada, report a panoramic survey of Andromeda and its nearby neighbour, the Triangulum galaxy, M33, which shows clear evidence of the remnants of galactic mergers. Detecting this evidence is difficult as these stellar populations are extremely faint and distributed over a huge area, so the astronomers are using the MegaCam camera on the 3.6-metre Canada-France-Hawaii telescope to build up a sensitive wide-field survey of the Andromeda galaxy and it's companions. The so-called Pan-Andromeda Archaeological Survey will cover more than 300 square degrees when completed in 2011, but has already produced results showing the vast extent of M31's stellar halo, covering an area of nearly 100 times the classical optical disk of the galaxy. These early results from the survey lend support to the idea that large galaxies build up through the accretion of smaller galaxies. The halo stars discovered away from the disk of M31 are unlikely to have been formed at their present positions because there is not enough gas there for star formation to occur. The most likely explanation is that they have been thrown out in a tidal interaction. Another piece of evidence that they are relics from previous galactic mergers is that the stars in this faint population are often located in huge arcs, loops and other diffuse structures which are characteristic of the gravitational disruption of dwarf galaxies undergoing a merger with a larger galaxy. As well as lending support to the hierarchical model of galaxy formation, the team's results also show a new diffuse stellar structure around M33, M31's largest companion galaxy. This newly discovered feature matches up with a distortion in the disk of M33, as well as a mild warp seen in the outer disk of M31, adding to the evidence of a past tidal interaction between the two galaxies. - And finally... Launched on the 14th of May this year, the Planck spacecraft released the results of it's "first light" survey during September. Since its launch along with the Herschel telescope, Planck has been undergoing testing, commissioning and calibration of its instruments, making its first observations on the 13th of August. Designed to detect the cosmic microwave background, the relic radiation left over from the Big Bang, Planck has several survey instruments on board. In order to maximise their chances of detecting the tiny fluctuations in the temperature of the CMB, the sensitive detectors must be cooled down almost to absolute zero, a temperature of minus 273 Kelvin. Starting on August 13th, the satellite began a first light survey to verify the stability and calibration of the instruments. The survey lasted two weeks during which Planck continuously surveyed the sky, scanning a strip 15 degrees wide. Following the completion of this test observation, routine operations began on August the 27th. Full-time operations will continue for the next 15 months, with the first all-sky map expected to be assembled after approximately six months.

Interferometry

Jen and Roy interviewed Robert Laing (ESO) about radio interferometry and the new instruments coming online soon including ALMA in Chile.

Interference

Jen and Roy interviewed Willem Baan (ASTRON) about radio interference and protecting the radio bands.

The Night Sky

Ian Morison tells us what we can see in the night sky during October 2009.

Northern Hemisphere

During the mid-evening in October, fairly high in the south is Pegasus, the Winged Horse. The top left-hand star of the square of Pegasus is the star Alpha Andromedae from which you can find the Andromeda Galaxy, M31. Between Cassiopeia and Perseus is a rather lovely region of sky containing the Double Cluster which is very nice in binoculars and even better in a small telescope. Perseus also contains the star Algol which is an eclipsing binary which changes its brightness every few days or so. Below Pegasus is the head of one of the fish in Pisces and just below that is the planet Uranus. Down to the left of Pisces is Cetus the whale and to the right is Aquarius. Up to the right of Pegasus are the constellations of Cygus the Swan, Lyra the Lyre and Aquila the Eagle with their bright stars making up the Summer Triangle. Just down to the left of Cygnus is the tiny constellation of Delphinus, The Dolphin.

The Planets

- Jupiter is in Capricornus and dominates the south-eastern part of the sky in the evening. With a small telescope you can easily make out the equatorial bands and spot the moons. On the 26th October it will be just to the lower right of the Moon.

- Saturn re-appears in the pre-dawn sky during October and gets better towards the end of the month. It rises at about 4 am UT. A small telescope will easily show Saturn's largest moon Titan.

- Mercury reaches western elongation on October 6th. It is the most favourable dawn apparition this year.

- Mars rises about 10.30 UT in the middle of the month. It is in Gemini at the start of October but moves into Cancer around the 12th October. It's due south at about 6.30 UT in the middle of the month.

- Venus can be seen low in the east rising a couple of hours before sunrise.

Highlights

- On 7th October a gibbous Moon passes below the Pleiades cluster.

- On 10th October at 9:44 BST there is an eclipse of Jupiter's moon Europa by Io. On 16th October Ganymede will eclipse Europa at 10:10 BST.

- On October 10th Venus, Saturn and Mercury make a nice line in the sky. By the 16th October they will have separated somewhat but will be joined by the waning crescent Moon.

- A good time to look for Uranus is around 18th October around New Moon. Under perfect skies you might spot it with the naked eye.

- Around October 21st the Orionids will be best seen in the hours after midnight.

Southern Hemisphere

Towards the north you can see Cygnus low above the horizon with Lyra to the north west. Over in the north-eastern sky is Pegasus. The circlet of Pisces is well visible so a good chance of finding Uranus. Higher up towards the zenith is the wonderful constellation of Sagittarius. Looking south you've got the Milky Way stretching from the south over towards the south west. East of south you can see the Large Magellanic Cloud. Just to the lower right is the lovely region named the Tarantula Nebula. Looking up towards the zenith from the LMC is the Small Magellanic Cloud with nearby globular cluster 47 Tucanae. Fairly low in the south west is Centaurus A.

Odds and Ends

The upcoming MoonWatch will be on the 24th October - 1st November and follows the international event named Galilean Nights.

NASA's LCROSS is due to impact the Moon on October 9th at 12:30 pm BST/7:30 am EDT/4:30 am PDT. It will impact the crater Cabeus. The Moon will be very low as seen from the UK so it isn't best positioned but you might see something with a telescope. Warning: make sure that you don't point binoculars or a telescope at the Sun.

In the forum, Stella did some research on the object near the ISS mentioned in Ask an Astronomer and Jodatheoak has a picture they took of the ISS passing overhead on Flickr.

On Twitter we were sent a DM saying "Please instruct your readers that there is no such element as ALU-MIN-KNEE-UM. It makes you sound ignorant. I still like JodCast." Of course, in Britain we do pronounce it that way because we spell it differently to the US. According to wikipedia "The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) adopted aluminium as the standard international name for the element in 1990, but three years later recognized aluminum as an acceptable variant...IUPAC officially prefers the use of aluminium in its internal publications". Thanks to @Knusper2000 for pointing out that the new instrument on Hubble is called wide field camera 3 not wide field planetary camera 3.

Show Credits

| News: | Megan Argo |

| Noticias en Español - Octubre 2009: | Lizette Ramirez |

| Interview: | Robert Laing, Roy Smits and Jen Gupta |

| Interview: | Willem Baan, Roy Smits and Jen Gupta |

| Night sky this month: | Ian Morison |

| Presenters: | David Ault, Jen Gupta and Stuart Lowe |

| Editor: | Sarah Bryan, Adam Avison and Stuart Lowe |

| Intro: | David Ault |

| Lord Dracula: | Bruce Busby |

| Jennifer Harker: | Helen Cashin |

| Segment voice: | Danny Wong-McSweeney |

| Website: | Stuart Lowe |

| Cover art: | Water seen on the Moon by the Moon Mineralogy Mapper onboard India's Chandrayaan-1 Credit: ISRO/NASA/JPL-Caltech/USGS/Brown U. |

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

Noticias en Español - Octubre 2009 [Duration 13:32]:

Noticias en Español - Octubre 2009 [Duration 13:32]: